Gallery Tour

Schöneberg

by Kito Nedo, 2023

English Version

Monia Ben Hamouda (b. 1991, Milan, Italy) makes letters dance at ChertLüdde. In the exhibition About Telepathy and other Violences, the Italian-Tunisian artist shows, among other things, floating steel lettering that transforms into images depending on the viewer’s perspective. Ben Hamouda “marinates” her calligraphic-looking sculptures with chili, cumin, curry, turmeric and cinnamon as she considers spices to be “extremely rich and iconic material.” Thus, the artist extends her installation into the realm of the olfactory. In a parallel exhibition titled Handmade Militancy, we see works by Milanese artist Clemen Parrocchetti (1923-2016) that have rarely before been shown. Parrocchetti produced feminist assemblages using conventional housework materials such as sewing kits, cooking utensils, medicines and textiles.

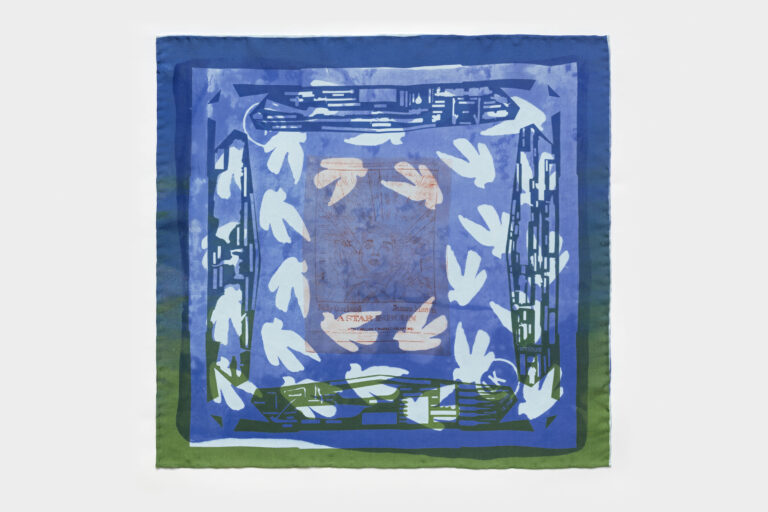

In Josefine Reisch’s new paintings, supposedly contradictory spheres are united. At Galerie Noah Klink, the painter, who was born in Berlin in 1987, brings together royal, pop-cultural, capitalist and socialist symbols under the title Dowry. A contradictory and at the same time visually attractive amalgam of images unfolds. The juxtaposition of populism, consumerism, royalism, and history suddenly becomes vivid. Is this our present? Valuable damask fabrics, which have been traditionally produced in southern Saxony for centuries and relatively untouched by social changes, serve as image carriers for the painter.

The New York artist Jordan Strafer, born in Miami in 1990 as the daughter of two criminal defense attorneys, works primarily with video. Her installations mix fictional and empirical references. “I guess I incorporate fragments from my past into my work in order to come to terms with them,” says Strafer. “I work very intuitively, often mixing media references with autobiographical elements.” In her Berlin exhibition, titled Holding, Strafer references both the 1962 French film The Trial of Joan of Arc, directed by Robert Bresson, and the so-called “troubled teen industry” in the United States. Inside Heidi gallery’s space, Joan of Arc’s inquisition dungeon is transformed into a typical interior of a US juvenile detention center.

Distant galaxies, planets and dark matter: Björn Dahlem (b. 1974, Munich, Germany) usually draws inspiration from astronomical and cosmological research. Something Secret about the Universe (I always wanted to tell you) at Galerie Guido W. Baudach alludes to scientific rhetoric while sounding like something Neil deGrasse Tyson and Woody Allen might say if merged together. The title suits the artist’s sense of humor who produces his meticulous installations, sculptures and objects using decidedly simple materials. In the gallery, Dahlem constructed a comprehensive spatial installation in which new sculptures are embedded.

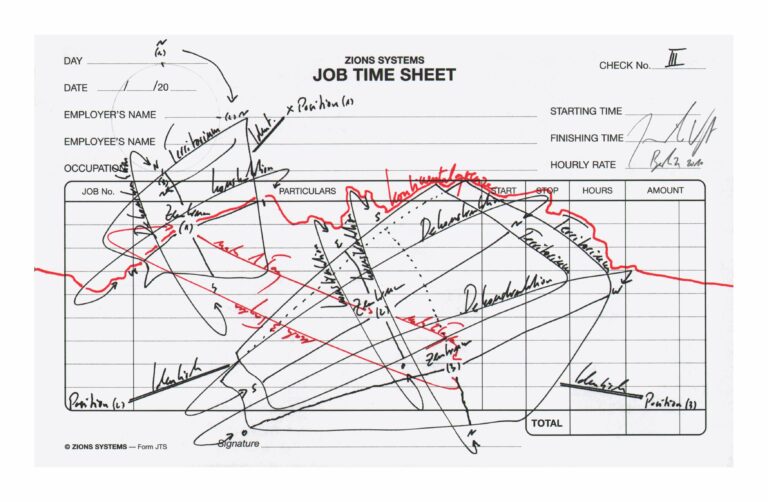

In the oeuvre of Berlin-based Jorinde Voigt, (b. 1977, Frankfurt am Main, Germany) the boundaries between writing and recording are fluid. “I come more from notation,” the artist once explained. Notation is the recording of music in musical notation. In Voigt’s case, it’s more a matter of an extended drawing practice that allows her to produce poetic images with the help of graphic inscription of fleeting movements, currents and sounds. The show “Trade Area” at Klosterfelde Edition focuses on original studies from the years 2005-2010. Predominantly created with ink and pencil on graph paper, these drawings are shown for the first time as a coherent series.

Everything from glass to quartz sand to sisal fibers can turn into artistic material in the hands of Kapwani Kiwanga, who is showing her work at Tanja Wagner Gallery. Whenever a material is connected to a “historical, political and geological history,” it instantly becomes interesting for the Canadian artist who will take over the Canadian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2024. The sand, for example, with which Kiwanga fills her minimalist glass sculptures, is indeed a political material: on the one hand, a coveted natural resource for various industries and, at the same time, the main telltale sign for drought—an enduring theme of our present in the wake of climate crisis.

Contemporary Cave Art is what Hito Steyerl, who’s repeatedly participated in numerous documenta iterations, has called her exhibition at Esther Schipper. In a dim, cave-like space with artificially illuminated plant spheres and video projections, the artist examines the post-pandemic conditions of cultural production as well as the NFT and crypto boom. Another central topic of discussion is how biological knowledge and fermentation processes can inspire systems of decentralization and autonomy. In parallel, Sun Yitian (b. 1991, China) is exhibiting three new paintings depicting large-scale impressions of doll heads. These strangely captivating still lifes perpetuate the tradition of artistic engagement with consumer culture.

Across the street at HUA International, we find Hollow Garden by Chen Dandizi. The first solo exhibition in Europe by the Chinese artist who was born in 1990 in Hezhou in southern China and initially studied oil painting at the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts. Today, the artist works primarily with video, installation, photography and literature. Part of the exhibition is a three-channel video installation titled Sixty Seconds in Wonderland Park which observes the artificial wilderness of a lush city park in southern China and the romantic wafts of mist forming around a manmade pond every afternoon.

The self-portraits of Lydia Pettit shown at Judin appear stern and unsparing. Ruthlessness is at the core of their concept. “I try not to portray myself as anyone other than who I am,” says the US painter, who was born in 1991 in Maryland, northwest of Washington, and now lives in London. “I make a conscious effort not to be sexy or attractive to the viewer in a conventional sense.” Nowadays, when many people use filters or plastic surgery to emulate a kind of “Instagram face,” Pettit’s insistence on realism is a radical gesture.

Diamond Stingily (b. 1990) works as a sculptor, installation artist and poet. Last year, she starred in the acclaimed US art-school satire The African Desperate. Stingily’s installations pack a punch. In 2014, while preparing to say goodbye to her hometown and move to New York, she staged one of her early exhibitions in her native Chicago as a funeral—complete with obituary, Bible citations and floral arrangements. Her installation Entryways (2021), in turn, consisted of old doors and baseball bats, making reference to experiences of violence in the everyday lives of many people. “It’s a privilege not to live in violence,” says Stingily. Her works are often of an autobiographical nature, but at the same time they always comment on shared experiences. I’m not coming back here is Stingily’s new installation at Isabella Bortolozzi.

The art of Aziz Hazara revolves around the traces of war, violence and oppression. Born in 1992 in the Afghan province of Wardak, Hazara studied between 2013 and 2017 in Lahore, Pakistan. Between 2021 and 2022, he lived and worked as artist-in-residence at Berlin’s Künstlerhaus Bethanien. During that time, he created, among other things, his large-scale photo installation I am looking for you like a drone, my love which is now on view at PSM. This piece examines the vast amounts of discarded material, including electronic scrap, military equipment and other waste, that NATO troops left behind after their hasty withdrawal from Bagram Air Base outside of Kabul. Hazara speaks of a contaminated “landscape of leftovers” around which newfound logistics and economies have formed.

At Galerie Barbara Wien, Michael Rakowitz is showing an ambiguous homage to the Canadian poet and singer Leonard Cohen who died in Los Angeles in 2016 at the age of 82. A few years ago, Rakowitz bought a typewriter on ebay that once belonged to Cohen. On this device, the artist wrote a long letter addressed to the famed singer-songwriter in August 2015. A letter that has forever remained unanswered. In the note, Rakowitz asked the musician for permission to perform at a concert in Ramallah, Palestine, playing cover versions of Cohen’s songs. The background: in 2009, a Palestinian boycott prevented a Cohen concert in Ramallah because the musician wanted to also perform in Tel Aviv. “Leonard, I believe boycotts are problematic,” wrote Rakowitz. The artist’s Leonard Cohen research project I’m good at love, I’m good at hate, it’s in between I freeze, which has been running since 2009, is now on show in Berlin for the first time.

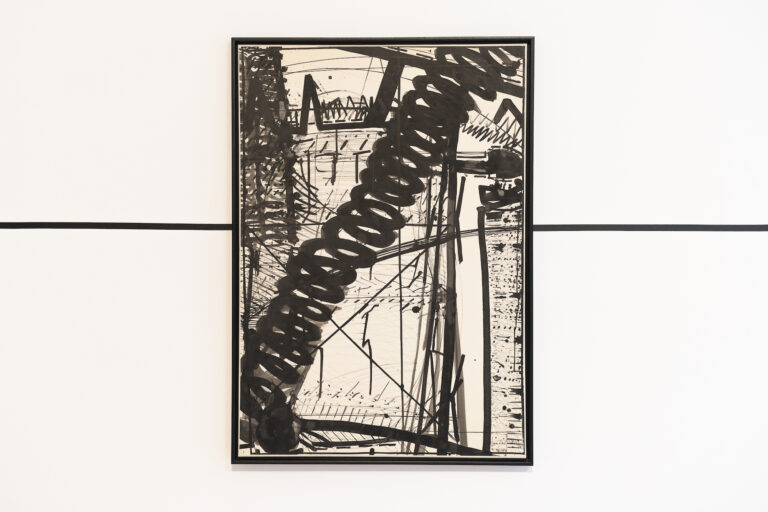

Be it window squeegees, windshield wipers or razor blades, the painter K.R.H. Sonderborg (1923-2008) was happy with any tool he could get his hands on to bring his wild, mostly black strokes, lines, swirls and color trajectories onto canvas or paper. Inspired by American Abstract Expressionism, East Asian calligraphy and French Tachisme, he became synonymous with informal painting and the “principle of the formless” in the 1950s. An aesthetic which was considered deeply controversial in the post-war era. Sonderborg seemed to like the image of the nomadic troublemaker: “I am a painter without a studio, always in a makeshift state. And I love that. For me, painting is almost a criminal act. I’m like someone who goes down to the basement to kill a rat.” With this exhibition, Georg Nothelfer Gallery celebrates the centenary of the painter’s birth.

Gallery Tour

Schöneberg

von Kito Nedo, 2023

Deutsche Version

Monia Ben Hamouda, geboren 1991 in Mailand, lässt bei ChertLüdde die Buchstaben tanzen. Unter dem Titel About Telepathy and other Violences zeigt die italienisch-tunesische Künstlerin unter anderem schwebende Schriftzüge aus Stahl, die sich je nach Betrachtung in Bilder verwandeln. Die kaligraphisch anmutenden Skulpturen präpariert Ben Hamouda mit Chili, Kreuzkümmel, Curry, Kurkuma oder Zimt. Gewürze sind für die Künstlerin „äußerst reichhaltiges und ikonisches Material“. Auf diese Weise erweitert Ben Hamouda ihre Installation in den Bereich des Olfaktorischen. In einer parallelen Ausstellung werden unter dem Titel Handmade Militancy bislang selten gezeigte Arbeiten der Mailänder Künstlerin Clemen Parrocchetti (1923–2016) präsentiert. Parrocchetti produzierte aus herkömmlichen Hausarbeits-Materialien wie Nähzeug, Kochutensilien, Medikamente, Textilien feministisch-kritische Assemblagen.

In den neuen Gemälden von Josefine Reisch finden sich vermeintlich gegensätzliche Sphären vereint. In der Galerie Noah Klink bringt die 1987 in Berlin geborene Malerin unter dem Titel Dowry (auf Deutsch „Mitgift“ oder „Aussteuer“) königliche, popkulturelle, kapitalistische und sozialistische Symbole zusammen. So entfaltet sich ein widersprüchliches und zugleich sehr attraktives Bild-Amalgam. Das Nebeneinander von Populismus, Konsumismus, Royalismus und Geschichte wird plötzlich anschaulich. Ist das unsere Gegenwart? Als Bildträger dienen der Malerin wertvolle Damaststoffe, die traditionell seit Jahrhunderten und relativ unbeeindruckt von gesellschaftlichen Veränderungen in Südsachsen hergestellt werden.

Die New Yorker Künstlerin Jordan Strafer, geboren 1990 in Miami als Tochter zweier Strafverteidiger:innen, arbeitet vorwiegend mit Video. In ihren Installationen mischen sich fiktionale und autobiografische Bezüge. „Ich baue wohl Teile aus meiner Vergangenheit in mein Werk ein, um sie zu bewältigen“ sagt Strafer. „Ich arbeite sehr intuitiv, häufig vermische ich Medienbezüge mit autobiografischen Elementen.” In ihrer Berliner Ausstellung mit dem Titel „Holding“ bezieht sich Strafer sowohl auf den französischen Film „Der Prozess der Jeanne d’Arc“ aus dem Jahre 1962, bei dem Robert Bresson die Regie führte, als auch die sogenannte „troubled teen industry“ in den USA. In der Galerie Heidi verwandelt sich der Inquisitionskerker der Jeanne d’Arc in ein typisches Interieur einer US-Jugendanstalt.

Ferne Galaxien, Planeten und Dunkle Materie: Der 1974 in München geborene Künstler Björn Dahlem lässt sich für seine Kunst meist von astronomischen und kosmologischen Forschungen inspirieren. Something Secret about the Universe (I always wanted to tell you)—der Titel der aktuellen Ausstellung in der Galerie Guido W. Baudach spielt auf wissenschaftliche Rhetorik an, klingt aber nach Neil deGrasse Tyson und Woody Allen. Das passt auch zum Humor des Künstlers, der seine präzisen Installationen, Skulpturen und Objekte meist aus betont einfachen Materialien produziert. In der Galerie errichtet Dahlem eine umfassende Rauminstallation, in welche verschiedene neue Skulpturen eingebettet sind.

Im Gesamtwerk der Berlinerin Jorinde Voigt sind die Grenzen zwischen Schreiben und Aufzeichnung fließend. „Ich komme eher von der Notation“ hat die 1977 in Frankfurt am Main geborene Künstlerin einmal erklärt. Notation ist das Aufzeichnen von Musik in Notenschrift. Im Fall von Voigt geht es eher um eine erweiterte zeichnerische Praxis, die es ihr erlaubt, mithilfe zeichnerischer Notierung von flüchtigen Bewegungen, Strömungen, Geräuschen poetische Bilder zu produzieren. Im Mittelpunkt der Schau Trade Area bei Klosterfelde Edition stehen Originalstudien aus den Jahren 2005–2010. Erstmals werden diese Zeichnungen, die von der Künstlerin überwiegend mit Tusche und Bleistift auf Millimeterpapier ausgeführt wurden, als zusammenhängende Werkgruppe gezeigt.

Von Glas über Quarzsand bis hin zu Sisalfasern kann alles zum künstlerischen Material von Kapwani Kiwanga werden, die in der Galerie Tanja Wagner ihre Kunst zeigt. Wenn ein Material auf eine „historische, politische und geologische Geschichte“ verweist, wird es interessant für die kanadische Künstlerin, die 2024 den kanadischen Pavillon auf der Venedig-Biennale bespielen wird. Der Sand zum Beispiel, mit dem Kiwanga ihre minimalistischen Glasskulpturen befüllt, ist ein politisches Material: einerseits begehrter Rohstoff für verschiedene Industrien und zugleich die zentrale Chiffre für Trockenheit, die im Zuge der Klimakrise das Dauerthema unserer Gegenwart ist.

Contemporary Cave Art hat die mehrmalige documenta-Teilnehmerin Hito Steyerl ihre Ausstellung bei Esther Schipper genannt. In einem schummrig-höhlenartigen Raum mit künstlich beleuchteten Pflanzenkugeln und Videoprojektionen werden die postpandemischen Bedingungen kultureller Produktion und der NFT- und Krypto-Boom verhandelt. Auch steht hier die Frage im Raum, wie biologisches Wissen und Fermentationsprozesse Systeme der Dezentralisierung und Autonomie inspirieren können. Parallel dazu werden in einer weiteren Präsentation drei neue Gemälde von Sun Yitian gezeigt. Die 1991 geborene chinesische Künstlerin malt großformatige Ansichten von Spielzeug-Puppenköpfen, die sie zuvor in Szene setzt und fotografiert. Das Ergebnis sind seltsam entrückte Stillleben, die die Geschichte der künstlerischen Auseinandersetzung mit der Konsumkultur fortschreiben.

Gegenüber wird bei HUA International Hollow Garden von Chen Dandizi gezeigt. Es ist die erste Einzelausstellung der chinesischen Künstlerin in Europa, die 1990 im südchinesischen Hezhou geboren wurde und zunächst Ölmalerei an der Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts studierte. Heute arbeitet die Künstlerin vorrangig mit Video, Installation, Fotografie und Literatur. Jetzt ist unter anderem die Dreikanal-Videoinstallation Sixty Seconds in Wonderland Park zu sehen, in der es um die künstliche Wildnis eines üppigen Stadtparks in Südchina und die romantischen Nebelschwaden geht, die dort jeden Nachmittag um einem künstlichen Teich entstehen.

Die bei Judin gezeigten Selbstportraits von Lydia Pettit wirken schonungslos. Und das ist Konzept. „Ich versuche, mich nicht als jemand anderes darzustellen als diejenige, die ich bin.“ sagt die US-amerikanische Malerin, die 1991 in Maryland, nordwestlich von Washington, geboren wurde und heute in London lebt. „Ich bemühe mich bewusst nicht darum, beispielsweise in diesem Sinne für die den Betrachter sexy oder attraktiv zu sein.“ In der Gegenwart, in der viele Menschen mit Filtern oder Operationen einer Art Schablonengesicht bzw. einem „Instagram Face“ nacheifern, ist Pettits Beharren auf Realismus eine radikale Geste.

Diamond Stingily, geboren 1990, arbeitet als Bildhauerin, Installationskünstlerin und Dichterin. Im vergangenen Jahr spielte die Hauptrolle in der gefeierten US-Art-School-Satire The African Desparate. Stingilys Installationen haben es in sich. Eine ihrer frühen Ausstellungen in ihrer Geburtsstadt Chicago inszenierte sie 2014 als Begräbnis, komplett mit Nachruf, Bibel und Blumenschmuck. Da war Sie gerade im Begriff, nach New York umzuziehen. Ihre Installation Entryways (2021) wiederum bestand aus alten Türen und je einem Baseballschläger und assoziierte Gewalterfahrungen im Alltag vieler Menschen. „Es ist ein Privileg, nicht in Gewalt zu leben“ sagt Stingily. Oft haben ihre Werke einen autobiografischen Bezug, verweisen zugleich aber auch auf gemeinschaftliche Erfahrungen. I’m not coming back here lautet der Titel von Stingilys neuer Installation in der Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi.

Um die Spuren von Krieg, Gewalt und Unterdrückung dreht sich die Kunst von Aziz Hazara. Aziz Hazara wurde 1992 in der afghanischen Provinz Wardak geboren und studierte zwischen 2013 und 2017 in Lahore, Pakistan. Zwischen 2021 und 2022 lebte und arbeitete er als Artist-in-Residence im Berliner Künstlerhaus Bethanien. In dieser Zeit entstand unter anderem seine groß angelegte Fotoinstallation I am looking for you like a drone, my love die jetzt bei PSM zu sehen ist. In der Arbeit geht es um die riesigen Mengen an weggeworfenem Material, darunter Elektronikschrott, Militärtechnik und andere Abfälle, welche die Nato-Truppen nach ihrem überstürzten Abzug vom Luftwaffenstützpunkt Bagram außerhalb von Kabul zurückließen. Hazara spricht von einer kontaminierten „Landschaft von Überresten“, um die herum sich eigene Logistiken und Ökonomien gebildet haben.

Eine zwiespältige Hommage an den kanadischen Dichter und Sänger Leonard Cohen, der 2016 im Alter von 82 Jahren in Los Angeles starb, präsentiert der US-Amerikaner Michael Rakowitz in der Galerie Barbara Wien. Auf ebay ersteigerte Rakowitz vor ein paar Jahren eine Schreibmaschine, die einst Cohen gehörte. Auf diesem Gerät schrieb der Künstler dem Singer-Songwriter im August 2015 einen langen Brief, der für immer unbeantwortet blieb. In dem Schreiben bat Rakowitz den Musiker um die Erlaubnis, ein Konzert im palästinensischen Ramallah mit Cover-Versionen von Cohens Songs zu spielen. Der Hintergrund: 2009 verhinderte ein palästinensischer Boykott-Aufruf ein Cohen-Konzert in Ramallah, weil der Musiker auch in Tel Aviv spielen wollte. „Leonard, I believe boycotts are problematic.“ schrieb Rakowitz, der sein seit 2009 laufendes Leonard-Cohen-Rechercheprojekt I’m good at love, I’m good at hate, it’s in between I freeze nun erstmals in Berlin präsentiert.

Ob Fensterrakel, Scheibenwischer oder Rasierklingen—dem Maler K.R.H. Sonderborg (1923–2008) war jedes Werkzeug recht, um seine wilden, zumeist schwarzen Striche, Linien, Wirbel und Farbbahnen auf die Leinwand oder das Papier zu bringen. Inspiriert von US-amerikanischen Abstrakten Expressionismus, ostasiatischer Kalligraphie und dem französischen Tachismus wurde er in den Fünfzigern zum Vertreter der informellen Malerei, zu deren Grundlagen das „Prinzip des Formlosen“ gezählt wurde. Besonders in der Nachkriegszeit galt diese Ästhetik als umstritten. Das Image des nomadischen Störenfrieds schien ihm zu gefallen: „Ich bin ein Maler ohne Atelier, immer in einem Provisorium. Und das liebe ich. Für mich ist die Malerei fast eine kriminelle Handlung. Ich bin wie jemand, der in den Keller hinabsteigt, um eine Ratte zu töten.“ Mit der Ausstellung feiert die Galerie Georg Nothelfer den hundertsten Geburtstag des Malers.