Sergey Kononov

2 MAY until 4 JUN 2025

Opening – 2 MAY 2025, 6-9 pm

At Bleibtreustraße 45, 10623 Berlin

Galerie Max Hetzler is pleased to present an exhibition of ten paintings by Sergey Kononov at Bleibtreustraße 45 in Berlin. This is the artist’s first solo exhibition with the gallery.

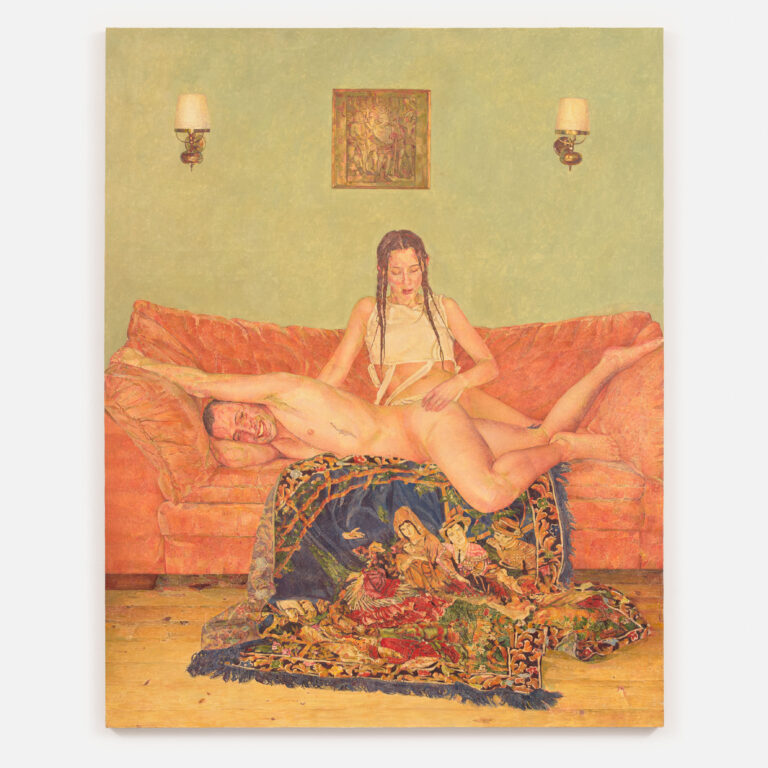

Sergey Kononov

Svetlana and Slavik, 2024

oil on canvas

199.5 x 159 cm.; 78 1/2 x 62 5/8 in.

(70851)

© Sergey Kononov, courtesy the artist and Galerie Max Hetzler Berlin | Paris | London | Marfa.

Photo: def image

In his intimate portraits, Ukrainian painter Sergey Kononov captures quiet moments of solitude or togetherness. Light-drenched and pooled in grainy, ochre tones, Kononov’s canvases exude a tenderness and familiarity reminiscent of a bygone era, thus probing the conventions of realist painting. ‘It’s important for me to capture a luminosity. I want to recreate the look of old films – that grain, that warm light – which I’ve loved my whole life,’ the artist explains.[1]

In the present exhibition, three closely cropped portraits depict faces obscured by cascading locks of golden hair. Subsumed in their inner selves, eyes closed or cast downward in martyr-like poses, Kononov’s subjects are imbued with the immediacy of photographic snapshots and the timelessness of ancient frescoes.

In other compositions, Kononov presents lingering glimpses of domestic solitude. A girl falls asleep in the study of an Italian palazzo, slumped over an open book. In another painting, she languidly rests her head on an ornate chair, seemingly caught in a moment of melancholy, the tiled floor beneath her providing a mosaic backdrop. Set in these anachronistic interiors, the contemporary body takes on a distinct ethereal quality, as though suspended in time and place.

Sergey Kononov

Nicole, 2024

oil on canvas

70.5 x 70.5 cm.; 27 3/4 x 27 3/4 in.

73 x 73 x 4 cm.; 28 3/4 x 28 3/4 x 1 5/8 in. (framed)

(70745)

© Sergey Kononov, courtesy the artist and Galerie Max Hetzler Berlin | Paris | London | Marfa.

Photo: def image

Kononov’s subjects are intimate by nature: they usually depict people he is close to, photographed and later eternalised in paint. In one work, a man rests in his companion’s lap, his arms slung around her upper body. In another, a couple sprawls across a sumptuous orange sofa, a vintage rug slipping out from under their bare bodies and onto the wooden floor. As enigmatic as they are exposed, these paintings radiate with raw vulnerability. Rendered against a flat swathe of vivid ochre, a solitary sitter confronts the viewer’s gaze in another composition. With fists raised, he displays his gold-ringed fingers.

Carnal, bold and nostalgic, Kononov’s paintings offer searing tributes to youth in a time of sociopolitical turbulence. In his depictions, Kononov is meticulous, as attuned to posture as he is to drapery and pattern. Each surface is rendered with care, built up from diminutive marks and haloed in a golden light that speaks to the artist’s varied influences – from Impressionism to Lucian Freud, Andrew Wyeth and Sandro Botticelli. At once haunting and familiar, fleeting and timeless, Kononov’s portraits unlock something of his protagonists’ inner lives, imbuing the quotidian with a new – and needed – sensuality.

Sergey Kononov (b. 1994, Odesa, Ukraine) lives and works in Paris, France. The artist’s work has been the subject of institutional solo exhibitions at Théâtre National de La Criée, Marseille (2020); Ukraine National Art Museum, Kiev (2015); and Museum of Modern Art, Odesa (2014). Kononov’s works are in the public collections of Fondation Francès, Clichy / Senlis; and Museum of Modern Art, Odesa.

[1] S. Kononov, ‘Sergey Kononov doesn’t like to be rushed’, Plaster Magazine, October 2024.

Thomas Struth

25 APR until 21 JUN 2025

Extended opening hours – 2 MAY 2025, 6-9 pm

At Potsdamer Straße 77-87, 10785 Berlin

Galerie Max Hetzler is pleased to present a solo exhibition of works by Thomas Struth at Potsdamer Strasse 77-87 in Berlin. This exhibition offers visitors a new and, at times, surprising insight into Struth’s oeuvre over the past four decades.

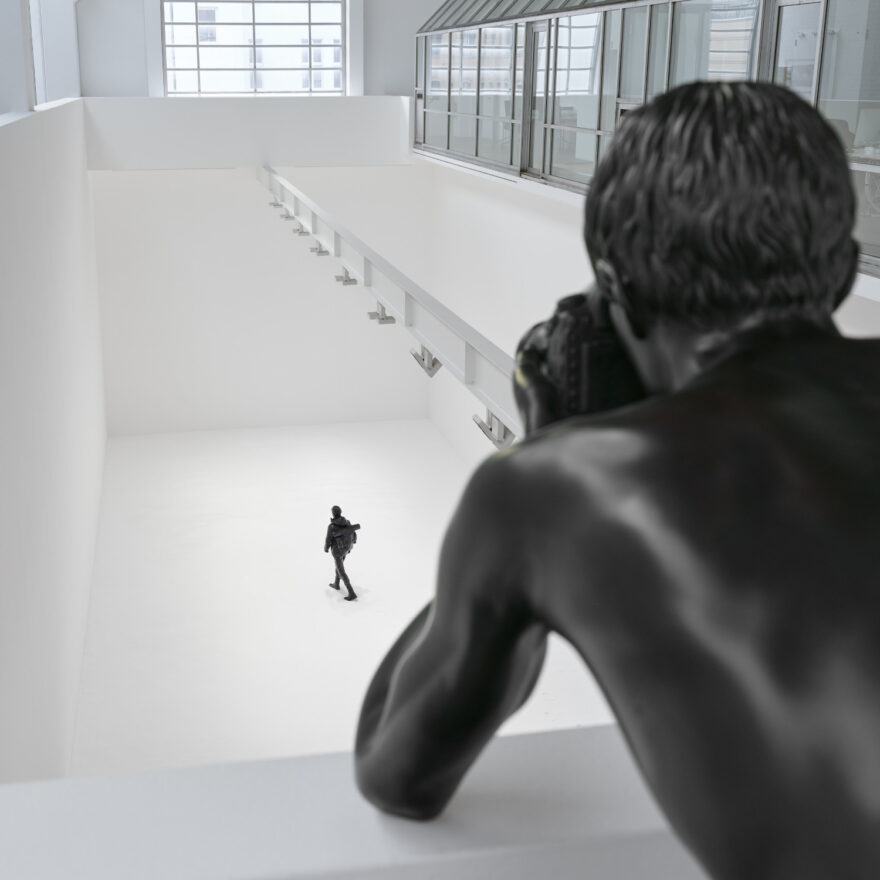

Thomas Struth

Semi Submersible Rig, DSME Shipyard, Geoje Island 2007, 2007

c-print

270 x 340 cm.; 106 1/4 x 133 7/8 in.

286 x 356 x 7 cm.; 112 5/8 x 140 1/8 x 2 3/4 in. (framed)

edition 6 of 6

(71036)

© Thomas Struth, courtesy the artist and Galerie Max Hetzler Berlin | Paris |

London | Marfa.

Thomas Struth’s work is characterised by his long-term and careful pursuit of themes that revolve, in various guises, around the relationship between people and their environment. His photographs, which harmonise forms of documentation and contemplation, capture today’s society through images of cultural spaces, as well as the natural world, portraiture and places of industrial and technological innovation.

At the start of the exhibition, one of Struth’s most recent works, Hinakapoʻula, Hawaiʻi 2024, draws viewers into the depths of densely wooded Hawaiian mountain. On the gallery’s far wall, Semi Submersible Rig, DSME Shipyard, Geoje Island 2007 depicts an industrial megastructure on the southern coast of South Korea. Its monumental size and four mighty pillars are emphasised by the perspective of the steel colossus which stretches up to the upper edge of the picture.

The earliest portraits in the exhibition, taken in the 1980s, constitute some of the artist’s most rarely seen works. Struth has long been interested in the depiction of people, as exemplified in his celebrated ‘Family Portraits’, which convey the intricacies of family dynamics. By contrast, the portraits in this exhibition focus on the relationship between subject and photographer. They seek to capture the presence of the individual and thus make visible an incomprehensible yet universally recognisable facet of humanity.

Since the late 1980s, Struth has also explored the special relationship people have with works of art, and the places that house them. His ‘Museum Photographs’ depict viewers confronting their own civilisation across the ages. In 2023, the artist spent several days at The Metropolitan Museum in New York, where he photographed visitors in front Édouard Manet’s The Execution of Maximilian, 1867– 1868 and Edgar Dégas’ The Bellelli Family, 1958–1967. In the resulting diptych, titled The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Diptych), New York 2023, Struth alludes to a historic connection between the two artists: following his death, Manet’s family cut up his painting to sell it in parts; the surviving fragments were later acquired by Degas, and were eventually reassembled in the late 1970s. Adding further layers to the work, Struth captures present-day museum visitors as they photograph the painting with their luminous smartphones. Spaces, times, cultures and attitudes are layered and combined, mediated via the artworks and their audience, and the viewer of the photograph.

The ‘New Pictures from Paradise’ represented in this exhibition date from the early 2000s, the decade that saw a heightened awareness of the fragility and importance of the natural world. In these photographs, Struth aims to depict a diversity so dense that individual components are no longer identifiable to the human eye and an impression of inaccessibility prevails instead.

A similar experience is at play in Struth’s ‘Nature & Politics’ photographs, initiated in 2007. In the present exhibition, these are represented through scenes from aerospace technology and nuclear fusion test centres. In Tokamak Asdex Upgrade Periphery, Max Planck Ipp, Garching 2009, a bewildering tangle of colour-coded wires conveys the unfathomable reality of advanced technology to the untrained eye. Its promise of future innovation remains abstract and intangible.

Thomas Struth (b. 1954) lives and works in Berlin. Struth has exhibited his work at Galerie Max Hetzler on a regular basis since 1987. Major retrospectives were held at the Guggenheim Museum,

Bilbao (2019) and the Haus der Kunst, Munich (2017). In 2016, his comprehensive solo exhibition Nature & Politics opened at the Museum Folkwang, Essen, before being presented at the MartinGropius-Bau, Berlin, the High Museum, Atlanta, the Moody Center for the Arts, Houston, and finally the Saint Louis Art Museum, Missouri. Other major solo exhibitions have taken place at international institutions including MAST Foundation, Bologna (2019); Aspen Art Museum (2018); The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2014 and 2003); Kunsthaus Zürich; Museu Serralves, Porto and K20, Düsseldorf (all 2011); Museo del Prado, Madrid (2007); Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago (2003); Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; and Dallas Museum of Art (2002).

Thomas Struth’s works are in the collections of the Art Institute of Chicago; Centre Pompidou, Paris; Dallas Museum of Art; Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin; Kunsthaus Zürich; Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebaek; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Museum of Contemporary Art, MOCA, Los Angeles; Museum Ludwig, Cologne; Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reine Sofía, Madrid; National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam; The Museum of Modern Art, New York and Tate, London, among others.

Leilah Babirye

Ekimyula Ekijjankunene (The Gorgeous Grotesque / Die prächtige Groteske)

2 MAY until 28 JUN 2025

Opening – 2 MAY 2025, 6-9 pm

At Goethestraße 2-3 & Bleibtreustraße 15-16

Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin is pleased to present Ekimyula Ekijjankunene (The Gorgeous Grotesque / Die prächtige Groteske), a solo exhibition of new works by Leilah Babirye at Goethestraße 2/3 and Bleibtreustraße 15/16. This is the artist’s inaugural exhibition with the gallery.

Leilah Babirye

Nakakeeto from the Kuchu Mutima (Heart) Clan, 2023–2024

charred beech, metal and found objects

265 x 104 x 90 cm.; 104 3/8 x 41 x 35 3/8 in. (67722)

© Leilah Babirye, courtesy the artist, Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and New York, Gordon Robichaux, New York, and Yorkshire Sculpture Park

Photo: Jonty Wilde

Language and history form the basis of Leilah Babirye’s work. Her sculptures and works on paper are characterised by the appropriation and reassignment of terms and categorisations. Her practice is influenced by her own biography, her experiences of homophobia around the world, and the antiLGBTQ+ legislation in Uganda that forced her to flee to the USA. In her multidisciplinary practice, she uses metal, ceramics, found objects, and hand-carved or chain-sawed wood, incorporating elements of traditional West and Central African iconography into a contemporary context. Her sculptures present real or imagined portraits of the Queer community from the African continent as well as her new homeland, representing an ever-growing LGBTQ+ elective family. While she previously worked on her wooden sculptures using burning as a tool of manipulation, she now uses a variety of other techniques including nailing, assembling, weaving and polishing to focus on the materiality of the works, before adorning them with found materials.

The current exhibition presents new sculptures made from wood, glazed ceramic and bronze, as well as a set of drawings on paper. The title both refers to the ostracisation experienced by members of the LGBTQ+ community and highlights the beauty of this community and Babirye’s work. The concept of the grotesque is of particular interest to the artist, not only for its art historical significance, but for the dualism it sets up between the repulsive and the beautiful. This juxtaposition is reflected in many details within the exhibition, from vibrant dripping glazes paired with used tyres, to smooth burnished wood paired with rusty found objects. Combined with larger-than-life organic forms which simultaneously intimidate and invite the viewer, all of these elements come together in what Babirye calls Ekimyula Ekijjankunene (The Gorgeous Grotesque / Die prächtige Groteske).

The sculptures range from a small group of figures to mask-like heads and faces, and monumental totems. The scale and presence of the works, which symbolically occupy the space around them, is an essential aspect of Babirye’s artistic practice. Some of the heads are encircled by voluptuous collars, while other figures sport body or hair ornaments made from discarded bicycle parts, such as chains or tyres – a symbol for the artist of progress and movement. As a motif, the mask simultaneously references West African handicrafts, the style of which Babirye appropriates, and how LGBTQ+ people in Uganda must conceal their identity. For Babirye, transforming discarded objects into something beautiful is an expression of the resilience of the Queer community. Its members are referred to in the Luganda language by the derogatory term ebisiyaga, which describes the husk of the sugarcane which is usually thrown away. By deliberately repurposing neglected materials, Babirye reveals the beauty in the supposedly worthless. The set of works on paper in vibrant colours, entitled Kuchu Ndagamuntu (Queer Identity Card), shows individuals from Queer and Trans communities or drag artists who Babirye has noticed in everyday life, on the street or while travelling. She paints them from memory. The portraits function as alternative passport photos, in which freedom of expression and true identity can exist unprovoked.

In the gallery space at Bleibtreustraße 15/16, the sculptures which form Abambowa (Royal Guard Who Protects the King), 2025, are lined up, side by side, on a plinth. Abambowa is the name for the highest guard in the traditional kingdom of Buganda. The titles of Babirye’s works often refer to names from the Ugandan clan system of pre-colonial history, which are based on plants or animals. In this way, the artist creates a sense of belonging which celebrates the members of the Queer community. The coded term kuchu (‘queer’), which can be found in some of the titles, is here afforded a dignified meaning.

Babirye’s oeuvre unites tradition, history and personal experience into a universal connection. Her work gives visibility and dignity to marginalised communities, celebrating resilience and diversity. Past and progress are not in opposition: ‘I always say that if you forget your history, you don’t know who you are and where you’re going,’ the artist states. ‘I can’t live in the present or look to the future without also looking back, and this back and forth is evident in my work.’[1] Grounded in her heritage, Babirye incorporates references into her practice and uses their artistic transformation as a means not just to survive, but to thrive and flourish.

Leilah Babirye (b. 1985, Kampala, Uganda) lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. The artist’s work has been the subject of institutional solo exhibitions at the de Young Museum, San Francisco (2024– 2025); and Yorkshire Sculpture Park, West Bretton (2024). Babirye’s work has also been presented in group exhibitions, including the 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia; Sainsbury’s Centre, Norwich (both 2024); Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; The Whitworth, The University of Manchester (both 2023); mumok, Vienna; The Africa Centre, London (both 2022); Coventry Biennial (2021); Hessel Museum of Art, Annandale-on-Hudson; Contemporary Arts Museum Houston; Bric, Brooklyn (all 2019); Trapholt Museum, Kolding (2016); and Kampala Art Biennale (2014).

Babirye’s work is held in the collections of the Columbus Museum of Art; Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; Herbert Art Gallery & Museum, Coventry; Hessel Museum of Art, Bard College, Annandaleon-Hudson; mumok, Vienna; RISD Museum, Providence; Sainsbury Centre, Norwich; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; and Xiao Museum of Contemporary Art, Shandong, among others.

[1] L. Babirye, in ‘Artist Leilah Babirye: “I want to help people feel a sense of belonging”’, Art Basel, 7 March 2024.