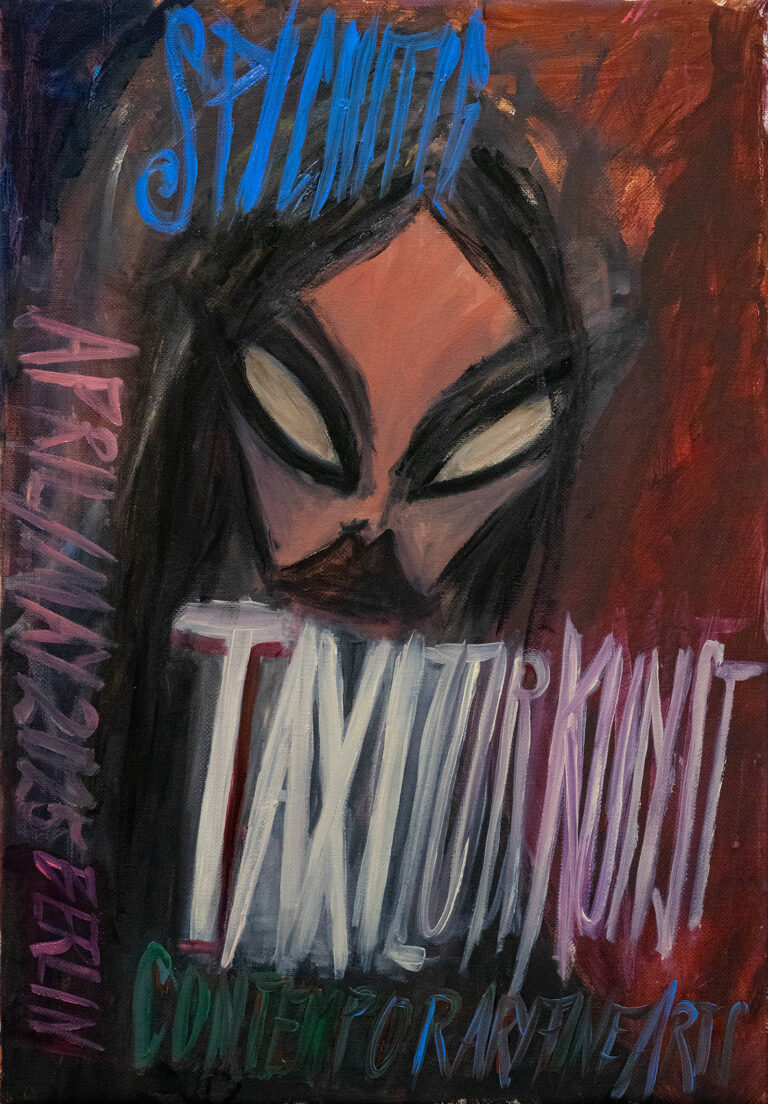

Tobias Spichtig

TAXI ZUR KUNST

12 APR until 31 MAY 2025

Opening – 11 APR 2025, 6-8 pm

Contemporary Fine Arts is pleased to announce the third solo exhibition of Swiss artist Tobias Spichtig titled Taxi zur Kunst for this year’s Gallery Weekend Berlin. The paintings, often referred to as reminiscent of French Post-war art or German Expressionism, feature the artist’s familiar vampiric or ghost-like figures and follow a loose narrative of cinematic scenarios of art in general. People attending concerts, openings or having dinner, a taxi driver, or a kissing scene, viewed by the painter as a passenger. Tobias Spichtig lives and works between Zürich and Berlin.

“Through Spichtig’s brush, bodies, faces, flowers, or mountains never quite emerge from their planar surfaces. His particular approach to painting eradicates depth and volume, delineating people and objects by means of hard lines, ensuring that each picture’s subject holds its pose in strange, morbid stillness…”

– Elena Filipovic in ihrem Ausstellungstext, veröffentlicht anlässlich der Einzelausstellung des Künstlers „Everything No One Ever Wanted“, Kunsthalle Basel, 2024.

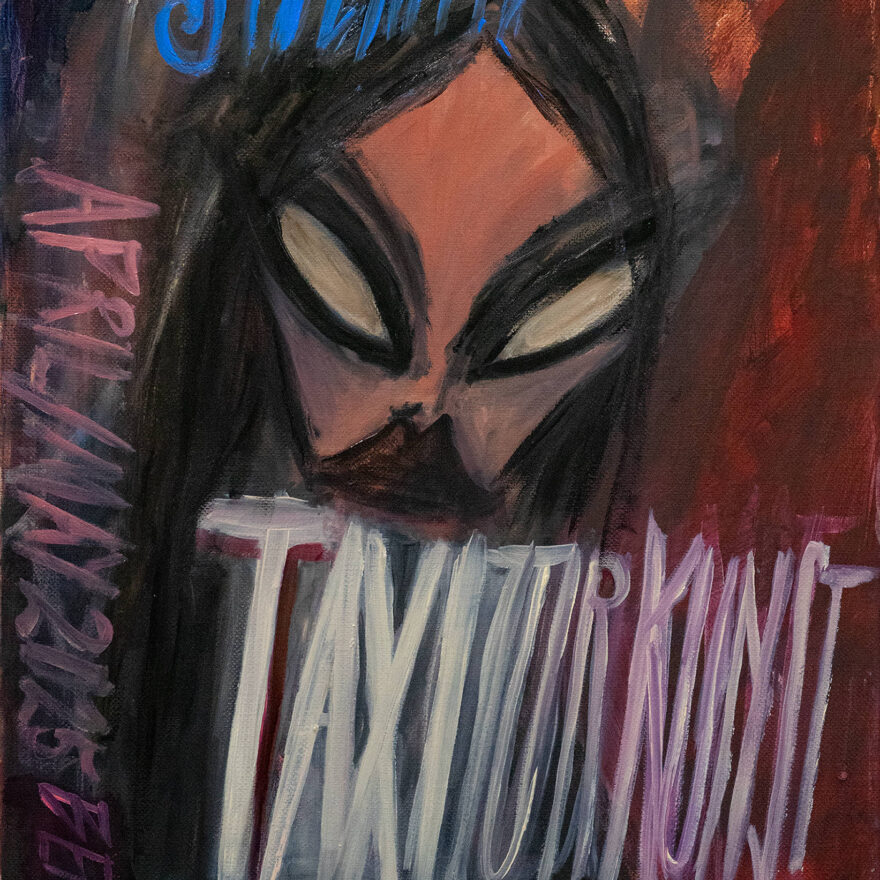

Tobias Spichtig, Einladungskarte „Taxi zur Kunst“ 2025.

Courtesy: Contemporary Fine Arts.

„His painting resonates just here, between embarrassment and seriousness, humor and melancholy, honesty and deception, closeness and distance. He’s chasing beauty through it all, and he’s having a good time.”

– Benjamin Barlow “Keeping It Together”, Blau International, No.12, 2025.