HUDINILSON JR.

2 MAY until 26 JUL 2025

Opening – 2 MAY 2025, 12-9 pm

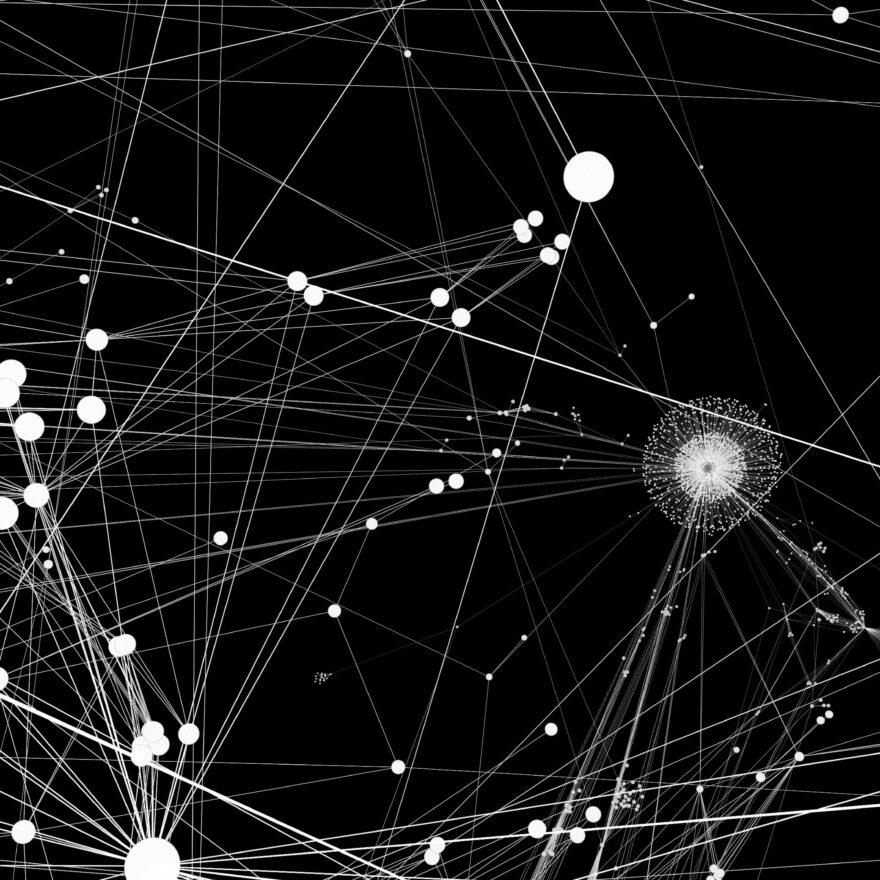

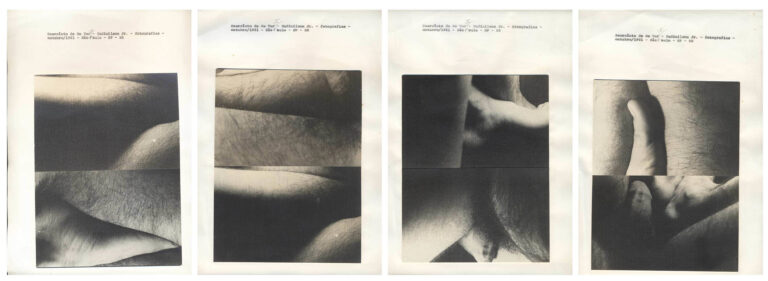

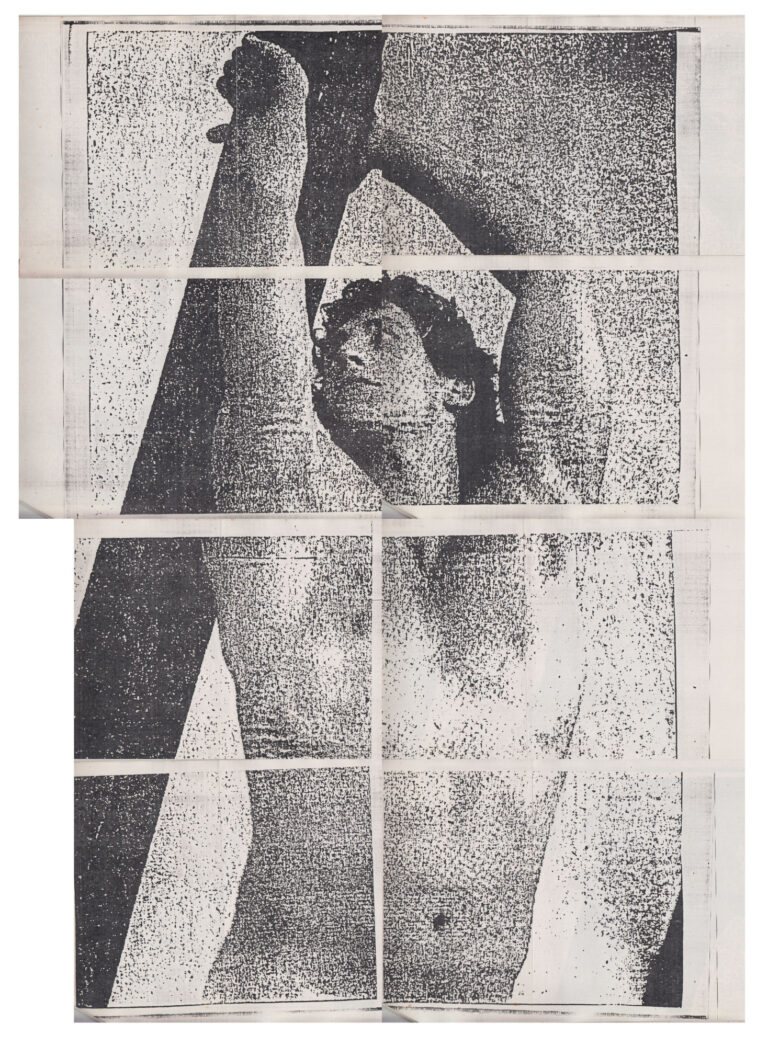

Hudinilson Jr.,

Exercício de me ver II, 1981,

courtesy of the Estate of Hudinilson Jr. and KOW, Berlin.

Hudinilson Jr. (São Paulo, Brazil) was one of the most influential yet underground figures in Latin American art since the late 1970s and 1980s. Through his captivating oeuvre of performances, artist books, extensive Xerox assemblages, and sculptures, the artist operated at the intersection of the intimate and the public sphere. Hudinilson Jr.’s artworks explore representations of bodies, including his own, making visible both self-perception and external observation. His work presents experimental forms of ‘seeing’ oneself and others. Desire, intimacy, and sexually charged modes of observation become tangible.

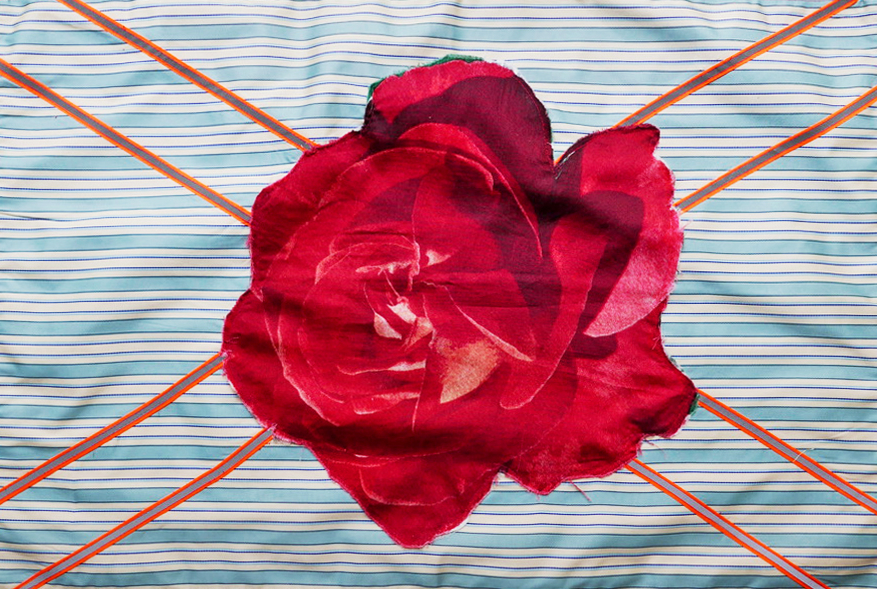

Hudinilson Jr.,

Untitled, 1980s,

courtesy of the Estate of Hudinilson Jr. and KOW, Berlin.

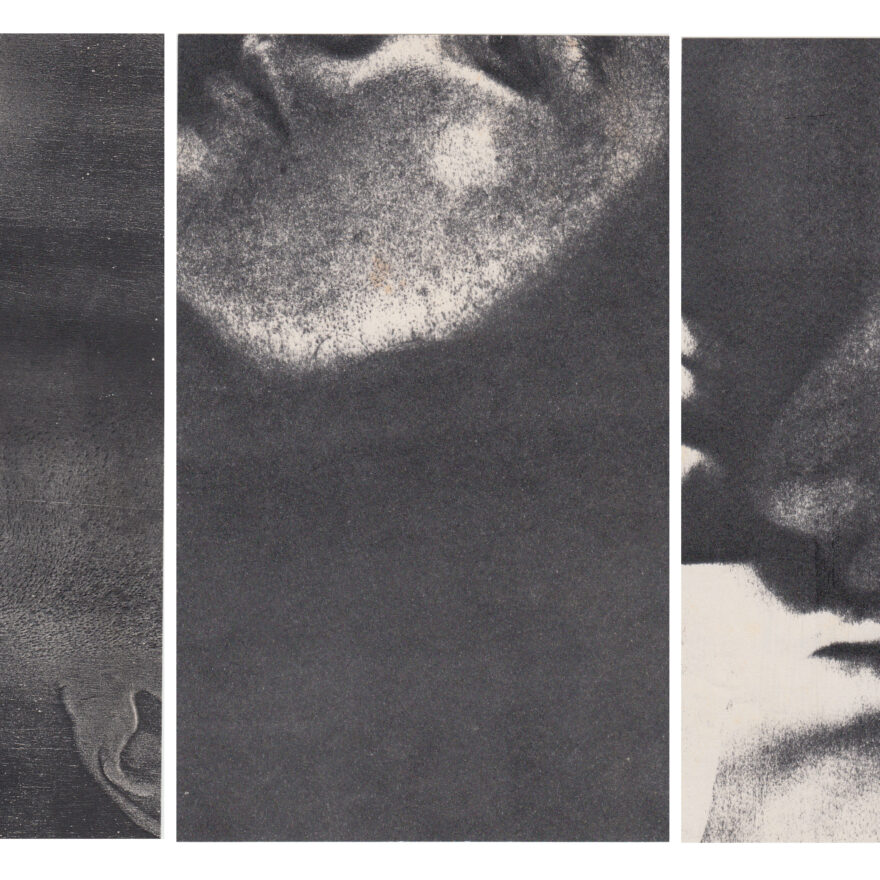

Hudinilson Jr.,

“Narcisse” Exercício de Me Ver II, 1982, documentation of the performance, detail,

courtesy of the Estate of Hudinilson Jr. and KOW, Berlin.

Today, Hudinilson Jr. is being re-evaluated as a pioneer of conceptual and activist art that captures and documents queer gazes and bodies, situating them not only in the personal but also in the public space. KOW considers itself fortunate to represent the estate of the artist from São Paulo, who was born in 1957 and passed away in 2013.