FLASHBACK

In conversation with Rudolf Springer

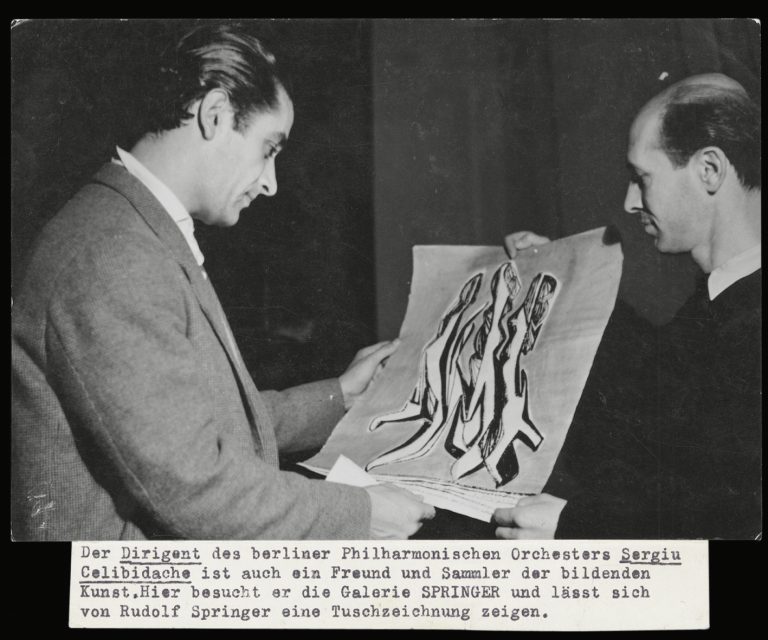

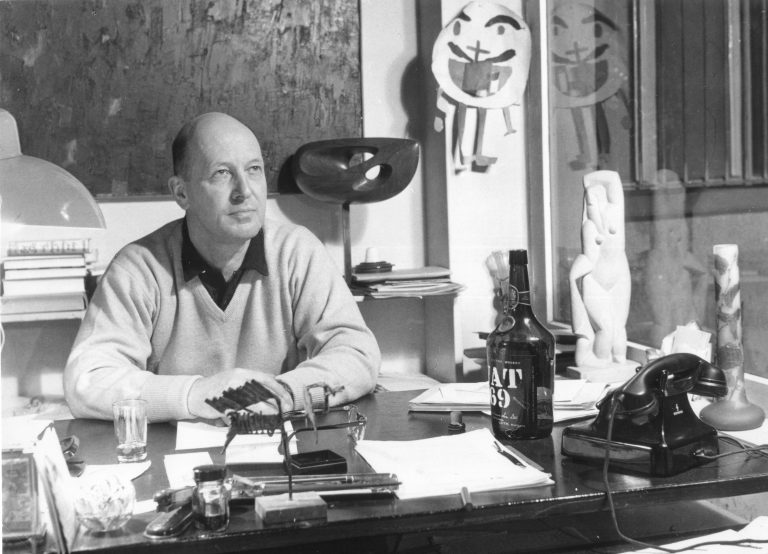

Claus-Dieter Fröhlich, one of the most loyal friends and clients of the Galerie Springer, has dedicated himself for several years with downright scholarly commitment to the analysis and evaluation of the visitors’ books of the Galerie Springer from 1948 to 1963. In this context, he conducted the following interview with Rudolf Springer (1909 – 2009), the legendary founder of the gallery—here reproduced in an abridged form—in 2002. We thank the author and Contemporary Fine Arts for their kind co-operation and uncomplicated permission to publish this interview online.

Naval officer Rudolf Springer, 1941. Courtesy Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin

Claus-Dieter Fröhlich: Herr Springer, you told me recently that the famous publisher family you stem from was originally Jewish. I presume that, like so many Jewish families, it converted to Christianity in Germany under the Kaiser.

Rudolf Springer: The founder of the academic Julius Springer Verlag was my great-grandfather, Julius Springer. He converted from the Jewish faith to Protestantism. Very many acquaintances in his generation did the same thing; many of my relatives from the Julius Springer line descended originally from Jewish families.

Well, the Nazis didn’t bother much about that; according to their racist ideology, you were still a Jew or at least a…

One of the sons of old Julius is my grandfather, Fritz Springer. He and his older brother, Ferdinand Springer, were both already born as Protestant children. The Jewish question with the Nazis played out on the basis of grandparentage, and both grandparents of Else Haver, my mother, were Protestant and both of my father’s, the son of Fritz Springer. But because our family was well known, they did something very mean to us; they applied the Nuremberg Laws twice, so to speak, and went back four generations. And there many were Jewish, which of course had negative consequences for us. My brother, Robert, who then died in Russia as a medical corps sergeant, had to specify for his medical studies that he was regarded under the Nuremberg Laws as quarter Jewish. When I was conscripted I said that I did not know anything about any sort of Jewish descent. Toward the end of the war I, or rather my unit, received a letter which asked whether I was still in this unit and whether it was known that I was Jewish, or a Jewish half-breed. I said then that I had a brother, Robert, that, however, he had become my brother through marriage. That is, I lied. And so, the matter was settled.

You personally, then, did not suffer any discrimination?

No. But I was always in immediate danger because I behaved the way I do (you know a little about how I am); I was not very well liked by the Nazis already on general grounds. I remember, for instance, I was an Allianz representative before the war and did not stop this work even after I was conscripted. My former secretary, Frau Tuch, was a full Jew and emigrated to South America. We had arranged that she would send a certain telegram once everything had worked out well with the emigration. We had agreed that she should write, “Fiffi has arrived here with us on this journey in the best of health”. Fiffi was the code for saying that things had worked out for her. Then one day I was picked up by two men from the Gestapo and immediately interrogated behind closed doors. One of them said, “You received a funny telegram saying so on so”. I said, “That’s not funny. Fiffi is her dog whom she loves a lot, and she was supposed to tell me immediately if the journey to Brazil had gone well for him”. Then he asked lots of other questions and the Fiffi question once again. I said, “I answered this question for you quite precisely ten minutes ago. Unfortunately, I cannot tell you anything else. I also do not know whether the dog is still alive, but at least he arrived in a good state, and perhaps your colleague here can write these things down so that you do not have to repeat such a simple question”. And after I had said that, they let me go.

You told me that, in contrast to your comrades who either had the Bible or Werther’s Sufferings with them to read, you had a book with the significant title, Art or Kitsch. What was in this book and what was so decisive about it for your future path in life?

That was a kind of Bible for me; I knew it inside out. I have tried many times to get hold of it again because I lost it somehow at the end of the war. Now I have a wonderful copy of it with a dedication from you and I am very glad about that.

You say that the contents of the book were not the decisive point since you had learnt them almost by rote. There must be something about this book that moved you to take a certain direction.

My interest in contemporary art and my interest in judging whether something is kitsch or not.

This book was therefore a guide that was important for subsequent decades. Can it be put that way?

Yes indeed. After all, I became an art dealer. After the war I was at first in Malente for two years, from 1945 to 1947, because my later wife, Suzanne Mahenc, whom I could not yet marry, but with whom I already had a relationship as a soldier, had to leave Paris. She did not want her hair to be shorn off because she had had a relationship with a German. I had, after all, officially acknowledged our daughter, Catherine, as my child at the town hall registry. And pregnant with our second daughter, Suzanne came to Berlin to my parents’ place. My father then ordered that she should go to Potsdam because Berlin was being bombarded so heavily. There she would be in less danger. There, my second daughter, Véronique, was born in 1944 in September or November, I can’t remember off-hand. I then guided Suzanne with the two children to Holstein because I was convinced that the war would be at an end before Holstein was occupied. And in this I proved to be correct.

But then you returned to Berlin very quickly. And in Berlin, as we know, you made contact with Gerd Rosen. How did this contact come about?

It came about through a man whom I knew whose surname was Werner, a painter…

Theodor Werner.

That’s right. I asked him what I had to do to become an art dealer and he said that the best thing to do was to go to Rosen because he dealt in modern art, and also had antiques and old paintings. He was, so to speak, a dealer in everything. Rosen had originally been a dealer in old books near Wertheim. He was also half Jewish, and Werner told me that I could learn a lot from him. I then went to him and said that I would like to work for him. He represented Trökes and Uhlmann and many others whom I then later represented because they all left Rosen. When the old Reichsmark was replaced by the new Mark, namely, he paid everything he owed these artists just two days before the currency reform.

Rudolf Springer at his dog Rico, 1954. Photo: Nina von Jaanson, Courtesy Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin

Rudolf Springer and actress at dance, 1955, Courtesy Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin

Some artists you have already named, Trökes and Uhlmann, but also Wolfgang Frankenstein and you yourself were for a time in this post-war period the manager of the Galerie Rosen.

I was the first manager of the Galerie Rosen who was not an artist. I remember that Rosen, when I told him during my visit, what I would like to do, said at the end of the conversation, yes, do that by all means, I would like to take you on, but do you love art? I said, that’s why I have come to you, because I love it. I want to get to know the people through you and make further contacts with modern artists through my activities.

You then opened your own gallery in 1948 in your parents’ house in Zehlendorf, where you still live today and deal in art. That was where it all started. What were your motives for becoming self-employed, loosening your ties with Rosen and opening your own gallery?

Various motives. The main reason was that Rosen’s artists left him when the currency reform took place. That was the reason why I so quickly had an opportunity to become independent.

Yes, but it was surely not so easy to start dealing in art in 1948, at a time when most people were preoccupied with getting their hands on potatoes or firewood. What was the art-dealing scene like at this time?

There were only four galleries in Berlin. One of them was Frau Bremer, then there was Walter Schüler, and then another one who, I believe was in the…

… Bundesallee; there was the Galerie Franz.

That’s right. Franz had been a prize boxer.

That is not a bad preparation for being an art dealer.

Yes. (Laughs) And I became very well-known because I was one of the first who started from scratch.

The first artist to whom you gave space on the walls of your parents’ house was Hans Uhlmann.

That’s right.

You have one of his drawings in your room from the first year,1948. Did you have an especially trusting relation with Uhlmann because of his biography, or was it solely his artistic potential which had persuaded you?

Both.

What did your parents say about the activities in their house?

They found it very exciting and also supported it. At that time, I had separated from Suzanne after we had, so to speak, created two more daughters in Holstein. I separated from her because she did not get along at all with my mother. They were both very dominant persons. For my mother there was no ‘perhaps’, but only yes or no, and that was the case for Suzanne as well. Both of them were not exactly diplomatic or prepared to make compromises. Suzanne was also very independent and has remained so all her life. She is still alive and as a woman of over 70 now has bright green hair and a short urchin cut.

Courtesy Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin

Courtesy Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin

With your second exhibition showing works by Mac Zimmermann you started a visitors’ book which you continued without a break until the end of 1963. I would like to recall all those who appeared at the second exhibition in Zehlendorf. They included the painters, Wolf Hofmann, Heinz Trökes, Werner Heldt, Willi Strecker, Unica Zürn, Hans Thiemann, Curt Lahs, Theodor Werner, Bernhard Heiliger and even Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. With a few exceptions they were all artists from the Galerie Rosen. Did these artists now have hopes of having exhibitions at your place in Zehlendorf, or did they have a general interest in art, or, as a third option, since times were tough, did they simply enjoy the cake and wine you offered them?

All three together. They were glad that there was someone who did not cheat them, to put it plainly. And they simply found it good that new blood was coming in and therefore liked taking part. Shortly thereafter, in 1950, I got to know the top Frenchman in the occupation army; I no longer know precisely what his name was. He made a room available to me in the first new building on Kurfürstendamm, in the Maison de France, at a very low rental, because he was of course interested in having the French appear with a man who was interested in modern art.

After you had exhibited only German artists, with one exception, up until April 1950, that changed completely when you changed premises in June 1950. The very first exhibition in Maison de France was dedicated to Joan Miró. The move thus brought a completely different international profile. All at once, the international artists were there whom you have accompanied throughout your entire further life as a gallery-owner to the present day. What triggered that?

Trips I made to Paris. At that time, I had excellent connections with all sorts of well-known people in Paris. For instance, I had got to know Cocteau. Then I became acquainted with André Breton, and so forth. I corresponded with them and visited them. That’s the way it went and I made progress.

So, you picked the artists directly in Paris. Can it be described that way?

That’s right.

When one looks at the list of artists in the following years, it is striking that there were very strong ups and downs. Local ephemeral artists such as the hobby painter, Karl Maeder alternated with internationally renowned artists such as Alexander Calder, Willi Baumeister and Wols. Were you aware of it at the time, or did they all have the same status for you?

They all had the special status of being good artists. I never thought much of the so-called specialized gallery. To show art of just one sort is not my cup of tea at all. That’s just like when you like eating something very much, and eat it all the time, then it loses its taste for you. That is, I took on various artists, and also various directions because I am that way. That corresponded to my nature.

You had an appetite for home-grown carrots and exotic fruits to an equal extent?

That’s it precisely.

Courtesy Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin

CDF

Your happiness in one room in Maison de France did not last long. You said the French… I ask myself whether it was the commandant of the city or the top military officer or the top cultural officer.

RS

That was all the same at that time.

CDF

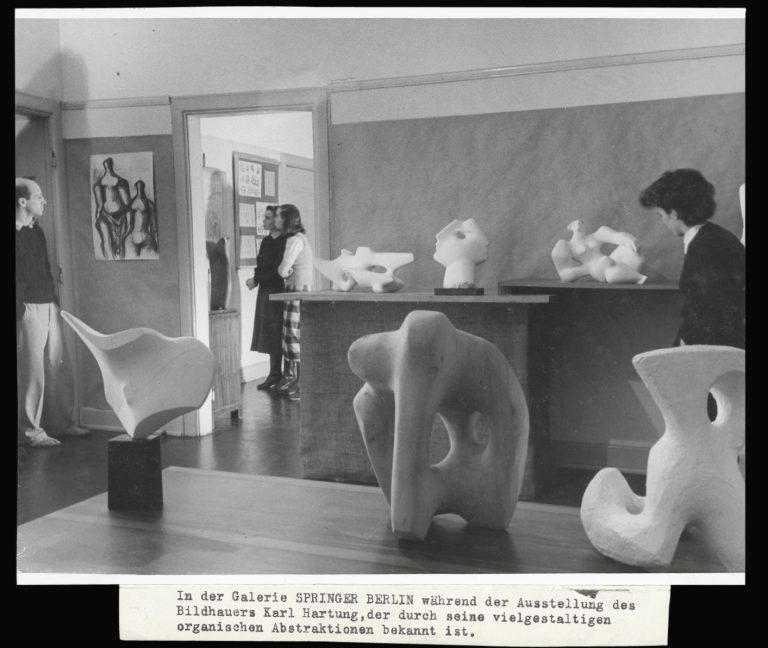

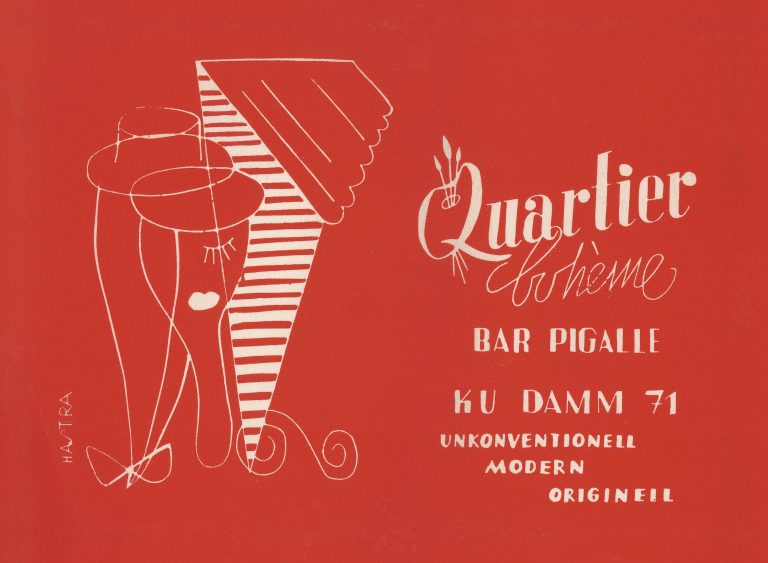

He threw you out. How did you then get on? You told me, at first you found a single wall in the so-called Quartier Bohème, where Rudolf van der Laack was still a bartender before he had a similar position with Anja Bremer. The Quartier Bohème was situated on today’s Adenauer Square where a well-known Berlin Playboy had one of his establishments. In April 1953 you had your first exhibition there. Can you say something about this period and the Quartier Bohème?

RS

The Quartier Bohème was the first pub in all of Berlin where you could order a quarter liter of red wine in a small carafe along with French fries. And it was also very well patronized. The first exhibition in 1953 was with Karl Heinz Kliemann, and after that I showed Guido Jendritzko. Jendritzko was also at the art school; he was a student of Hartung’s. Hartung once said to me that I should not let him in at all because what he saw in my exhibitions I would see in the same form three days later in his work.

CDF

At that time when you had the wall in Quartier Bohème, you also presented a young ‘wild’ artist before this label had been invented. I am referring to the multi-talented artist, Klaus Kinski.

RS

That’s right.

CDF

… who, as we now know, was not only a genius actor. He also had a very early expressive phase as a poet and also in the fine arts. Please tell us something about that.

RS

One day the manager came to me and said, “I have a young artist whom you should show some time. His name is Klaus Kinski”. I said that he only had to show me his stuff and I would decide whether I wanted to exhibit it. And then he came to me with some drawings, very energetic, I believe, in charcoal; there were in any case broad lines, not pencil drawings, black-and-white and figurative. And I said, “I would very much like to show them”. One day before the opening, after the invitations had long been sent out, Kinski came to the exhibition that was being set up. He came already in the morning around ten o’clock and sat down, or rather flung himself down at a table. The pub was still empty. Kinski had an enormous packet of sandwiches in a kind of paper that you could get at that time, which could be folded over and over again and was grease-proof, and the paper was very creased. He had about eight sandwiches in this paper and started eating them. Then he threw my dog, a bull terrier I loved very much, a sandwich.

I said to him, “Herr Kinski, please don’t feed the dog, it’s my dog and I am the only one who should feed him”. He couldn’t have cared less and threw him another sandwich. And then I said, “Herr Kinski, I just asked you not to feed the dog because I am the only one who should feed him; you can pack up your pictures. The exhibition is off”. And then he shot up and said, “What’s that supposed to mean, it’s off? That has been agreed”. I said, “I tried to reach an agreement with you about feeding my dog, and you also did not stick to that. So, I will not stick to the agreement about the exhibition. You can pack up your pictures and go”. Then Herr Hagedorf, the manager, came to me, because Kinski had immediately raced off to him, and tried to calm things down. “Please don’t be so rigid.” I said, “I am not rigid, I am only being consistent and I will not go ahead with the exhibition”. Some friends said to me that I would surely be beaten up the next day because Kinski knew some people he could get to do the job. So, I went to the opening that did not take place. There were a few critics there who went to every exhibition anyway because there were so few. I told them the whole story. Kinski then had more press than many other young artists I had exhibited.

CDF

So that was your only art exhibition without art works, but with the press.

RS

That’s right.

CDF

In following years, you also discovered the first artists who became famous very quickly, such as Friedrich Schröder Sonnenstern. Would you like to say something about this really very peculiar and gifted artist?

RS

Friedrich Schröder Sonnenstern came from a very poor family from Königsberg and was, I believe, the youngest son of thirteen siblings. In any case, his works made him very famous. They were very small formats, mostly colored pencil on paper, and the corners were cut round. There was also a piece of text below the images. They were very hard to sell for 60 Marks, but some people did buy a few, for instance, I sold a lot to the actor, Ernst Schröder.

CDF

It is said in general that an artist has only become really famous when he is faked, and that happened later on to Friedrich Schröder Sonnenstern. For a time in Berlin there were more fake Schröder Sonnensterns than genuine ones.

RS

… and I was responsible for judging that. I could always do so and was regarded as a real expert. They always came to me. Sonnenstern then signed a lot of fakes because he could make money from it. The format was also enlarged to a certain size of cardboard. I had wonderful experiences with Sonnenstern. But then I recommended him for a surrealist exhibition in a Paris gallery and sent along some works. I already fixed a selling price of 200 Marks because we were now already two galleries. It sold quite well. At the end of this exhibition, Friedrich Schröder came to me and said, “In the last two years you have been able to sell almost nothing for 60 Marks, and now suddenly there are dealers in Paris who pay that several times over. So, I am leaving you”. “I can’t do anything about that,” I said, “You only cost me money anyhow. Lead your life how you want”. He then continued to visit me regularly and always said, “With you it was best. And the money afterwards plays no role at all”. Every time he came to me I let him conduct the famous opera which was the following, “My darling has shat”. That was the entire libretto, the only line in the opera, repeated over and over again and underscored by strings and brass. He always stood there and first described the orchestra: 200 first violins, 100 second violins, violas, brass; he laid down everything precisely and then he started. He made movements like a conductor and sang the unchanging song, “My darling has shat”. Then he had the fictitious orchestra swell up very quickly. Always the same line. But the funny thing was that he did not say, “My darling has shaaaaat,” but, “my darling has shaaaaaa…,” and then he let his voice crack. (sings) I almost died laughing.

CDF

A work which unfortunately has never been performed on the opera stages of this world.

RS

(laughs)

Photo: Hildegard Zenker

Courtesy Community of heirs Hildegard Zenker / Estate Hildegard Zenker Berlinische Galerie

CDF

One international artist for whom you organized his first exhibition in Germany was Piero Dorazio, a connection which very quickly became a friendship.

RS

There was an exhibition, New European Painting, at the art academy on Stein Square. Naturally I saw it with great curiosity and there I found the best artist, Piero Dorazio, and I made enquiries about him. He was in Berlin for this exhibition and had himself been involved in hanging it. He was not as young as the other artists participating, at the end of his twenties. In a certain way, Dorazio had already positioned himself in Italy, and I found him to be the most interesting man. Of the three paintings exhibited, I bought the smallest one which was supposed to cost 450 Marks. I said to the management that I was interested in meeting him, and so he came to me. He then broke a glass table at my place and for the repairs I then deducted 200 Marks from the purchase price for the painting, thus paying 250 marks. I kept the painting, and still have it. I then traded very, very many of Dorazio’s paintings. They then changed. Afterwards he made also very large paintings with simple means. Of these I bought very many cheaply and sometimes only after several years, but in part sold them at a very high price. Some went for more than 100,000 Marks.

CDF

Fewer and fewer local artists had a command of the program of the second half of the 1950s, about the time when you did the first Dorazio exhibition. For this exhibition, international artists went in and out of the Galerie Springer in a continuous stream which, in the meantime, had moved to Kurfürstendamm 16 on the corner of Joachimsthaler. I name, for example, Reg Butler, Emilio Vedova, Henri Laurens, Kenneth Armitage, Max Ernst, Hans Bellmer and Unica Zürn, William Dole and Sam Francis. And that was at a time when Berlin was in the middle of the Cold War. I recall just a few facts from contemporary history: 17 June 1953, the Hungarian uprising in 1956, the Khrushchev ultimatum in 1958, against which the Western allies stood firm, but many residents of Berlin did not. As I still clearly remember, before the start of construction on the Wall in August 1961, there had already been a first exodus in the city after the war. Were you not affected by this at all? It was surely not very easy to draw internationally renowned artists to the city at this time?

RS

That had to do with how I dealt with them. I said that Berlin was now at a very interesting point in its development. A lot was being rebuilt and things would become as they should be. Berlin is in any case a wonderful city. You must have a look at it, then you will understand what I mean, and so on. Laurens, the famous sculptor, by the way, I exhibited once more in the Maison de France. I did not do that in my gallery on Kurfürstendamm, but in a room of Maison de France from which my gallery in the meantime had moved. At one of the openings there, by the way, Hans Bellmer met Unica Zürn. On the whole it was a heavenly time for me.

CDF

I come now to the next artist. They can’t all be counted, they are so numerous, so that we will have to restrict ourselves to a few, an outsider. Goethe once said that everything he had brought together in the area of poetry was nothing compared with his success in the area of the theory of color. In December 1961 you exhibited watercolors and copperplate engravings by Henry Miller. Many people did not know until then that the famous creator of the Tropic books also worked in the fine arts. You then also had a close relationship with him.

RS

I had heard of Henry Miller and had also purchased one of his books, and then I really wanted to meet him. The day I wanted to write to him, he came into my gallery.

CDF

I know that Henry Miller came to Berlin also under the auspices of a DAAD program. Could you say something about your personal relationship with Henry Miller?

RS

I had a famous portrait of him made by Marino Marini. Then we went to Italy together and lived there for a while. Henry Miller said tome beforehand, “We will surely often have invitations here. You must decide where we have to go, and where not”. Of course, there was immediately an invitation from the son of the Fischer Verlag and his wife, Gottfried and Brigitte Bermann Fischer, who had a house there. We accepted. At first, we played ping-pong.

Miller played with the hostess. She was wearing a very elegant dress and afterwards, I will never forget, her dress was wet from perspiration. She won and Miller said, “I let her win. After all, afterwards we will be served dinner”. And at dinner he was also completely unabashed. We were served corn cobs which are normally eaten by hand. He refused to do so. So, they went back to the kitchen and the corn was scraped off for him there. And then he ate the corn from the plate.

CDF

Miller was not a Fischer author. His novels and stories had been published by Rowohlt since 1953. He was a well-established author, at that time already in Germany. How did the public in Berlin react to his art?

RS

I can’t say anything about that. I can only say that my wife, who is also a painter, only got to know Henry Miller through his art. She also has the only Henry Miller watercolor that is still in our family. She says that, despite all the naiveté of his way of painting, he has genuine talent.

CDF

I would like to go a little bit further. Despite the Wall and the barbed wire, you have always made an effort for artists from East Germany who, in contrast to the official state artists, had a very hard time there. There was spying and persecution in a very bad and, unfortunately, very German way. I am referring to Altenbourg, whose real name was Gerhard Ströch. In February 1961 you dedicated an exhibition to him, six months before the construction of the Wall. Altenbourg, however, was also a very early guest at the Galerie Springer. Already ten years before that he often visited the gallery. To the present day, this great talent has not been sufficiently appreciated. You recognized his artistic potential very early on and furthered it.

RS

Yes, my attention was drawn to him by a university teacher in East Germany. I wrote to him immediately, and then he came to Berlin. Later on, I also traveled to him. He was very peculiar, Altenbourg, and very cultivated. I remember once when he was staying with us, I was away one afternoon, and he sat in a heated room reading a book. When I returned two or three hours later, he was still sitting there in exactly the same way, only that he had read a few hundred pages more. That was typical for him. I liked him very much, and he liked me very much too. I always tried to get him over to the West, but he was unable to make the break because he was so used to his house. It was his parents’ house. He also had a sister for whom he always went shopping in Berlin, for elegant underwear and suchlike. Altenbourg himself also dressed very elegantly. He had his suits tailored from fabrics which he got hold of somewhere. Frau Ströch, his sister, is still alive today. She inherited all that. He died in a car accident. And somewhat like the Berliner I have always been, I said, when the accident happened, “That doesn’t matter, he wouldn’t have done anything more amazing anyway”. And that is also the way it was. He became very well known, but his early works are by far the best. Right now, I am after a drawing which I had sold very early on to the head of the West German mission in East Berlin. It was called, The One-Eyed Man, and was very large and must be worth a lot today. I am trying to find out who has it now because it belonged to the official representation of West Germany in the zone.

CDF

Oh yes, the diplomatic mission of the Federal Republic of Germany.

RS

Yes.

CDF

Here we discover, completely by the by, that, if I may say so, at the age of almost 93, you are still an active art dealer.

RS

Yes, I am, when I can do it. I am still interested in it.

From left to right: Johannes Gachnang, Markus Lüpertz, unkown lady, Rudolf Springer, Christa Dichgans, Norman Rosenthal, Kay Heymer.

Courtesy Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin

CDF

I am speaking with you about your gallery, the Galerie Springer, which is almost as old as the Federal Republic of Germany. It was always located in the new West Berlin. Was that so because the galleries of Rosen, Bremer, Schüler and Nierendorff were also situated close to Kurfürstendamm?

RS

Yes, where else should it have been situated? In East Berlin?

CDF

In the period before the Wall, that would have been conceivable.

RS

No, not for me, even though some things were done very well in the East.

CDF

As far as Altenbourg is concerned, you were spot on at the right time. I would like to come back once again to the East-West problematic. Your public in pre-Wall times during the early years of the gallery was mainly a Western public. If I put to one side artists and gallery-owners, in your visitors’ book there are surprisingly many actors among your customers. There are regular entries by Sigmar Schneider, Franz Nicklisch, Bernhard Minetti, Alfred Balthoff, Friedrich Maurer and, of course, by your dear friend, Berta Drews. What made the Galerie Springer so attractive for actors and, as it seems to me, precisely for the stars from the former Schiller and Schlosspark Theater?

RS

Why did they like coming to me? Simply because there was a pleasant group of people there. They were respectable people who often did not know each other. You could always be sure that you would find interesting people in my gallery.

CDF

And this special relationship with the actors of the Schiller Theater, was that also a reciprocal relationship, that you were also very much interested in theater?

RS

No, not very much.

CDF

Not very much. And can you say something more, an anecdote or something? You used to tell stories about your special relationship with Berta Drews.

RS

Berta Drews was close friends with Ernst Schröder. They had a relationship with one another. The old George was dead. And once I travelled with Berta Drews, who was such a folksy type, to Sylt. I had friends in Keitum who had a house there, and we met them there. I can remember exactly: I drove off at 7 o’clock in a small old Ford, one that was round at the back, with Berta Drews because the car could not go faster than 80 kilometers per hour.

It was summer, and as we were driving past a meadow, she said, “Please stop here. I would like to go down here”. Then she went barefoot, completely sure-footed, through a meadow. I cannot walk barefoot. That is much too prickly for me. But she walked off, picked up her skirt and walked firmly into a wet area where this and that was growing, and where you could not know where you were treading. I never forgot that, this movement. I have only experienced that one other time, also with an actress, the Norwegian wife of Rolf Nesch. She had the same way of behaving. There are actors who do that completely artificially, what they act, and then there are others that do it completely as themselves when they act. I have always seen the difference very clearly.

CDF

Herr Springer, to conclude I would like to ask you a famous question. If you could start all over again today, what would you do differently, and what would you do exactly the same way?

RS

I can only answer the question the following way. It is pointless because, if you say to something or other, ‘If I had not done that, then…’, because I don’t know at all what would have happened if I hadn’t done that. Or if I had always found someone very good, and he had behaved toward me in a lousy way, then he had probably treated me in a lousy way because he had reasons for doing so. But they do not have to be reasons which I had given him, but reasons which we had created for himself. In any case, I always liked my vocation very much. I did not make a lot of money, but, thank goodness, had my father’s family in the background. The money I earned went straight back into the gallery.

CDF

Is there something that you would call an errant path, an artistic wrong track? Have you thought sometimes that you would under no circumstances exhibit this or that artist again?

RS

I don’t know. I had a real relationship with all of them. Perhaps I would no longer have such a relationship on the basis of my experience today. But under the circumstances at that time I was very committed and I believed in them.

CDF

You liked to decorate the letterheads of the Galerie Springer with quotations from famous contemporaries, such as Picasso’s statement that in these miserable times it was above all a matter of arousing enthusiasm. That is a maxim which is today again very relevant. But humor was also never absent. Like Tucholsky, you were never able to understand how two people could be of the same opinion. You yourself were always of two opinions. Heraclitus’ “panta rhei” always had great meaning for you. It is a saying which overcomes transience, which you have overcome already with your fifty years of work as a gallery-owner in Berlin. Many thanks, Herr Springer.

RS

I have expressed the wish that “panta rhei” should be engraved on my tombstone. I think that that is a very apposite statement about life as a whole and about everything that one experiences and what we experience together. I thank you, too.

Photo: Jan Bauer, Berlin

Courtesy Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin