Archiv Charlotte Posenenske

Zwischen Malerei und Relief

3 MAY until 26 JUL 2025

Opening – 2 MAY 2025, 6-9 pm

At Wilhelm Hallen

Archiv Charlotte Posenenske

Photo byAndrea Rossetti

Palette-Knife Paintings – Gesture and Structure on the Surface

Posenenske’s artistic starting point lies in the so-called “Spachtelbilder” (palette-knife paintings) of the late 1950s, created on paper or fiberboard. She applied thick paint using a palette knife, often in muted tones—black, gray, earth colors. Despite the seemingly expressive technique, the compositions are controlled, clearly structured, often with an almost architectural quality. Her focus was less on subjective expression in the vein of Art Informel, and more on the investigation of surface, rhythm, and order. This balance between gesture and structure laid the formal foundation for all her subsequent work.

Adhesive Tape Works – Serial Order Replacing Painterly Gesture

In the early 1960s, Posenenske made a decisive break: she abandoned painting and began working with industrial adhesive tape, applying it systematically to paper or cardboard. These adhesive tape works reflect a conscious withdrawal of the artist’s hand. The painterly gesture of the earlier works is replaced by a serial, constructive visual language. Yet the interest in rhythm, repetition, and structure remains. These works mark a shift toward a more objective and systemic form of practice.

Paper Reliefs – Transitional Forms Between Gesture and Industrial Aesthetics

The paper reliefs represent a pivotal transitional stage in Posenenske’s artistic development. Here, she begins to expand the picture plane into physical space. By folding, creasing, or layering paper and then spraying it with paint—typically in two tones, applied unevenly—she creates sculptural forms with soft color transitions and a vibrant surface. Although the spray technique suggests an industrial process, the irregularities and color gradations retain traces of gestural expression.

Formally and conceptually, the paper reliefs are closer to her palette-knife paintings than to her later modular works. They are not serial components but autonomous pictorial objects—more like paintings in space. Their significance lies in the way they open the pictorial surface toward spatial articulation, while still preserving a visible artistic intervention. The expressive qualities of the early works are transformed but not erased.

Archiv Charlotte Posenenske

Photo byAndrea Rossetti

Series B – Objectivity, Modularity, and Social Openness

With the metal reliefs of Series B, Posenenske reaches a radical turning point in her work. These consist of industrially manufactured sheet metal elements that can be assembled and rearranged in various configurations. The works are not conceived as unique objects but as open systems—potentially infinitely reproducible, anonymous, and collectively handled. The artist’s hand disappears entirely. In its place emerges a democratic, socially oriented conception of art that resists exclusive aesthetics and institutional fixation.

Series B—and similarly, Series A—stands for a form of art that is no longer self-contained, but open to change, participation, and shifting contexts. The earlier gesture is now fully absorbed into industrial clarity and structural openness.

Development Without Rupture

Despite the apparent differences between palette-knife paintings and metal reliefs, a deep internal continuity runs through Posenenske’s work. The principles of structure, rhythm, and repetition, already present in her early paintings, unfold across different levels: from surface to space, from the individual to the collective, from the object to the process. Her paper reliefs represent a crucial step in this progression—not modular systems, but sculptural images that carry within them both the gestural legacy and the industrial future of her work.

Posenenske’s artistic trajectory is not only formally compelling but also reflects a profound reflection on art, society, and production. She demonstrates how expression and clarity, gesture and system, subjectivity and anonymity need not be opposites, but can instead productively inform and transform one another.

Sylvie Fleury

Chew On This

3 MAY until 26 JUL 2025

Opening – 2 MAY 2025, 6-9 pm

At Wilhelm Hallen

Sylvie Fleury

Photo by Andrea Rossetti

Sylvie Fleury’s work delivers coolly composed yet sharply pointed commentary on the limitations of traditional art historical categories and the mechanisms of artistic production. She reveals how seemingly objective systems—like the concept of the canon—are built on structural exclusions and narrow definitions. Through appropriation, shifts in context, and ironic twists, Fleury exposes these underlying patterns. She borrows the visual language of established art movements—often led by male figures—reinterprets it, and invites critical reflection: CHEW ON THIS!

Sylvie Fleury

Photo by Andrea Rossetti

Her monumental installation Center of Excellence (2002) also pushes back against conventional ideas of how space is defined in art. Instead of using heavy metal structures like those of Richard Serra, Fleury suspends flowing sheets of shimmering satin from the ceiling. This textile sheen gives the space a quiet monumentality. Softness replaces hardness, fluidity replaces fixity—challenging traditional associations between form, power, and masculinity.

Fleury also adopts in her series You Too Martin the conceptual visual language of Martin Barré, especially through the use of reflective surfaces that dissolve the boundary between the artwork and the viewer. Here, the image no longer exists solely within the object, but emerges in the moment of encounter—through reflection, movement, and the viewer’s own self-perception. In doing so, Fleury shifts focus from traditional, authoritarian image-making—long dominated by male painters—toward a more equal, self-aware experience. She replaces the canvas with a surface that not only mirrors the viewer’s appearance but symbolically asserts the presence of female artistic authorship. The mirror becomes a projection surface for rewriting art history—toward visibility and recognition of women in art.

In one of her early conceptual, text-based works, Fur Fetish, The Silver Screen Survey (1997), Fleury types film titles onto tissues, noting scenes where actresses wear fur—like Sybil Shepherd in The Lady Vanishes, with the comment: “a Silver Fox Coat (very long).” These titles were collected from an online forum, forming a pseudo-scientific archive of female-coded imagery. Again, Fleury flips an entire artistic language—this time the conceptual practices of artists like Robert Barry, Joseph Kosuth, or Ian Wilson—into its opposite: the emotional, sensual realm of popular film culture.

Sylvie Fleury

Photo by Andrea Rossetti

Sylvie Fleury

Photo by Andrea Rossetti

From the very beginning, Fleury has embraced subversive strategies that diverge from traditional feminist codes. Her deliberate choice to foreground pleasure, luxury, and surface—rather than suppress them—becomes a gesture of empowerment, a declaration of freedom that resists the rigid conventions of the art world.

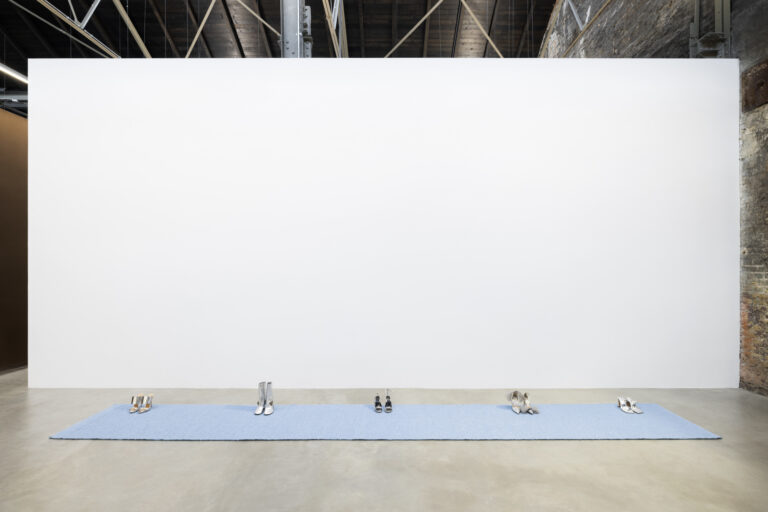

When Fleury explores the fetishized allure of luxury goods, she also dissects the social and economic power structures behind them. In Untitled (No Man’s Time) (2024), she arranges five pairs of silver high heels in a row on a woven carpet, evoking the hallway of a luxury hotel where guests leave shoes outside their doors for cleaning. Here, Fleury reveals the hidden systems at play—the promise of comfort built on invisible (often female) labor—and exposes the hierarchies embedded in the privilege of being served.

Since the late 1990s, Fleury has collected dog toys in Japan. Enlarged and grotesquely transformed, these figures—like the hybrid bird-creature Godzilla Dog Toy 3 (Crazy Bird) (2000)—become surreal witnesses to the mass production of standardized consumer aesthetics. By exaggerating them, Fleury exposes the absurdity of consumption.

–Juliet Kothe

Sylvie Fleury

Photo by Andrea Rossetti

Sylvie Fleury & Angela Bulloch

The Art of Survival/Baby Doll Saloon

3 MAY until 26 JUL 2025

Opening – 2 MAY 2025, 6-9 pm

At Fasanenplatz

Sylvie Fleury & Angela Bulloch

Photo by Andrea Rossetti

Im Zentrum der intuitiven und fast experimentellen Zusammenarbeit von Sylvie Fleury und Angela Bulloch, wie sie die Ausstellung THE ART OF SURVIVAL/ BABY DOLL SALOON in Charlottenburg nun zusammenfasst, stehen Feuerwerk-Performances, die Bulloch und Fleury 1993 in London, 1994 in Dijon und 1999 in Berlin abfeuerten. Anstatt am Firmament als funkelnder Schauer zu explodieren, schienen hier Raketen im Raum detoniert zu sein. An den weißen Wänden bezeugten Schmauchspuren die pyrotechnische Aktion. Dieser Angriff auf das Innere – symbolisch seit jeher aufgeladen als Ort des Häuslichen und Begrenzten – lässt sich als noncharlante Kritik an einer ikonischen Bildsprache lesen, die über Jahrhunderte weibliche Figuren in Interieurs verortete: etwa in Johannes Vermeers Pitzenklöpplerin (um 1670), in den impressionistischen Werken Berthe Morisots oder in Edgar Degas’ Bügelnde Frau (1887).

Sylvie Fleury & Angela Bulloch

Photo by Andrea Rossetti

In ihrer zweiten gemeinsamen Ausstellung 1999 bei Mehdi Chouakri in Berlin (wie 2025 auch in Kooperation mit der Galerie Esther Schipper) zeigten Bulloch und Fleury die Installation A Donut in Paris (1999). Zwei Soft Sculptures begegnen sich: ein erschlaffter Donut von Bulloch und eine kollabierte Rakete von Fleury. Die Formen sind unmissverständliche Geschlechtsmetaphern: Die Rakete – phallisches Symbol par excellence – hat ihre Spannkraft verloren, die Männlichkeit ist entleert. Die als Donut maskierte Frau ist einfach nur erschöpft.

Die Ausstellungen bei Mehdi Chouakri, die dem Publikum die gemeinsamen Arbeiten von Bulloch und Fleury wahrscheinlich größtenteils neu vorstellen, beinhalten Werke aus über drei Jahrzehnten. Bild- und Dokumentationsmaterial wird dabei von den Künstlerinnen teilweise neu arrangiert. So verknüpft eine filmische Collage Aufnahmen der Feuerwerks-Performances mit Stills aus dem dreiminütigen Kurzfilm Should I Stay or Should I Go?, den die Künstlerinnen zu Beginn ihrer Kollaboration im Trocadero, einem Shoppingcenter mit Entertainment-Bereich unweit des Piccadilly Circus, beim Videokaraoke aufnahmen.

Gerade heute, in einer Zeit, in der Kategorien und Klassifizierungen wieder zu Machtinstrumenten werden, lohnt es sich, die Fragen, die Fleury und Bulloch damals und heute spielerisch und intuitiv formulieren, neu zu stellen – und endlich ernst zu nehmen.

–Juliet Kothe

Sylvie Fleury & Angela Bulloch

Photo by Andrea Rossetti