Paula Modersohn-Becker

Paula Modersohn-Becker, Seated girl, its head resting on the right hand, around 1903. Courtesy: Kunsthandel Wolfgang Werner. Photo: Jürgen Nogai, Bremen

A great simplicity of form is something marvelous. As far back as I can remember, I have tried to put the simplicity of nature into the heads that I was painting or drawing. Now I have a real sense of being able to learn from the heads of ancient sculpture. What grand and simple insight went into their creation! Brow, eyes, mouth, nose, cheeks, chin, that is all. It sounds so simple and yet it’s so very, very much.

Paula Modersohn-Becker, 1903

Paula Modersohn-Becker, Girl in twilight with checked blouse, 1904. Courtesy: Kunsthandel Wolfgang Werner.

Nowadays, Paula Modersohn-Becker (1876-1907) ranks among the most influential personalities of European modernism around 1900. Her early works are characterized by the lifelike rendering of the model still inspired by 19th century realism. However, by dealing with the works of artists like Cézanne, van Gogh and Gauguin she developed a quite own pictorial language of a radical simplification of form. Alongside Modersohn-Becker’s paintings, characterized by monumentality and two-dimensionality, our exhibition features works by Birgitt Bolsmann, Almut Heise and Rissa – three female artists who consciously place representationalism at the centre of their painting. By doing so, they are part of the movement emerging in the early 1960s and which marks a turning away from abstraction and art informel.

Paula Modersohn-Becker in her studio, Worpswede 1905. Photo: Paula-Modersohn-Becker-Stiftung, Bremen

Installation view Paula Modersohn-Becker, Kunsthandel Wolfgang Werner, Berlin, photo: anna.k.o.

Almut Heise

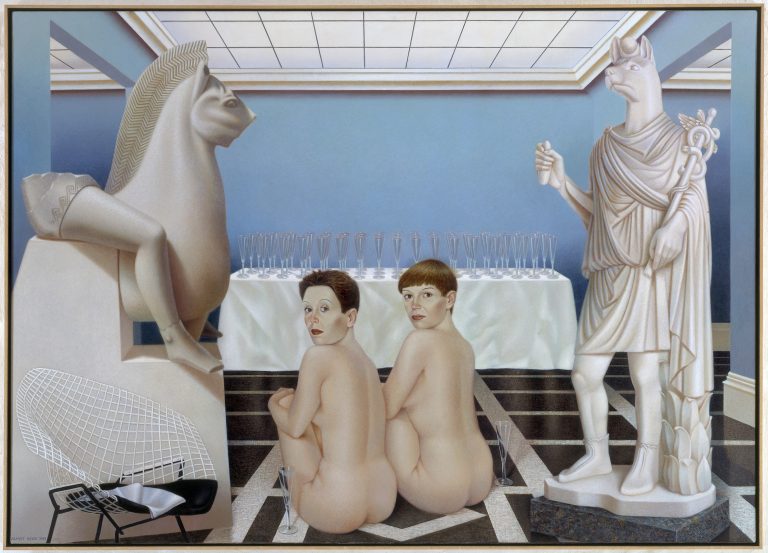

Almut Heise, Large museum scene I, 1989. Courtesy: Kunsthandel Wolfgang Werner / Almut Heise

My pictures are realistic only to the extent that one can believe from what one sees, that things could exist that way. I am not interested in whether it really exists. I want to make one believe it. I want to paint objects and deal with objects and quotations like other people deal with colours and shapes.

Almut Heise

Quite different are the carefully constructed compositions of Almut Heise (*1944). The artist, who studied painting with Gotthard Graubner and David Hockney in Hamburg in the 1960s and with Peter Blake in London (1970–71), received impulses from English Pop Art, but New Objectivity painting and artists such as Balthus or Francis Bacon were also important to her. In her meticulously executed works, Heise depicts interiors along with a repertoire of people in detail. Every fold, every wallpaper pattern and every gesture is tried out until the “longed-for rooms” have emerged. Thus, a painting such as The Great Museum Scene I (1989) dislocates the champagne reception common in a museum context into a cool, surreal-looking scenery by combining, as if on a stage, antique sculpture fragment and plaster copy with two nudes gazing defiantly out of the picture and a design icon of the ’50s.

Almut Heise at the hall of mirrors, Versailles. Photo: Kunsthandel Wolfgang Werner / Almut Heise

Installation view Almut Heise, Kunsthandel Wolfgang Werner, Berlin, photo: anna.k.o.

Birgitt Bolsmann

While studying, I had a close look at abstract art and I noticed that I cannot make use of it to depict the issues that really affect me. I wish to apply a straight visual language, as many people as possible should be able to understand it without turning to an art mediation for explanation.

Birgit Bolsmann, 1988

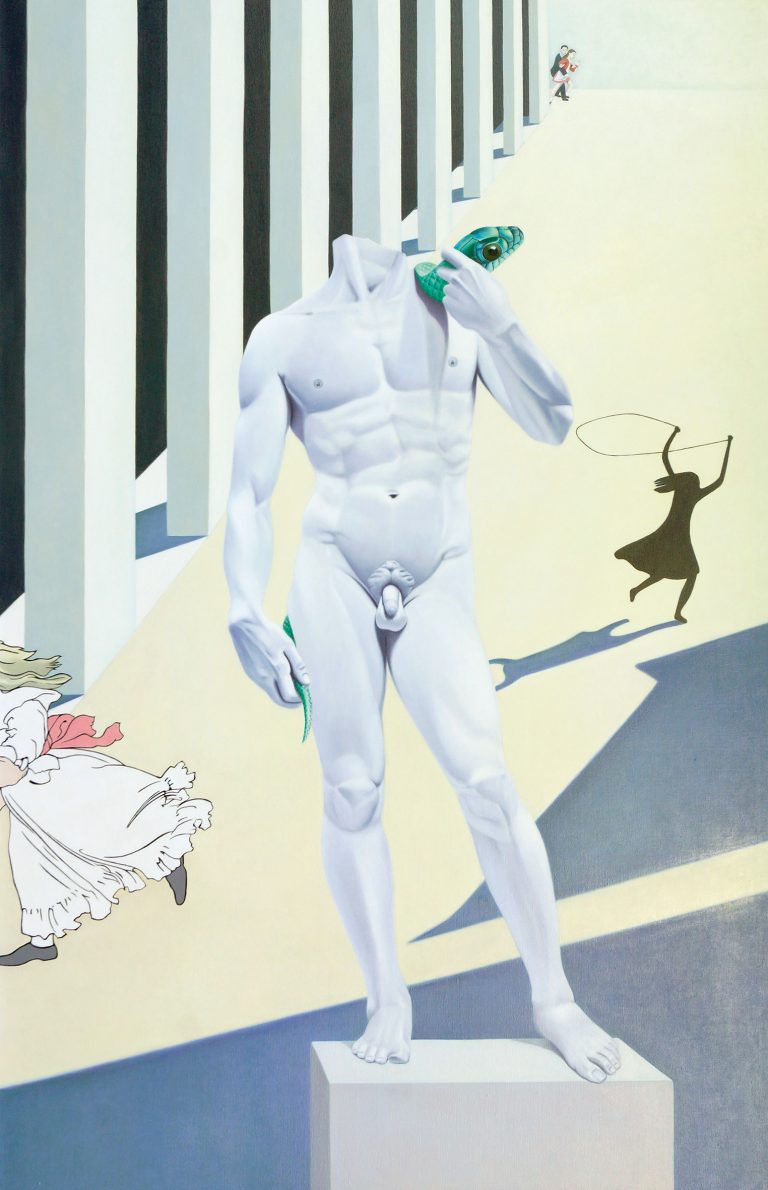

Birgitt Bolsmann, The escape from patriarchy, 1986. Courtesy: Kunsthandel Wolfgang Werner / Kurt Haug (Estate Birgitt Bolsmann), Neumünster. Photo: Angeline Schube-Focke

Installation view Birgitt Bolsmann, Lady with parrots, 1990, Egg tempera, resin oil paint on cardboard, 100 x 65,7 cm, Kunsthandel Wolfgang Werner, Berlin, photo: anna.k.o.

Birgitt Bolsmann (1944-2000) already tried her hand at a reality orientated painting while still studying in Hamburg with Hans Thiemann and Kurt Kranz. She draws her subjects largely from fashion photography and striking advertising, examining them in terms of the image of women that they propagate. In a multi-layered painting process she fixes her subjects with great clarity using a cool colour scheme. The large painting Escape from Patriarchy (1986) reflects her critical view of the male-dominated art world: in a pictorial space constructed à la de Chirico, the ideal of sculpture for centuries, Michelangelo’s David, firmly holds a snake – symbol of the feminine – while two female figures hastily flee this stage.

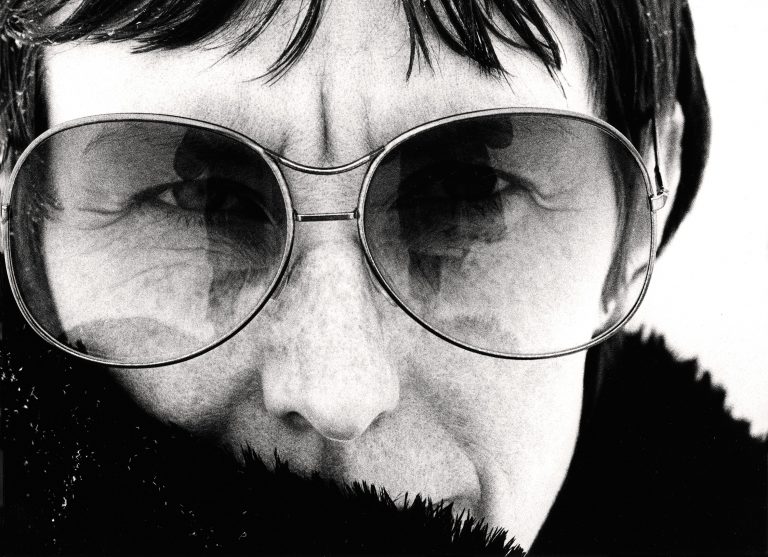

Birgitt Bolsmann on the banks of the Alster, winter 1978/79. Courtesy: Kurt Haug (Estate Birgitt Bolsmann), Neumünster. Photo: Klaus Baum

Rissa

While seeking my own artistic conception, my attention focused on these two dimensions right from the beginning, i.e. on the invention of new form-colour structures as well as on new unusual objective settings or compositions. In 1966, regarding the content, I defined my painting as follows: I wish to depict unusual relationships of objects and actions; they may occur in reality but rarely are they remarked.

Rissa, 1977

Rissa, Skorpion, 1985. Courtesy: Kunsthandel Werner / Archiv K.O. Götz und Rissa-Stiftung. Photo: Raphael Maass

Rissa (*1938), who studied with K.O. Götz in Düsseldorf (1959–1965), decided in 1964, after coming to terms with cubism, expressionism and art informel, on a new kind of figurative painting, which she defined as a synthesis of object-related and abstract approaches. Her pictorial conception is not based on a three-dimensional representation, but on small-scale structures of form and colour, which in juxtaposition produce the contours of the pictorial objects. Rissa’s monumental painting The Large Couple (1980) clearly shows how, in a space without any perspective construction, “snippets of colour” – placed side by side with smooth layers of paint – build up the rhythm of the picture in such a way that the internal forms constitute almost autonomous-abstract plots following a pattern all of their own.

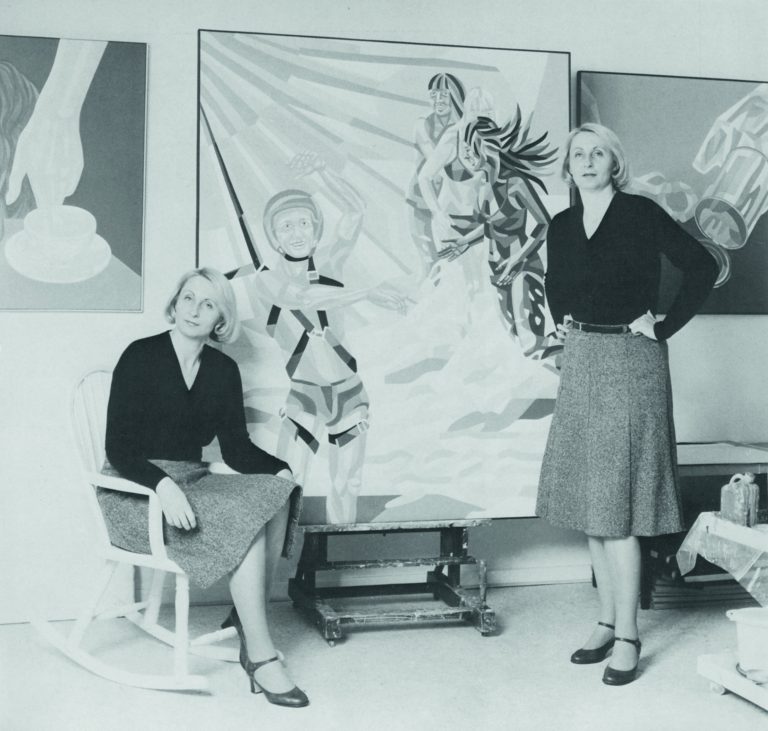

Rissa double portrait, Atelier Wolfenacker, around 1980. Photo: Archiv K.O. Götz und Rissa-Stiftung / Olaf Bergmann

Installation view Rissa and Birgitt Bolsmann, Kunsthandel Wolfgang Werner, Berlin, photo: anna.k.o.