Peter Piller

different degrees of completeness

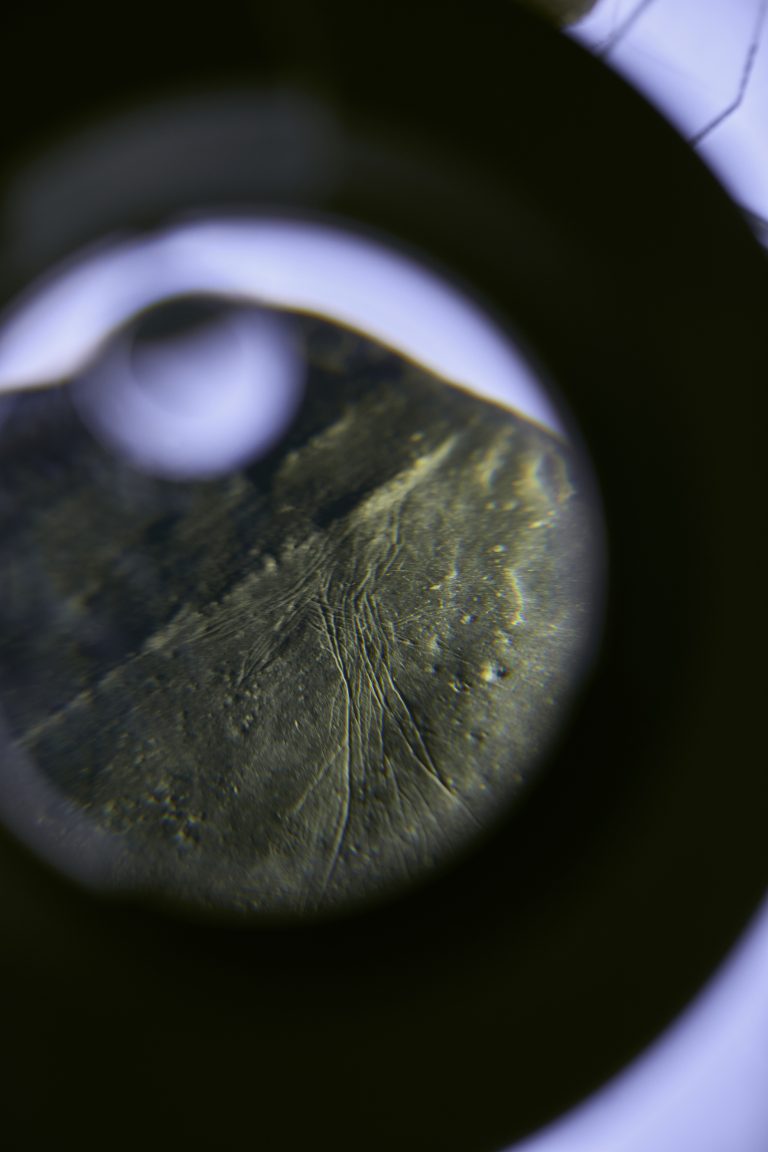

Peter Piller, no title, 2020. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Barbara Wien, Berlin

Galerie Barbara Wien presents its sixth solo exhibition with Peter Piller, entitled different degrees of completeness. Piller shows new own photographs, found images and drawings on a topic that’s interested him since his studies on prehistoric art: How does engaging with Stone Age art change his view onto the everyday world? For years Piller has been exploring the ancient caves in France and Spain, spending time in specialist libraries and scanning illustrations from specialist literature. Here, he juxtaposes magnified reproductions of these finds with his own photographs. For the exhibition, we had a conversation with Peter Piller.

Peter Piller, no title, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Barbara Wien, Berlin

Peter Piller, no title, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Barbara Wien, Berlin

You’ve been engaged with the cave topic, and cave painting, for a long time now. How and when was your interest aroused? And to what extent does it influence the way you view other images, also your archive, your photos, and drawings?

my interest was aroused in the old millennium when i was studying. whilst looking for drawings related to my style of drawing, i came across a book in a library which depicted what could be seen on the walls of a cave. and everything was drawn – not only the perfectly rendered outlines of various animals, as is famous from lascaux, altamira etc., but also a host of other lines that appeared as if they were searching or as traces of an action. research calls these lines “indeterminate lines”, or at the very beginning, they were known as “parasite lines”.

You mean to say the drawings in the book were rather free memory images, not so much designed to depict something visible but rather to be understood in the context of drawing as action, like your drawings that are part of your everyday life and work. That’s a nice comparison, especially the “indeterminate lines”! So, you’ve been engaged with the topic for a long time now, how did it evolve?

in 1999, i went to the south of france for the first time to look at some caves. about four years ago, my interest was rekindled from elsewhere and in the meantime i’ve visited almost 30 caves – also in spain and portugal. since then, i’ve also acquired several metres of literature, spoken to scientists, and visited specialist libraries. the more i read, the more questions arise – that’s it!

Your first exhibition in which the cave theme played an explicit role was two years ago (Geduld at Capitain Petzel, Berlin). There you brought together photos from specialist literature with drawings and images from your archive – the latter being pictures from newspapers, magazines and books that initially had nothing to do with the topic of cave art.

i’m interested in the interaction between the images i choose. it’s an attempt to bring things together, and in doing so, prompt questions that sometimes lead to useful answers. if something really interests me, whether it’s ornithology or enthusiasm for a good novel i’m reading… in other words, if it’s enthusiasm, and not just interest, then i carry that with me wherever i go.

basically, over the past few years, everything i see is to do with caves. and it’s because everything is also being looked at regarding its possible communication with this enigmatic prehistoric art which we will never understand; we can only speculate about it. i find this challenging and relevant to the present: cautious assumptions, insight through delving into and questioning oneself instead of clear mentally dictated announcements.

in the current exhibition, the focus lies on the photos i’ve taken over the last three years, sometimes whilst travelling, but mostly during everyday life. this is because i looked at them and saw that my photographic gaze, and my being in the world, shows this preoccupation with prehistoric art, even though i didn’t want to or haven’t done it consciously. usually, my intuition is wiser than my planned action.

Peter Piller, no title, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Barbara Wien, Berlin

Is your work partly to be understood as something scientific?

i am not claiming to make any contribution to the scientific discussion, but in the meantime i believe i can make a few suggestions for a better understanding. it is completely alien to scientists, and sometimes even a nuisance, to use images as images or individual images like building blocks, without any reference to the origin or meaning of the respective images.

for me, however, the whole thing is also a personal matter. with all research, i probe myself and always ask: what’s the point? what’s it for? what does it have to do with me and my life? that’s exactly the reason i chose my profession. and the whole thing also questions art, because i think prehistoric art can offer a few answers to contemporary issues in art. but that’s where it gets complicated and dubious – when you talk in such a generalised way about very different places, and especially about periods spanning 20,000 years and more. on a prehistoric level alone: if you want to understand to an extent what that is, you should take time to imagine periods of time, or try to understand the circumstances in which nomadic human communities lived before settling down. every cave i’ve visited has its own history and character.

Your work, photos and drawings, your picture archive and your exhibitions form a good template for conjectures, especially since pictures always keep us more in the dark than texts, whether scientific or literary. The title of your exhibition here different degrees of completeness, describes the dilemma – or better still, joy – of the incomplete, of wanting to understand, of continuing and remaining versatile quite well, doesn’t it?

my collecting was never intended to be complete. unfinished completeness is more lively, more active; it allows for errors and contradictions. when we talk here, it is all incomplete, piecemeal, good will, and effectively has little to do with the impulses fed from different sources which propel one to even do something in the first place, even though it is always unclear whether it will lead to anything. i look at what i’ve photographed – what situations i’ve reacted to with a camera – or i place findings from libraries next to each other, of which sometimes i no longer know what the images even represent, and then i listen to see if i am witnessing a conversation.

Peter Piller (* 1968 in Fritzlar, Germany) lives and works in Hamburg. Currently, he has two solo exhibitions at the Weserburg Museum für moderne Kunst in Bremen: the main exhibition, Peter Piller – Richard Prince, runs until October 31; the cabinet exhibition focuses on his artist’s books and will be open until November 14. The group show Sweet Home, Alone at Schloss Kummerow includes selected works by Piller, running until the end of October.

His recent solo exhibitions include Florence Loewy, Paris (2020); Staatliche Graphische Sammlung München/Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich (2019); Museum Schloss Morsbroich, Leverkusen (2018); Mies van der Rohe Haus, Berlin (2018); Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg (2017, with Jochen Lempert); Kunst Haus Wien, Vienna (2016); Städtische Galerie, Nordhorn and Kunsthalle Nuremburg (2015); Fotomuseum Winterthur and Centre de la photographie, Geneva (2014), amongst others.

He has participated in several group exhibitions, including: Kunsthalle Düsseldorf (2020); Triennial of Photography, Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg; Haubrok Foundation, Fahrbereitschaft, Berlin (both 2018); Kunstmuseum Bonn; 11th Shanghai Biennale; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis and Fondazione Prada, Milan (all 2016). From 2006 to 2018 he taught as Professor of Photography in the department of contemporary art at the University for Graphics and Book Art in Leipzig; since 2018 he has been teaching as Professor of Freie Kunst at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf.