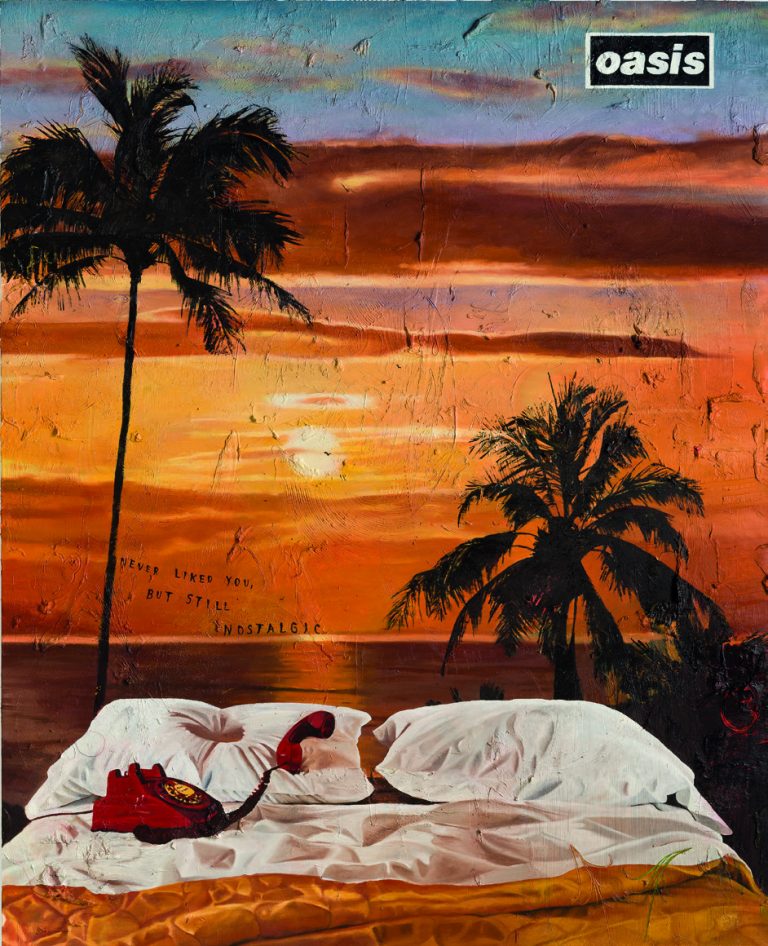

Opposites that attract

An interview with Friedrich Kunath

Friedrich Kunath describes himself as a fanatical Oasis fan and a passionate tennis player. As an artist he paints heartbreaking pictures of romantic longings which often reveal a bitter flip side. In his artworks, his GDR past is as omnipresent as the Californian postcard idyll of his new home. Professionally, he considers himself more a director or composer than a serious painter: He reassembles opposing fragments and lyrics, that in combination, open up new dimensions – between melancholy and irony, love and loss, poetry and politics, Nietzsche and Goofy – and reveals the complex simultaneity and contradictory duality of our lives. Kunath wants to touch us through what touches him. He brings light into darkness, pain into pleasure, and by that, creates the irresistible pull of his colorful paintings, not without humor or self-irony. In a cheerful and profound video call, he told us about the current situation in the US, his creative process, his favorite painting, and spoke very openly about the ups and downs in his life.

© Michael Schmelling

Bettina Krause: What is your mood right now? It is early morning in Los Angeles, right?

Friedrich Kunath: I just arrived at the studio, yes. And I’m not telling you anything new when I say that everything is going of the rails here. America is readjusting, abolishing, or maybe healing itself. That is exciting but also incredibly diffcult.

BK: Do you feel there is room for anything new and good to come?

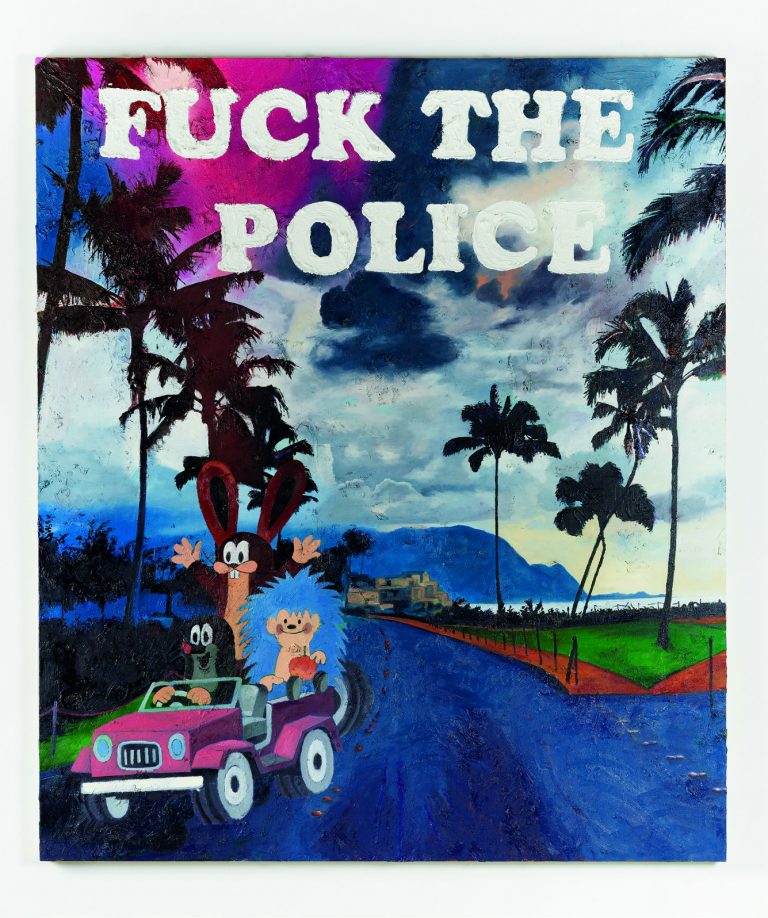

FK: It is all incredibly complex. We are fighting with the pandemic, which has already revealed how riddled the American system is, that the health system does not work. And now we have the social unrest, the culture war. As a white European, I am not qualified to make proposals for America. In Europe, for example, we just don’t know this authority of the police. Right now, I experience America in a state of shock without make-up. It is madness.

BK: How are you dealing with the situation?

FK: I try to get an objective view through non- American media, because here, we have a bit of a problem with a biased media world. But thinking a lot about these troubles, and being an artist, raising children who can’t go to school, and running the household, being in a good mood is quite challenging, currently.

© Michael Schmelling

BK: That is very understandable. I’d like to hear about your upbringing. You were born in Chemnitz – at that time, called Karl-Marx- Stadt, GDR. When did you come to Berlin? FK: My parents separated, and I came to East Berlin with my mother when I was two years old. In 1986, we moved to West Berlin. My mother was in the peace movement at that time, that took place in churches. In the context of this peace movement, some families were “released” to the West, and we were one of them.

BK: At that time, you were 12 years old, so you consciously experienced the GDR, right?

FK: Yes, through the filter of nostalgia, which later also became interesting for my work. My relationship to communism and the repressive model was nostalgized, of course. The more regressive the state is, the larger and closer the community. At that time, we sometimes had 20 friends sleeping on the couch and, for me, it was exciting to grow up like I was in a hippie commune. The deception only became clear in retrospect, when I realized that each of the 20 people who had slept on our couch were Stasi collaborators. As a 12-year-old, in my idyll, I did, of course, not know that. I came with my childish, naive view of the ideal world of communism to West Berlin, where suddenly, everything was lonely. My parents had 9-to-5 jobs and I felt quite sad.

BK: How are these experiences of your past reflected in your work?

FK: In retrospect, it is interesting to see that I always had to deal with two extremes. Two state systems: East and West, capitalism and communism. The extreme euphoria and great sadness, the melancholy. That has been with me since my early childhood. I’m living in contradiction to my history and to myself. That is the red thread from which I have shaped my work. Or the work has formed itself from it and has created an illustration out of these contradictions. For me, as an artist, there was never a search for themes like fellow students at the art academy did. For me, it was always clear what I could report on. The themes are simply there, and the art is always there. I just articulate it. Or it articulates itself.

BK: You studied at the art school in Braunschweig. Where did the impulse for this come from? Did you always want to be an artist?

FK: Not at all. I had difficulties at school and dropped out at 17. I was hyperactive. My mother had a small gallery in Braunschweig for GDR artists. So, art was always there, and music was my other constant. At that time, my mother registered me for a course in experimental painting at the adult education center. There, I made a portfolio in two years: totally naive and great, a mixture of A.R. Penck, Keith Haring, and a bit of Basquiat. My mother sent the portfolio to the art school in Braunschweig without my knowledge. I was invited to the entrance test, but I was 17 and into hip-hop and skateboarding. I was completely overwhelmed and intimidated by the red wine- drinking serious artists at the art school and I failed. The following year, I tried again and it worked out. But I was always an outsider as I was so young, naive and wild.

BK: Walter Dahn had a huge influence on you at that time, right?

FK: Yes, when I met him it was the first time that someone spoke the same language as I did. Through music. Suddenly everything made sense because we explained art to each other through the filters of music history and theory. Walter had his finger on the pulse of time, and for me, he was the key. But, of course, I did not finish university. I did not take a single exam.

BK: How was living in Berlin then, in 1998?

FK: Before that, I had lived a couple of years in Texas because I married a Mexican American woman whom I met on a road trip there. At that time, I had a plan to become a Skateboard pro, but that went all wrong, so I came back to Berlin in 1998. That was the time of occupied houses and illegal clubs. I made hardly any art, was disoriented, had no money, was only interested in parties and drugs. I moved to Cologne to retreat but continued my party life there, and three years later, I ended up with a physical breakdown. With pancreatitis and psychological problems, I almost died. That was a complete cut. Also, my attitude towards work changed completely. Maybe I had just enough “material” to paint pictures, to articulate things by then. However, I threw myself into work, got a show at BQ Galerie, had a successful Art Basel booth, and so my career took of. I was scared, gave up alcohol and drugs – and I got this new life as a gift. And in 2007, I moved to the US.

BK: That sounds like a really tough time. After your breakdown, was it clear to you that you would make art?

FK: It was the only option I had. Before the collapse, I worked at a law firm as a telephone operator and secretly drank beer under the table. That was no life, of course. And once that stopped, I devoted 100 percent of my time to my work as an artist. There was no plan B. The topics for my paintings were there – the disappointment in myself and the euphoria of starting over.

BK: Why did you choose LA as a place to live?

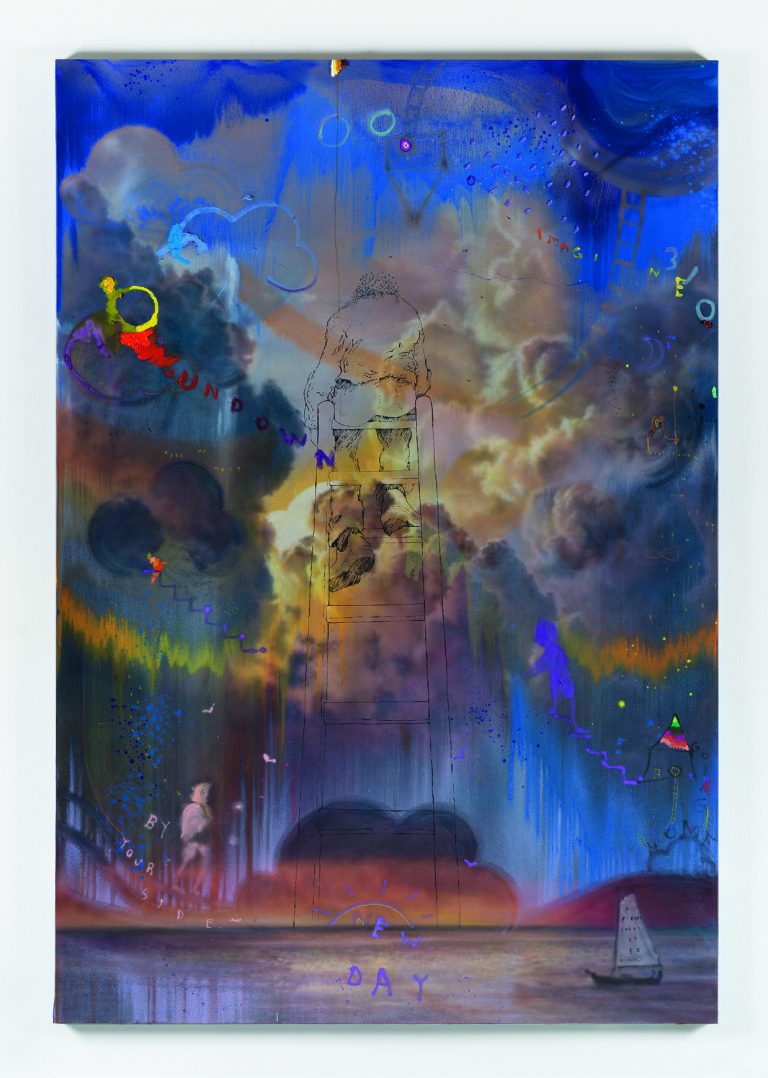

FK: I had this romantic idea of America as a place of longing and that idea of freedom never left me, like a magnet, that was sacred. I found a gallery in LA and I moved. Here, everything was like a huge white canvas without restrictions, very encouraging. I started painting sunsets, without irony. But suddenly, a kind of German romanticism infected an American popular culture in my work and a theater ascended within me, where Nietzsche and Goofy together did something I could only witness. It was extremely interesting because a circle seemed to close itself. And it was a lot of fun.

BK: But it sounds as if the euphoria about America has subsided in the meantime?

FK: Now I am at a point, maybe the catharsis, where I feel melancholy. Maybe also triggered by the crisis, I have a strong connection to Europe again. As if I had eaten too much candy so that I need more radicchio now.

© Michael Schmelling

BK: And Germany is the radicchio, lovely. Is it an option for you to come back here?

FK: I’m thinking about it. My wife and I both grew up under di cult circumstances and our daughter, who is eight, is growing up here in a bubble. It would be interesting to show her European cultures as well. If Trump is elected again, I will actually get a little scared anyway.

BK: You’re welcome to come back any time. Let’s talk about your pictures. How do your paintings come into being?

FK: First of all, I see myself more in the role of a composer or director than a classical painter. I realized early on that I can work best by using things that already exist in our collective library. I was never interested in creating my own worlds of images, but in creating something new from what is there by assembling visual fragments. I was always interested in what happens when you put things together that don’t really t together. It’s like in music, where it’s all about touching people. Music is the most important thing in my life. In a three-minute pop song, someone sings about something existential, personal and creates a projection surface for the listener. For me, that is the most important, most beautiful, and most enlightening thing there is. And all I want to do is reproduce that. That is where I see my task and that’s all I can do. To create something new from these visual fragments – partly knowing, partly not knowing – which, in turn, touches you. Like in a relay race.

BK: That sounds very beautiful. What does it look like in concrete terms?

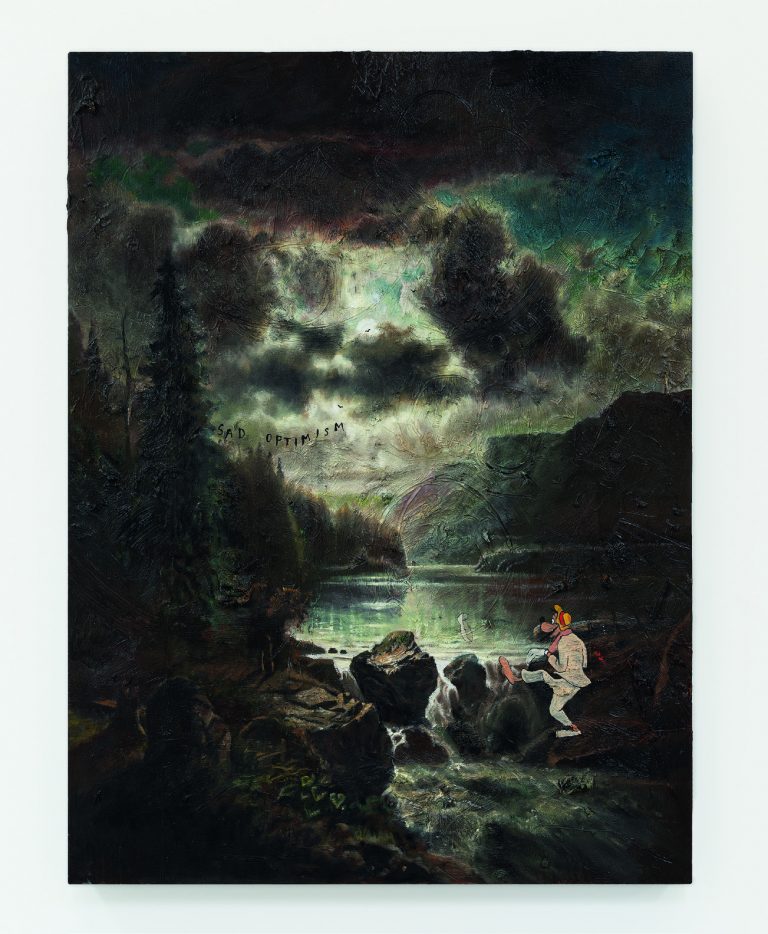

FK: I take something that touches me: a German romantic picture of a dark forest and lyrics, for example, and try to create something out of it. Like sampling, I create stories and illustrate them, create a space with actors who were never supposed to meet each other. Overcoming this impossibility or tragedy – that was always interesting for me. I create a space in the pictures where everything that is not allowed is becomes possible. In doing so, I use recurring symbols, what I call my cast or archive, because it works like the system of a director, like Godard, for example. The actors who haunt my images create a timelessness and reflected naivety – born from complete disconnection. There is no connection between the “Little Mole” and Caspar David Friedrich, but this is exactly what interests me. There is always this almost Tourette-like knowledge that I’m not allowed to bring them together. But I do it anyway and see what happens. As banal as it may sound, I am basically interested in simply passing on what has touched me. Like a good piece of music or a film, which reflects you in your humor but also in your pain.

BK: It says that a good work of art contains the pain as well as it offers the healing. That seems to me to be the case with your work.

FK: I was asked again and again why I paint sunsets and beautiful landscapes. That is because I can only “heal” when I first bring you into the painting, into the idyll, which, however, behaves then like a Trojan horse. I want to lure you into the picture first, and when you’re there, I can still hit you over the head. It’s so easy to paint a bad picture and rely on the radicality of the di cult. That can’t be enough. I always look for poetry, fantasy and lyricism as well. That is more di cult because you are more condemned for it than for the bad painting. It’s always easier to say, “fuck you” than, “I love you”.

BK: Is there a lot of reflection involved when you are painting?

FK: I try to think as little as possible while working. I just want to create an environment in which the picture paints itself, so I am just the medium, like a radio everything flows through. The intellectual work happens before that by reading and discourse. But in creation, the picture is always smarter and further than oneself. When you paint, you give a certain degree of freedom to the picture, which is incredibly reassuring. I start to paint abstractly for hours, almost meditatively. And then I’m interested in what a German painter is not allowed to enter nowadays, the pathos, as the saxophone solo of the ‘90s is impossible today. I really enjoy that, and the romantic is authentic in that moment. What happens afterwards, the irony, is something completely different. When other elements come in, then they may completely change the painting.

© Michael Schmelling

BK: How do you think about all the online art viewings that museums and galleries created during the crisis?

FK: Of course, you always have the digital veil on all that. Everybody is aware that the aura of a work of art, standing alone in front of a picture, the goosebumps, being at the mercy of color, concentration in a museum and total devotion – all this, you can never experience online. But it may be dangerous that the galleries have found that they sell well online, so they no longer need fairs. But fairs are important, especially for young galleries, also to show young artists.

BK: What will you be showing at Gallery Weekend Berlin in September?

FK: There will be a huge bronze sculpture in the middle of the room at König Galerie that picks up on the fact that the gallery space once was a church. It is about political issues and morality and the role of the artist as an outsider. To me, it is important to bring a lot of lightness into this. The show is called Sensitive Euro Man, so it is also a bit self-ironic and reflects the American view on Europe. But I don’t like going to my own opening, actually.

BK: Why not? Because everyone is celebrating you?

FK: On the contrary. It’s that Berlin and Germany have quite a critical view on such things. Not everybody likes what I do. Which is okay, but I don’t think it is an easy position for me to take. If you deal with humor, superficial beauty and clichés, the Germans are skeptical because they still seem to stick to this idea of an artist as a serious character, and as soon as art gets some sort of lightness, they say it is not serious enough.

BK: I hope you’ll be surprised by the reactions on your exhibition. Apart from that event in Berlin, what would be the best thing that could happen to you this year?

FK: That Trump is not re-elected. That they find a vaccine. And that tennis starts again. But most importantly that the Trump madness stops. For Europe too, for the whole world.

BK: Very true. How do you think about hope, what do you hope for?

FK: I don’t really like the term because it implies something passive, a feeling of being at the mercy of someone else. That rather worries me. Hope makes things worse. I prefer certainty. I also hate it when people say, “everything will be okay.” [Laughs]

BK: You just finished your exhibition for the Gallery Weekend. Is it hard to let your paintings go?

FK: Not at all, because the pictures are only finished when someone else sees them. While I’m painting them, I think so much about the person who will look at them that he or she is already part of the process of creation. It only makes sense to me when the picture is received. I want to connect. If you, as a recipient, would not exist, I would not paint the pictures. Other artists see it differently, but for me, it is like this. If I was on a desert island, the last thing on my mind would be to paint my isolation.

BK: That is very interesting, I like that point of view. Do you actually have a favorite among your paintings?

FK: Yeah, If you leave me, can I come too? When I got out of the hospital in 2003, I drew this picture on canvas automatically, as if I was some kind of a “medium”. In retrospect, I know that was the door to a new life, which was black, but it also contained the hope, the prisms. A borderline image. That was, and is, my most important painting because I may not have really painted it myself. Do you know what I mean?

BK: Yes of course, absolutely, I love that painting, too. What happened to it?

FK: It was sold and I had to buy it back myself at an auction. It’s been hanging here with me ever since.

BK: Very good to hear. Would you like to add anything to our conversation?

FK: [Looks at the tattoos on his arms] I’m not that much into tattoos, but here it says, “I don’t worry anymore.” I like this sentence in its idiotic simplicity and also chose it as the title for my book, which is all about my worries. So, I don’t worry anymore. [Laughs]

This article was kindly provided by Zoo Magazine and was previously published in issue No. 67.

Friedrich Kunath’s most recent works will be on display at König Galerie during Gallery Weekend Berlin 2020.