Thomas Struth

Installation view: Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, 3 March – 21 May 2022. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin | Paris | London © Thomas Struth. Photo: def image

Revolving around universal questions of our time with a focus on Science, Nature and Portraiture, three major themes from Thomas Struth’s current bodies of work are shown across the two locations of Galerie Max Hetzler in Bleibtreustraße.

Installation view: Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, 3 March – 21 May 2022. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin | Paris | London © Thomas Struth. Photo: def image

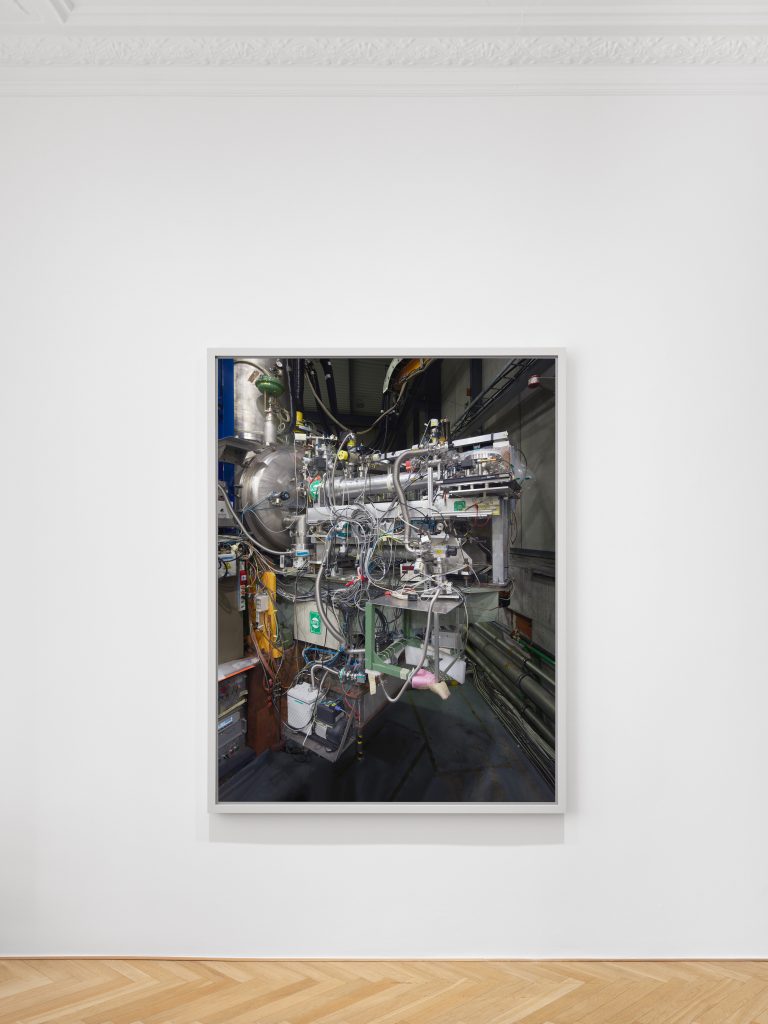

The first-floor space in Bleibtreustraße 45 is dedicated to photographs taken at CERN, the European Organisation for Nuclear Research. The world’s largest scientific facility near Geneva carries out research into the origins of the universe with the help of particle accelerators. Struth’s interest in CERN lies in the philosophical questions, the political dimensions and the pictorial possibilities offered by advanced technology. Do these highly complex conglomerates of cables and valves bear the hope for a better future? The CERN cluster displayed here forms part of Struth’s Nature and Politics, a body of work which he has developed since 2007, examining how ambition and human imagination become sculptural, spatial realities.

Surrounded by the images of technology, the viewer comes across works which deal with nature. A central room is dedicated to a winter landscape entitled Schlichter Weg, Feldberger Seenlandschaft 2021, with an expansive dimension of 220 x 450 cm. The photograph shows a view of an ordinary country road in Mecklenburg, with which Struth has familiarised himself over the last two years of enforced isolation. Themes such as loneliness, mortality and survival resonate in the landscape’s ambiguity. The profusion of branches underneath freshly fallen snow poses similar visual challenges as the view of the equipment in the engine rooms at CERN.

Installation view: Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, 3 March – 21 May 2022. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin | Paris | London © Thomas Struth. Photo: def image

Installation view: Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, 3 March – 21 May 2022. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin | Paris | London © Thomas Struth. Photo: def image

The second gallery space across the street is visible and accessible through wide shop windows. Thomas Struth displays new Family Portraits here, a subject which he has been returning to repeatedly since 1985. More recently, the period of social distancing nurtured the desire to continue working with people. The portraits reveal Struth’s special interest in family life with its psychological entanglements.

Installation view: Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, 3 March – 21 May 2022. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin | Paris | London © Thomas Struth. Photo: def image

Thomas Struth (*1954, Geldern) lives and works in Berlin. Since 1987, Struth has been exhibiting regularly at Galerie Max Hetzler. Major retrospectives of the artist’s work have been recently held at the Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao (2019) and Haus der Kunst, Munich (2017). In 2016, his comprehensive solo exhibition Nature & Politics was inaugurated at Museum Folkwang, Essen, before travelling to Martin-Gropius-Bau, Berlin; High Museum, Atlanta; Moody Center for the Arts, Houston; and finally to the Saint Louis Art Museum, Missouri. Further important solo exhibitions have taken place at international institutions including MAST Foundation, Bologne (2019); Aspen Art Museum (2018); Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2014 and 2003); Kunsthaus Zürich; Museu Serralves, Porto and K20, Dusseldorf (all in 2011); Museo del Prado, Madrid (2007); Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago (2003); Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; and Dallas Museum of Art (2002)

Thomas Struth’s works are in the collections of The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Guggenheim Museum, New York; Tate, London; Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris; Art Institute of Chicago; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin; Kunsthaus Zürich; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; and Dallas Museum of Art, among others.

Günther Förg

EXPOSITION COLLECTIVE 1974 - 2007

Galerie Max Hetzler is pleased to present EXPOSITION COLLECTIVE 1974 – 2007, a solo exhibition by Günther Förg spanning three decades of his career. This is the artist’s twenty-second solo exhibition at the gallery.

Günther Förg’s work was characterised by his multidisciplinary approach, the diversity of thematic references and motifs, and his preoccupation with modernist art and architecture. Since the early 1970s, Förg thus created an œuvre that includes paintings and drawings as well as sculptures, photographs and wall paintings. The mostly abstract and monochrome paintings of the early years are a significant departure from the figurative painting that dominated Germany at the time.

Photos: © Ika Huber and Estate Günther Förg, Münchenstein, Suisse

Examples of Förg’s work, including paintings and photographs (as well as three sketches for Förg exhibitions at Galerie Max Hetzler Cologne from 1983) can be found in the large ground floor exhibition space on Potsdamer Strasse. Förg’s approach to abstract art from a purely formal point of view, albeit with references to modernist art and to the vernacular of art history, allows the viewer to experience a pictorial expression which focuses exclusively on the fundamentals of painting. Looking at the sometimes monumental works, such as a 350 x 1300 cm painting from 2003 or another three-part work from 1998 measuring 260 x 1020 cm, we can see Förg’s interest in an expansive approach to painting which combines individual picture panels with the dimensions and effect of a room. We can see a development in the painting from the monochrome pictures of the 1970s to increasingly structured “window paintings” and, from the early 1990s, to the flickering grids of the paintings known as “grid paintings”. Förg drew new impulses for the continuation of panel painting from the experience he had gained with wall painting. “In the paintings from 1990 onwards, there are sometimes themes and subjects such as window paintings, late paintings by Munch or Bonnard as a starting point, as well as grid paintings or grey paintings that refer to the works of the seventies”.

Installation view: Günther Förg, Exposition Collective 1974 – 2007, Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, 28 April – 6 August 2022. Courtesy the Estate and Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin | Paris | London © Estate Günther Förg, Münchenstein, Suisse. Photo: def image

The many journeys on which, from the 1980s onwards, Förg took photographs, were equally important. He preferred the large format for his architectural photographs. In particular, he devoted himself to buildings of Italian rationalism and iconic 20th century modernist architecture. The photographs are presented with heavy frames, the reflective glass simultaneously reflecting and absorbing space and the viewer. The first house Förg photographed and to which he returned again and again was the Villa Malaparte, which he knew from the Jean-Luc Godard film, “Contempt”, and which the Italian poet Curzio Malaparte had built on Capri in the late 1930s.

Installation view: Günther Förg, Exposition Collective 1974 – 2007, Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, 28 April – 6 August 2022. Courtesy the Estate and Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin | Paris | London © Estate Günther Förg, Münchenstein, Suisse. Photo: def image

Installation view: Günther Förg, Exposition Collective 1974 – 2007, Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, 28 April – 6 August 2022. Courtesy the Estate and Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin | Paris | London © Estate Günther Förg, Münchenstein, Suisse. Photo: def image

A series of bronze reliefs is shown on the outside wall in the exhibition space on the upper floor. Similar to the fleeting application of paint on the heavy supports of the paintings on lead, the bronze reliefs and the sculptures also play with the tension between lightness and weight. The production of the plaster models requires a fast working method, whose expressive handwriting is then effectively frozen in bronze. In the interior of the gallery, a wall painting from 1986 which Förg originally created for the rotunda of the Schirn in Frankfurt can be seen. The wall paintings represent a central aspect of his artistic work. They opened up new presentation possibilities for him, could be combined with photographic as well as painterly works, and were always intended to clarify the space and provide rhythm for its structure. Two torsos standing in the room serve as examples of the sculpture which Günther Förg has added to his oeuvre since the 1980s. The stone casts, one light and the other dark in colour, take up classical forms, but their jagged shape demonstrates his delight in playing with surfaces. In contrast to the smooth wall painting, which is free of any trace of his hand, the expressive gesture is an important feature here. On the end walls of the room, two photographs from the Villa Malaparte replace the windows missing from the gallery’s “white cube”, a device often used by Förg.

Additionally to the exhibition at Potsdamer Straße, the Window Gallery at Goethestraße 2/3 will display Förg’s work Untitled, from 1991 (acrylic on canson).

Installation view: Günther Förg, Exposition Collective 1974 – 2007, Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, 28 April – 6 August 2022. Courtesy the Estate and Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin | Paris | London © Estate Günther Förg, Münchenstein, Suisse. Photo: def image

Jeremy Demester

Djemy

Installation view: Jeremy Demester, Djemy, Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, 29 April – 18 June 2022. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin | Paris | London © Jeremy Demester. Photo: def image

Galerie Max Hetzler is pleased to present Djemy, an exhibition of new works by Jeremy Demester, on view at Goethestraße 2/3, in Berlin. It is the artist’s sixth solo exhibition with the gallery.

In this exhibition, the artist addresses his culture as a Tzigane, specifcally of Kalderash Roma and Sinti origins. The term Tzigane will be used in the following text for clarity purposes; nevertheless, Tzigane people are not a homogeneous ethnic group. There are signifcant nuances in the traditions of each group and family, refected in particular in the wide variations in their respective languages. The artist and his family have written a few words in Kalderash Romanes to introduce the exhibition:

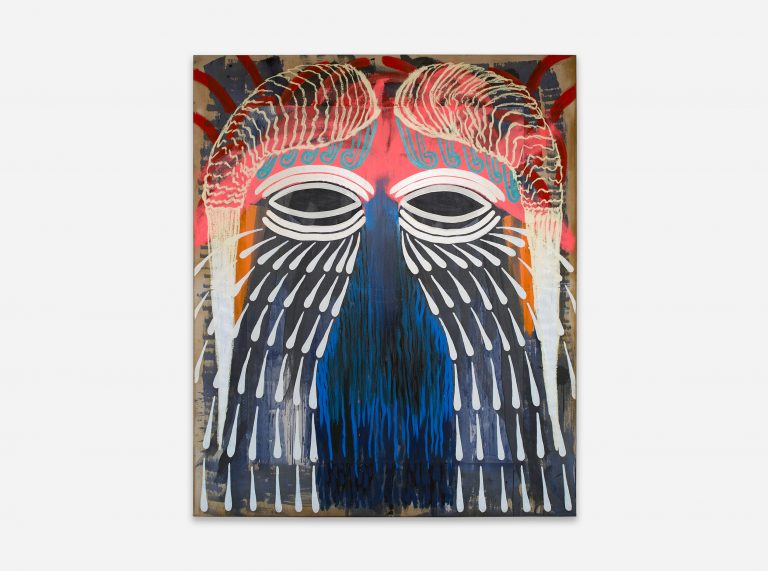

Jeremy Demester, Kalé yaka ké rovén, 2022, oil and acrylic on canvas, 240 x 200 cm.; 94 1/2 x 78 3/4 in. © Jeremy Demester. Photo: Atelier Demester

To li yaka télé,

« Roraves ko roramno pes ané lesko poaré », A djes o mai zuralo Kai rovel anglal savorende, Kanasi baro lanso konik nachtil poutreles, Papirocha vai douano akarel lé gras.

Kana nai tou dan sumnakuné machti poutres o vudar Katar.

Kana roves assoi vai tchorat ké na kel a nétché vouni ai tchorat kanaja langlé machtli avel pal palé,

Chorav eksera ritchya te dikav tu mé.

On the quest to explore his own roots, artist Jeremy Demester has followed the history of the Tzigane people, within Europe to Northern Africa, and onwards, working with a cartographer to draw a map of their known travels and migrations. The title of the present exhibition, Djemy, is his given name in Tzigane language, which uses a plurality of private and public names for a person. Leading on from the research into his own cultural roots, Demester has integrated Voodoo culture into his practice for years, as he lives and paints in Ouidah, Benin, where he established his studio. The artist identified parallels between both cultures, engaging with Voodoo in order to understand his own roots more deeply.

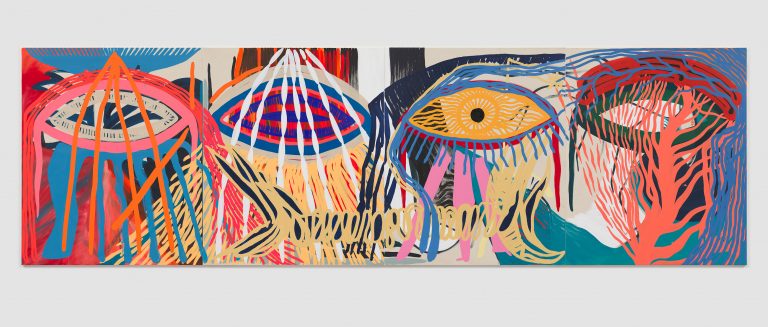

The 15 works displayed in this exhibition are a new body of large-scale portraits, including an ambitious quadriptych unfolding over 8 metres. Some of these images of faces are not simply painted but are completed by the addition of materials such as marble, aluminium, bronze, resin, or carbon, which then form add-on elements such as eyes, ears and braided headdresses, giving the works a sculptural quality. They are mobile, attached to the outside of the original canvas, either by the sides, or above, and strengthen the presence of the works, to the extent that they seem animated. The additional elements are not planned, they are added to the paintings when Demester feels they are necessary for the overall balance. In this regard, he compares his practice to the initial intent of early Renaissance painters such as Fra Angelico (ca. 1395-1455) or Piero della Francesca (ca. 1410-1492), for whom the bas-relief frame of a painting (usually cropped from the images we see in literature), was as relevant as the composition.

Demester’s paintings are portraits of moments, rather than people: ‘[These paintings] are about experiencing how things can be gathered and merged into shapes. To take simple shapes, or just the two eyes, and to build figures. […] They are like portraits of moments, of time. They represent abstractions of the Voodoo and Tzigane cultures coming together. They are portraits of a whole people, a whole dynamic of things. They are protectors and witnesses of situations. […] And a lot of them are crying. They are crying but they are strong.’ Moreover, through his experience decorating temples in Benin, Demester realised that in representation, image has more power than memory. The artist is aware of this immense strength, to the extent of being deeply moved by the paintings while working on them, and sees them as political emissaries, travelling the world from their origin in Benin.

Jeremy Demester (*1988, Digne), lives and works between the south of France and Ouidah, Benin. Demester’s work has been presented in institutional solo and group exhibitions, including at Fondation Zinsou, Ouidah (2021 and 2015); MUba Eugène Leroy, Tourcoing (2019); Stiftung zur Förderung zeitgenössischer Kunst in Weidingen (2018); Château Malromé, Saint André-du-Bois (2018); Mucciaccia Contemporary, Rome (2017); Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain de Saint-Étienne Métropole (2016); Palais de l’École des Beaux-Arts, Paris (2016); and Palais des Beaux-Arts, Paris (2015), among others.

The artist’s work can be found in the collections of Foundation Zinsou, Ouidah; Istanbul Modern; and Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain de Saint-Étienne Métropole, among others.