Mathis Altmann

Butcher Block

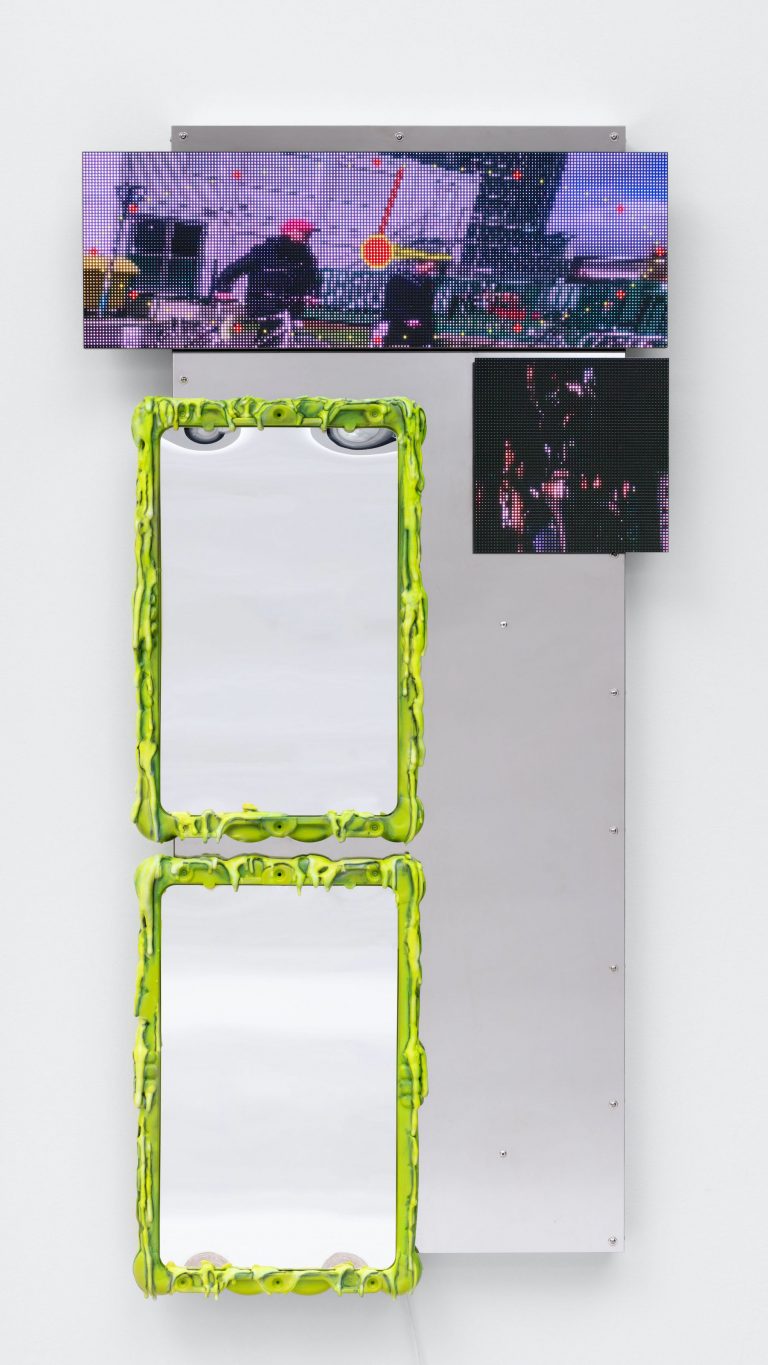

Mathis Altmann, weneverwork, 2021. Courtesy of Mathis Altmann, Fitzpatrick Gallery and Efremidis. Photo credits: Marjorie Brunet Plaza

In his new exhibition Butcher Block, Mathis Altmann (*1987, Munich) witnesses the millennial moment and its ongoing collapse between work and leisure. In the grip of a burgeoning meritocracy, his generation’s drive to improve peaks in a perpetual need for self-glorification.

But improvement is a fraught idea. Though often used in optimistic narratives about technological innovation, the word originally stems from making something ‘more profitable.’ Is there progress in the obsession with advancement? And who can really tell the difference?

Both satirical and introspective, Butcher Block shakes up the co-dependency of contemporary narratives like community, labor, technology and capital. Typically over the top, the artist points toward the agency and complicity of his own generation.

A sweeping portrait of a bourgeoisie sucked into an abyss of its own making.

Darius Sabbaghzadeh, Flash Art

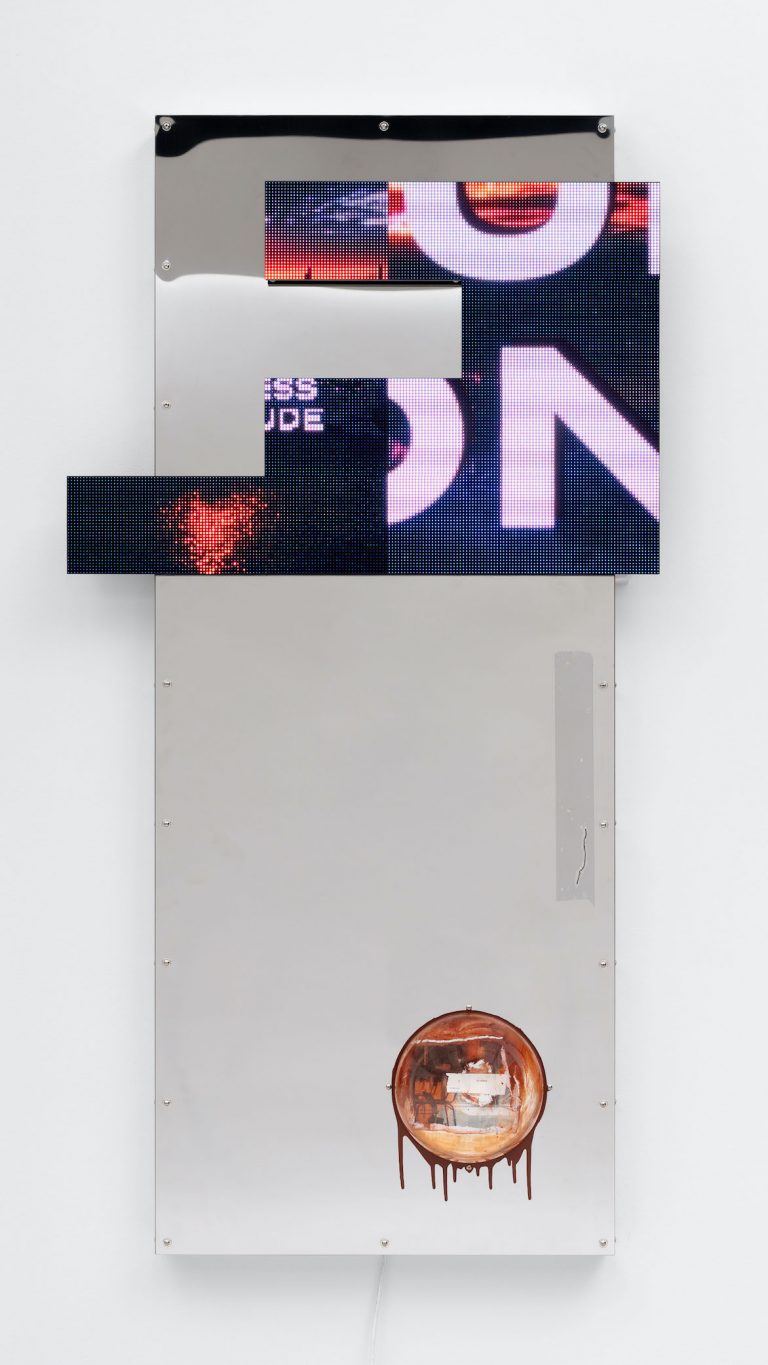

Mathis Altmann, Punch in the face today, 2021. Photo credits: Marjorie Brunet Plaza

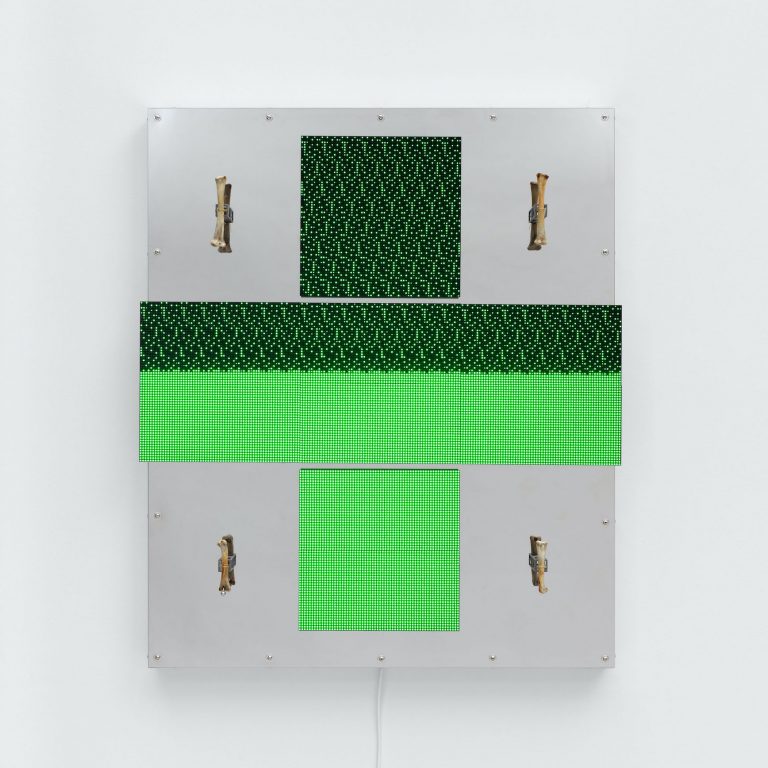

In his new series of LED wall sculptures and illuminated signs, he morphs punk kitsch nostalgia with tech glamour fetishes. Corporeal bodies fragment into pixelation and digitized abstraction. In defense of non-compliance, the artist creates absurd aberrations of the branding strategies of a global co-working company. Defiance is an old dance, showcasing disintegration as some kind of progress. In this Ballardian slapstick comedy, success and failure are superimposed.

Mathis Altmann, Powerlifestyles (versions), 2021. Courtesy of Mathis Altmann, Fitzpatrick Gallery and Efremidis. Photo credits: Marjorie Brunet Plaza

Mathis Altmann, Corpus Oeconomicus, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Efremidis. Courtesy of Mathis Altmann, Fitzpatrick Gallery and Efremidis. Photo credits: Marjorie Brunet Plaza

Altmann’s cyber-baroque objects both suggest and travesty architectural models, public as well as orporate art commissions, agglomerating polar elements and styles: Digital and analog, progressive and decadent, gaudy facades and corroded foundations, all seemingly reacting to a present of pathological contradictions.

Daniel Horn, Brand New Life

Mathis Altmann, Grind to a halt, 2020, detail. Courtesy of the artist and Efremidis. Private Collection Basel

Mathis Altmann currently lives and works in Berlin and Zurich. In 2011, he received a BA from the Zurich University of the Arts, where he has taught since 2016. His work has been shown at Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg (2021); Kunstmuseum Winterthur (2021); The Luma Foundation, Zurich (2020); Mécènes du Sud, Montpellier (2019); Istituto Svizzero, Milan (2018), MAAT, Lisbon (2017); Swiss Institute, New York (2016); Palais de Tokyo (2016); and Halle für Kunst, Lüneburg (2015). He has been awarded the Manor Art Prize (2021), the Prix Mobilière (2016), the Swiss Art Award (2015), and the ZBK Art Award (2013).

Willem Oorebeek

Schmale Anzeige

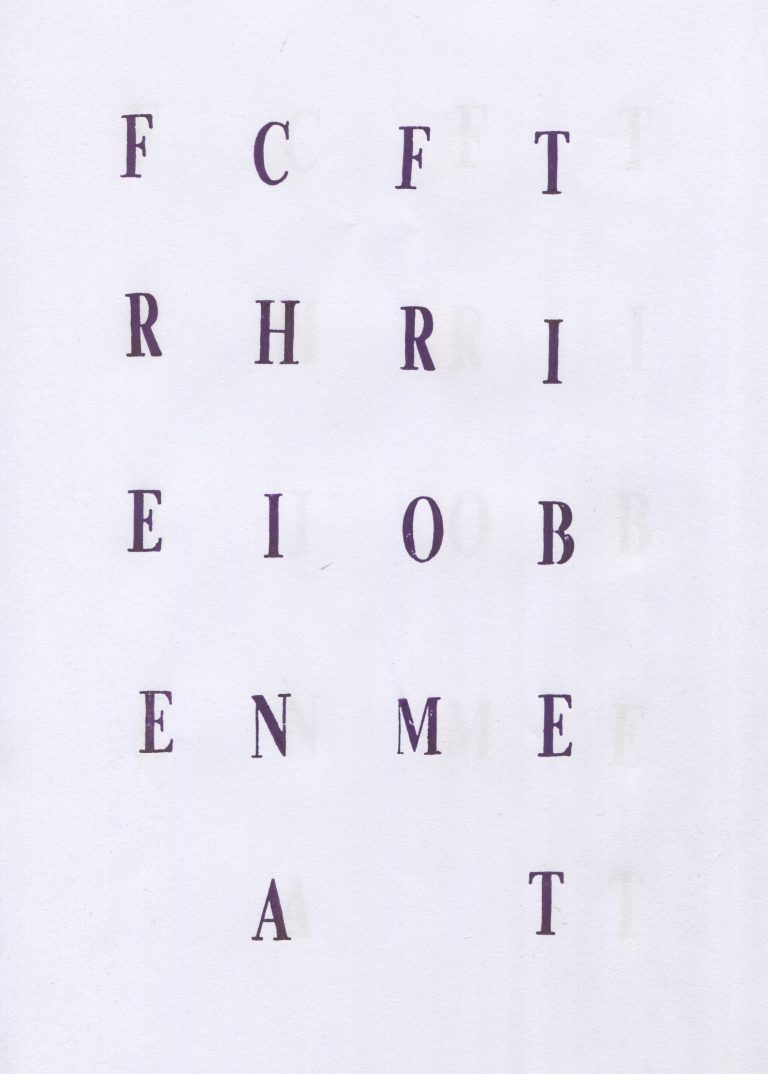

Willem Oorebeek, Anagram, 2020

In his new exhibition at Efremidis, Willem Oorebeek covers the windows of the gallery with the oversized lettering “Free China From Tibet” in a Gothic typeface. The inversion of the popular slogan (“Free Tibet”) demands liberation for the People’s Republic of China and raises the question of what this freedom would mean for the Central State.

Oorebeek’s work positions itself against the backdrop of the present moment in the West in which political rhetoric is escalating and public discourse is becoming increasingly polarized. The desire for total unambiguity and an understanding of a constantly differentiating world cannot be met at the same time. The state of affairs is simply more intricate. The artificial clarity of political slogans inevitably runs the risk of discrediting the legitimacy of opinions.

In addition to the discrepancy between writing and what it wants to refer to, Willem Oorebeek’s work also examines the boundary between image and language. The German calligraphy makes the text difficult to read and creates a tension with the clarity of the printed statements. The illegibility drives the letters from the sphere of language into that of the image.

Oorebeek consistently engages with the medium of print: writing and images are copied, reproduced and torn from their usual systems of reference. Form and content become alienated from one another. The clarity of the original statement is lost and contrasts with the apparent unambiguity of the slogan.

Oorebeek’s work reflects the resulting uncertainty and opens up the possibility of finding a way back to an adequate, more balanced public discourse.

Willem Oorebeek (b. 1953 in Pernis, NL) lives and works in Brussels, BE. Solo exhibitions have to his work been dedicated at the following institutions and independent spaces: Sundogs, Paris, (2018); Yale Union, Portland (2015); Fundação Caixa Geral de Depósitos – Culturgest, Lisbon (2008); Stedelijk Museum voor Aktuele Kunst, Ghent (2006); Ausstellungshalle zeitgenössische Kunst, Münster, with Joëlle Tuerlinckx (2005); Badischer Kunstverein, Karlsruhe, with Joëlle Tuerlinckx (2004) and at Museum Boijmans van Beuningen (1988 and 1996-1999). In 1997, together with Aernout Mik, he represented the Netherlands at the 47th Biennale di Venezia.