Hanne Darboven & Charlotte Posenenske

gallery exhibitions from the 1960s

Opening – 27 APR 2024, 6-9 pm

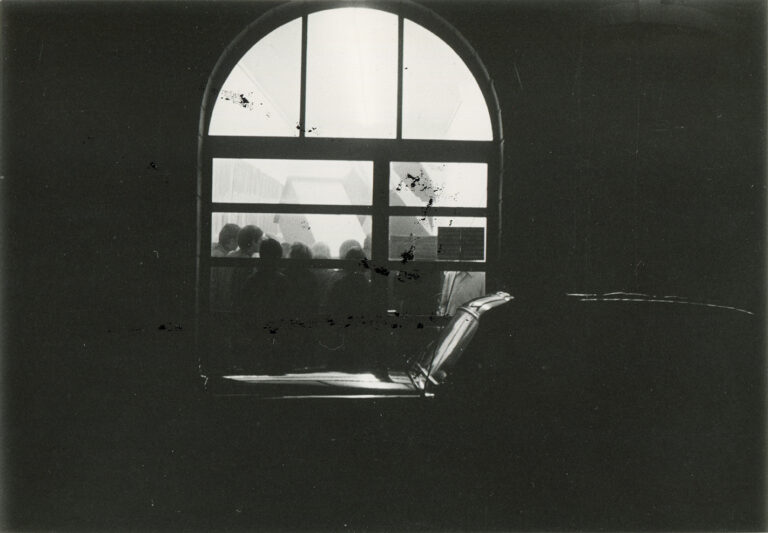

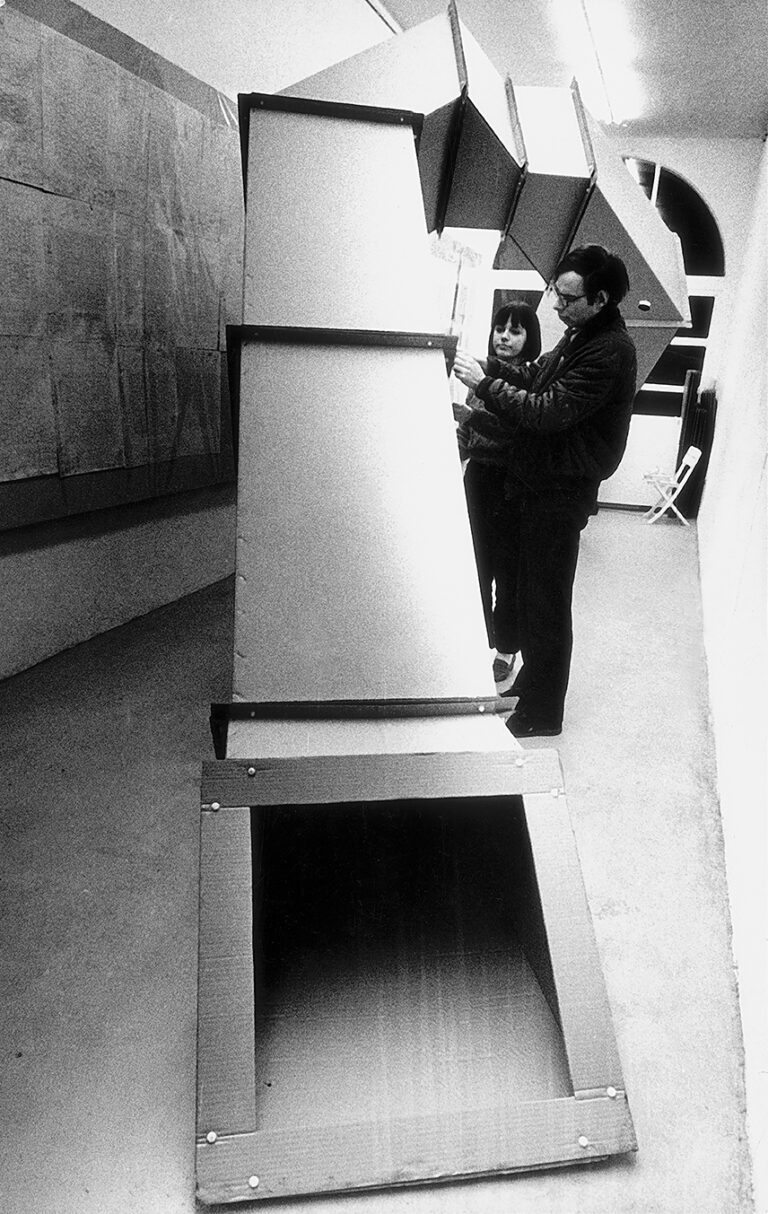

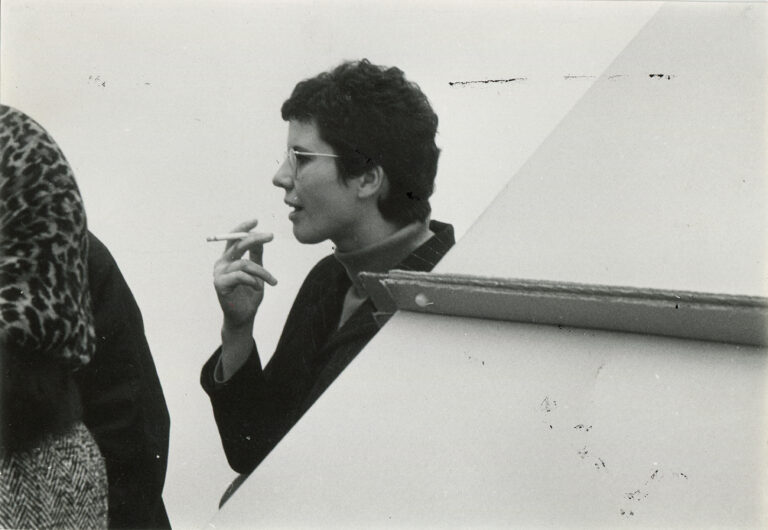

Hanne Darboven & Charlotte

Posenenske, Installation view, Galerie

Konrad Fischer, 1967-1968, Düsseldorf.

Courtesy of the Estate of Charlotte

Posenenske, and Mehdi Chouakri, Berlin.

Die Sachen, die ich mache, sind

veränderlich

möglichst einfach

reproduzierbar.

(…)

Die bisherige Einteilung der Künste existiert nicht mehr. Der Künstler der Zukunft müsste mit einem Team von Spezialisten in einem Entwicklungslaboratorium arbeiten.

Charlotte Posenenske, Statement in: Art International, XII/5, Mai 1968

Four Questions for Paul Maenz

Paul, during the 1960s, you lived in Frankfurt am Main and New York and actively participated in both locations’ art scenes, organising exhibitions and publishing editions. How was the gallery scene in Europe and New York back then, also compared to today?

That could be quite a long story, actually… While New York was an absolute art centre at that time, albeit purely American-focused, the gallery landscape in West Germany still resembled a giant patchwork quilt, with contemporary art struggling to find its way into the public eye. The press hardly mentioned it. Nonetheless, there were passionately run, engaged, forward-thinking, mostly smaller galleries nationwide. It was not until the unexpectedly great success of the newly created art fair “Kölner Kunstmarkt”, which served as a model for the future “Art Basel”, that Cologne emerged as a notable, internationally relevant gallery location.

After returning from New York in 1967, you met Charlotte Posenenske and immediately involved her in two important projects, including “Herzchen…” at Dorothea Loehr in Frankfurt. How did the Loehr Gallery in Frankfurt am Main operate at that time?

Dorothea’s avant-garde gallery – one has to call it that because of its genuinely advanced programme – had experimental value. Always risking commercial success, Dorothea consistently showed the latest and most experimental works. Hence, it was an exciting platform also for Charlotte, whom I had met only a short time before, incidentally thanks to my friend, the artist Peter Roehr. Peter was a frequent, well-informed conversation partner of Dorothea Loehr – so one thing led to another. It was an innovative and productive community that formed against the backdrop of those commercially meagre, less international Frankfurt years.

Courtesy of the Estate of Charlotte

Posenenske, and Mehdi Chouakri, Berlin.

Courtesy of the Estate of Charlotte

Posenenske, and Mehdi Chouakri, Berlin.

Hanne Darboven & Charlotte

Posenenske, Installation view, Galerie

Konrad Fischer, 1967-1968, Düsseldorf.

Courtesy of the Estate of Charlotte

Posenenske, and Mehdi Chouakri, Berlin.

Posenenske occasionally asked you to help her with exhibitions, such as in Hanover and Gießen, writing texts or designing invitations. Was it common for galleries to hand over their introductions and invitations to third parties back then?

Not really; it simply happened that way. Having worked as a designer and art director for an American advertising agency, it was not too difficult for me to visually present artistic concepts in a somewhat appealing and understandable way. Above all, it was a pleasure to work with artists, often in a very practical way – provided that the chemistry was right, of course, and our line of thought aligned. In terms of the content – the “actual” art – there were always fascinating learning processes, which, for example, in the case of Roehr or Posenenske, frequently resulted in quasi-joint practice.

Charlotte Posenenske ended her artistic practice in 1968 and withdrew as an artist, arguably against the background of political and social change in Western Europe. Was her decision also fuelled by the problematic reception of her work by the art market and the institutional setting, by a lack of recognition?

Charlotte publicly stated in her “farewell manifesto” that, as an artist, she was increasingly plagued by art’s “regressing social function” and its inability to “contribute to the solution of urgent social problems”. Far from being a political romantic, she hoped to find answers by studying sociology and in scholarship. Fortunately for us and the future of art, this did not stop Charlotte from standing by her work and guarding it – and, decades later, when she was already marked by an incurable illness, from agreeing to display it in a large exhibition in my former gallery in Cologne. Charlotte Posenenske did not live to see the opening on 11 December 1986. But I think she would have enjoyed this presentation with its expansive arrangement, created at the time with her husband, Burkhard Brunn.

— Paul Maenz (*1939) ran a gallery in Cologne for art of the international avant-garde; he has lived in Berlin since 1992

Hanne Darboven & Charlotte

Posenenske, Installation view, Galerie

Konrad Fischer, 1967-1968, Düsseldorf.

Courtesy of the Estate of Charlotte

Posenenske, and Mehdi Chouakri, Berlin.

Fredrik Værslev

Fredrik Værslev’s curtain bangs

Opening – 27 APR 2024, 6-9 pm

Fredrik Værslev, Untitled (Curtain Bang) #1, 2023, Grundierung, Srühfarbe und Terpentin auf Baumwollleinwand mit Holzbefestigung, 210 x 220 x 10 cm.

Courtesy: Fredrik Værslev, Oslo und Mehdi Chouakri, Berlin.

Foto: Vegard Kleven

For the 20th Gallery Weekend Berlin, Galerie Mehdi Chouakri is showing the

Norwegian artist Fredrik Værslev. Born in 1979 in Moss on the Oslofjord (where Edvard

Munch owned his large country house for many years), Vaerslev is a conceptual and experimental

painter whose work describes an extreme radius of painterly and technical manifestations. Værslev

studied at the Malmö Art Academy and at the Städel in Frankfurt. He is currently Professor of Fine

Arts in Malmö.

In our both gallery spaces — Charlottenburg and Reinickendorf — Fredrik Værslev will be

showing two groups of works in parallel: his “Terrazzo Paintings” and the painterly object series

“Curtain Bang”.

Fredrik Værslev, Installation View

Photo: Andrea Rossetti

Courtesy the artist and Gallery Mehdi Chouakri

Fredrik Værslev, Installation View

Photo: Andrea Rossetti

Courtesy the artist and Gallery Mehdi Chouakri

Fredrik Værslev, Installation View

Photo: Andrea Rossetti

Courtesy the artist and Gallery Mehdi Chouakri

As the title suggests, the “Terrazzo Paintings” appear to be a kind of meticulous reproduction of

the terrazzo floors that are common in homes and kitchens in many European countries. At the

same time, they are reminiscent of the “All Over” of the “Abstract Expressionists” à la Pollock or

Adolph Gotlieb, but also of quasi-representational figurations. In his “Terrazzo Paintings”, Værslev

plays both with the theme of representation and with a random principle of craftsmanship and

painting – in line with their production process: they are created over several months both in the

studio and in the open air, exposed to wind and weather, and thus acquire their own individual

character. The final touch is a narrow, white-gold frame moulding, a deliberately decorative “frame”.

Fredrik Værslev, Installation View

Photo: Andrea Rossetti

Courtesy the artist and Gallery Mehdi Chouakri

Fredrik Værslev, Installation View

Photo: Andrea Rossetti

Courtesy the artist and Gallery Mehdi Chouakri

Fredrik Værslev, Installation View

Photo: Andrea Rossetti

Courtesy the artist and Gallery Mehdi Chouakri

In the second group of works, entitled “Curtain Bang” and shown here for the first time,

the decorative aspect is deliberately thematised and the “curtain phenomenon” is explored in depth,

so to speak: As a utility object with a wide variety of functions, different types and forms, both

upper and lower middle-class, etc. For these curtain objects, Fredrik Vaerslev uses thin cotton,

which is primed and treated with 20 to 30 layers of aqueous paint. Edvard Munch specialist Hans-

Dieter Huber describes this process in his text on the “Curtain Bangs” series as follows: “The

intensive and repeated priming makes the cotton very stiff and heavy. The colour penetrates the

fabric and saturates it as if it were being dyed. It not only adheres to the surface, but becomes one

with the base material. The colour pigments take on an indefinite and transitional quality. Depending

on how you move back and forth in front of the curtain object, it shimmers almost like silk.”

Incidentally, the title “Curtain Bang” reveals Vaerslev’s sense of humour: it also refers to Brigitte

Bardot’s typical and still popular “curtain hairstyle”.

Fredrik Værslev has had solo exhibitions in various European institutions in recent years,

including Astrup Fearnley Museum, Oslo, Kunsthalle Sankt-Gallen, Bonner

Kunstverein, Museo Marino Marini in Florence, Le Consortium Dijon as well as FRAC

Bretagne, Rennes and Haugar Art Museum in Tønsberg. He is preparing a solo exhibition at

the Neubauer Museum in Chicago for 2025.