Archie Rand

Sons

15 NOV until 20 DEC 2025

Contemporary Fine Arts is pleased to present, in cooperation with Max Werner, Sons, an exhibition by New York–based artist Archie Rand (*1949, Brooklyn, NY).

Installation view

Courtesy of Contemporary Fine Arts and the artist.

Photo: Nick Ash.

Archie Rand doesn’t paint single pictures anymore – almost never. He makes groups of paintings. They are not narrative sequences like those we are familiar with from classical European art, such as the life of Christ as depicted by Giotto in the Capella degli Scrovegni in Padua, nor are they series in which a single motif is relentlessly re-examined, as we find in modern painting – for instance, Claude Monet’s paintings of haystacks. And neither do they form a cycle approaching a given topic from diverse angles, in the manner of Gerhard Richter’s October 18, 1977.

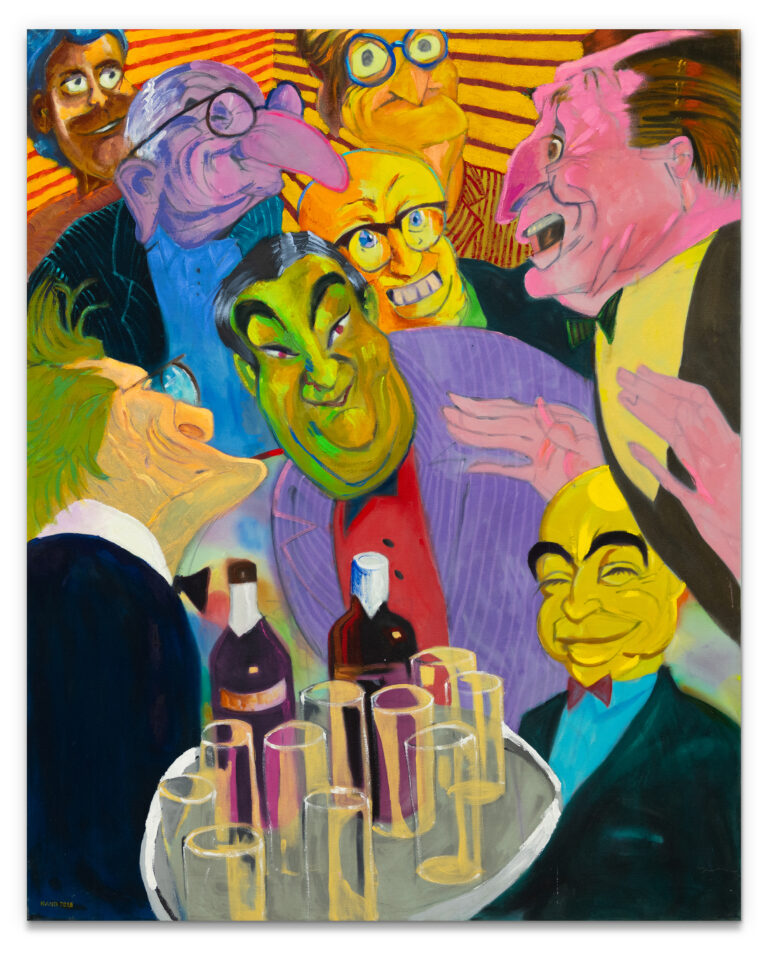

ARR/M 4/00

Archie Rand

“Asher”

2019

acrylic on fabric

152 x 121 cm

59 7/8 x 47 5/8 in

Courtesy of Contemporary Fine Arts and the artist.

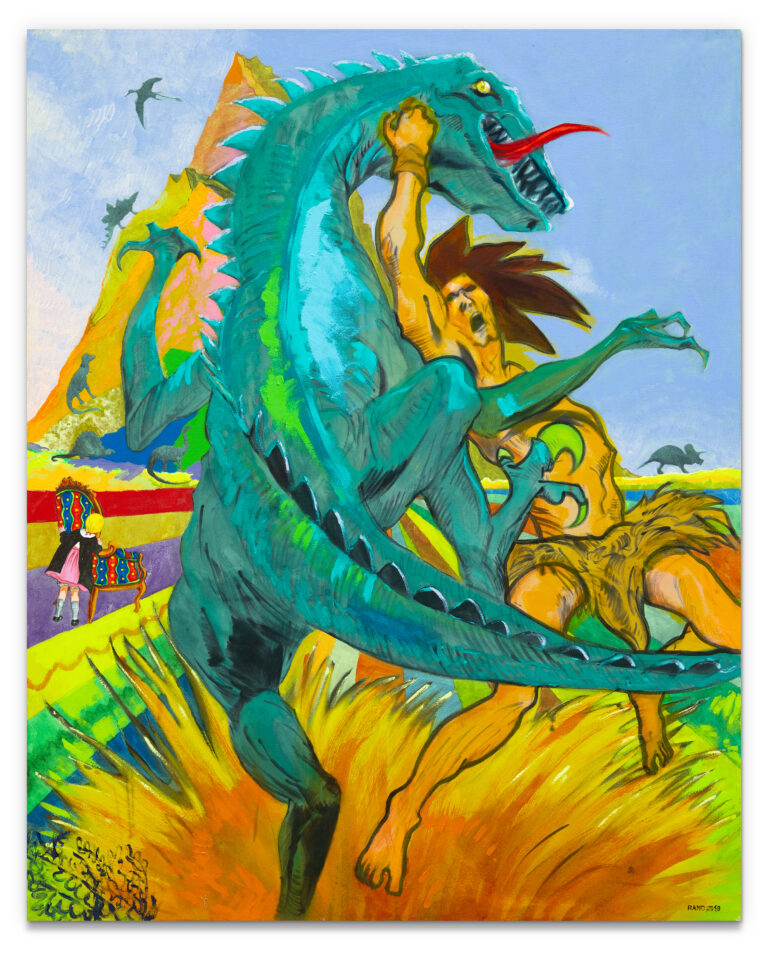

ARR/M 8/00

Archie

Rand

“Benjamin”

2019

acrylic on fabric

152 x 121 cm

59 7/8 x 47 5/8 in

Courtesy of Contemporary Fine Arts and the artist.

Usually, Rand’s groups of paintings are bound to a textual reference – either the work of a modern or contemporary poet or, often, from the Jewish scriptural and exegetical tradition. Most noteworthy among these, so far, has been The 613, 2006. 613 canvases correspond to the 613 mitzvot or commandments given in the Hebrew bible. And yet the texts are not illustrated; the relation between them and Rand’s imagery – raucous, sometimes grotesque, often redolent of early comic books and pulp paperback covers, but with even more lurid colors – is capricious, albeit based on his decades-long immersion in Talmudic scholarhip, which allows him to make metaleptic associative leaps that may not be evident to most of us. As Rand once told me, “The image and text have to have a counterbalance so evenly weighted that you bounce back and forth and it all becomes a song.”1

Rand’s series of twelve Sons has a different origin – not textual but art-historical. In 2018 the Frick Collection in New York mounted an exhibition of a cycle of paintings made in the mid-seventeenth century by Francisco de Zurbarán, Jacob and His Twelve Sons – life-size portraitlike works that detach their subjects from their biblical narratives, though each figure carries objects emblematic of his life and fate as the progenitor of one of the Twelve Tribes of Israel. The paintings are thought to have been intended for a South American destination but somehow, in the eighteenth century, turned up in Britain, where their first known owner was a Portuguese Jewish merchant.

Installation view

Courtesy of Contemporary Fine Arts and the artist.

Photo: Nick Ash.

Inspired by Zurbarán, Rand determined to paint his own cycle about the twelve sons – omitting Jacob, their father. But just as he “did not want to be textually obedient” in his other series, he became a disobedient son to the Sevillian master.2 Instead of depicting the twelve figures in themselves, as Zurbarán did, he would paint, not the sons, but the sons’ dreams. Yes, most of the twelve paintings have a male protagonist – but is that long-haired caveman in hand-to-hand combat with a dinosaur really Benjamin, the youngest of the twelve brothers? We can doubt it. Should we identify Zebulon with that medieval warrior running the other way while the castle wall is being scaled? No. And then there are the paintings with no obvious stand-in for a featured son, most obviously Issachar, whose painting features two cowgirls on horseback riding in opposite directions.

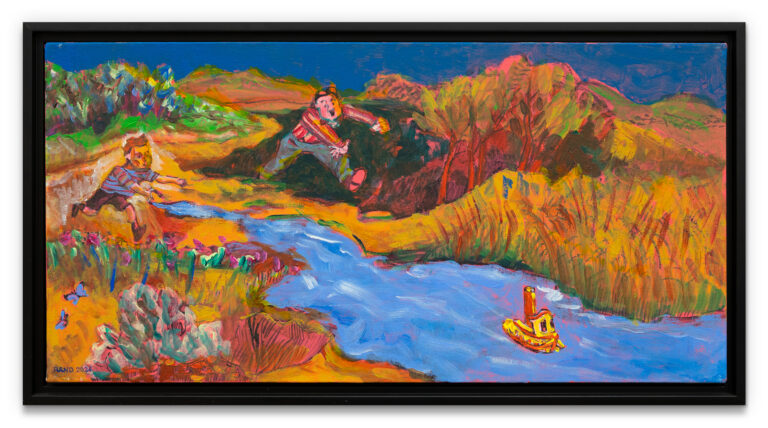

It takes no great leap of the imagination to understand that the twelve sons here are all aspects of one son, namely that of Ruth and Sidney Rand, born in Brooklyn in 1949. These paintings populated by GIs, knights, and cowboys (and the occasional tippling contemporary urbanites who might have come out of a Mad magazine satire) must be what serve as archetypal images in the mind of a child of postwar American urban culture, growing up on Little Golden Books (he was drawn in particular to those illustrated by Tibor Gergely) and EC Comics (Tales from the Crypt, Weird Fantasy, Two-Fisted Tales) – in secret, because comic books were forbidden in the Rand household. All this, remember, at a time when print was still the main medium for the dissemination of images – images whose originals were still mainly drawn or painted by hand. The paintings that Rand conjured from these deeply imbibed sources are profoundly autobiographical without any note of self-portraiture, without any evident diaristic content. They simply pluck from the air whatever still seems resonant, decades later, from the overstuffed memory of what must have been a singularly visually voracious child. For all that, Rand insists that this work is without nostalgia, and also without irony. Regarding nostalgia, I’ll concede the point. He’s not asking us to coo with him over the cute and funny things he loved as a kid. He doesn’t condescend to his young self. In these images are embedded the things he still feels: horror, desire, aspiration, despair. They conjure a world full of obscure anxieties. There is a reason Rand left Jacob – the father of all these sons who in turn became fathers of whole tribes – out of his cycle: These are vulnerable sons, left on their own without protection. Or the protection has been withdrawn, or (more to the point) is felt by the child to have been withdrawn, as when a father pitches his child into the water to sink or swim: “When we have left our father’s arms to be thrown ‘like a stone from a sling’ into the unknown element, there can be no other first impression than bitter hostility.”3 Gaston Bachelard, whom I just quoted, imagined that the deepest images in the unconscious come from the natural world – images of water, of fire and so on. But the sea into which a modern child is thrown is the ocean of images.

ARR/M 28/00

Archie Rand

“Untitled #12”

2024

acrylic on canvas

34.3 x 64.7 cm

13 1/2 x 25 1/2 in

Courtesy of Contemporary Fine Arts and the artist.

ARR/M 23/00

Archie Rand

“Untitled #6”

2024

acrylic on canvas

34.3 x 64.7 cm

13 1/2 x 25 1/2 in

Courtesy of Contemporary Fine Arts and the artist.

As for irony, however, I suspect that Rand and I understand it differently. And why not? There are all kinds. What Rand rejects is the kind of irony that – just like nostalgia – enables personal disavowal. Agreed. But irony can be something more than that. For me, Rand’s art is like what Friedrich von Schlegel wrote of as those “ancient and modern poems that are pervaded by the divine breath of irony throughout and informed by a truly transcendental buffoonery.”4 That last phrase, transcendental buffoonery, is one hundred percent Rand. Irony here means the serene copresence of multiple and apparently irreconcilable perspectives forming a totality. In Naftali, someone’s playing blind man’s bluff in the background while a horseman spurs on a steed that seems to want to turn back, away from the five distant riders who seem to have idly wandered in from a late Degas watercolor. What do these things have to do with each other? In a child’s mind, or the eye of God, they are all one – just not for the rest of us. Our knowing that we don’t know this is what I mean by irony. It’s the name of the song – as Rand’s friend John Ashbery might have said – we know best.5

Barry Schwabsky