Radiate and Fade Away

With works by Lúcia Koch, Anna Bella Geiger and Tarik Kiswanson

1 MAR until 17 APR 2025

Opening – 28 FEB 2025, 6-9 pm

carlier | gebauer, Berlin, is pleased to present the exhibition Radiate and Fade Away, with works by Lúcia Koch, Anna Bella Geiger and Tarik Kiswanson.

Radiate and Fade Away, exhibition view at carlier | gebauer, Berlin, 2025

Photo © Andrea Rossetti

Following Lúcia Koch’s 2023 solo exhibition Light Falls, we are pleased to present a dialogue between Koch, Anna Bella Geiger, and Tarik Kiswanson. Each artist explores the concept of in-between spaces—physical, political, and psychological—that shape our experiences. Together, they question the fixed nature of identity, space, and perception, urging a reevaluation of displacement and fluidity.

In works like Dupla, Koch uses color and transparency to disrupt the functionality of windows, transforming them into objects that no longer serve their typical role of offering a view. Their original purpose—being a passage or opening—is lost, as there is no longer a literal aperture in the wall. Instead, the window frustrates the viewer’s expectation, reflecting them back rather than offering a view into the beyond. The acrylic panes, which shift in color and opacity as one moves around them, create a dynamic relationship between the viewer and the space they occupy. This act of obstruction is not simply a negation of vision; it rethinks how boundaries—both physical and metaphorical—can be altered. The windows cease to act as clear distinctions between inside and outside, becoming instead a portal for an ever-evolving interaction with the environment.

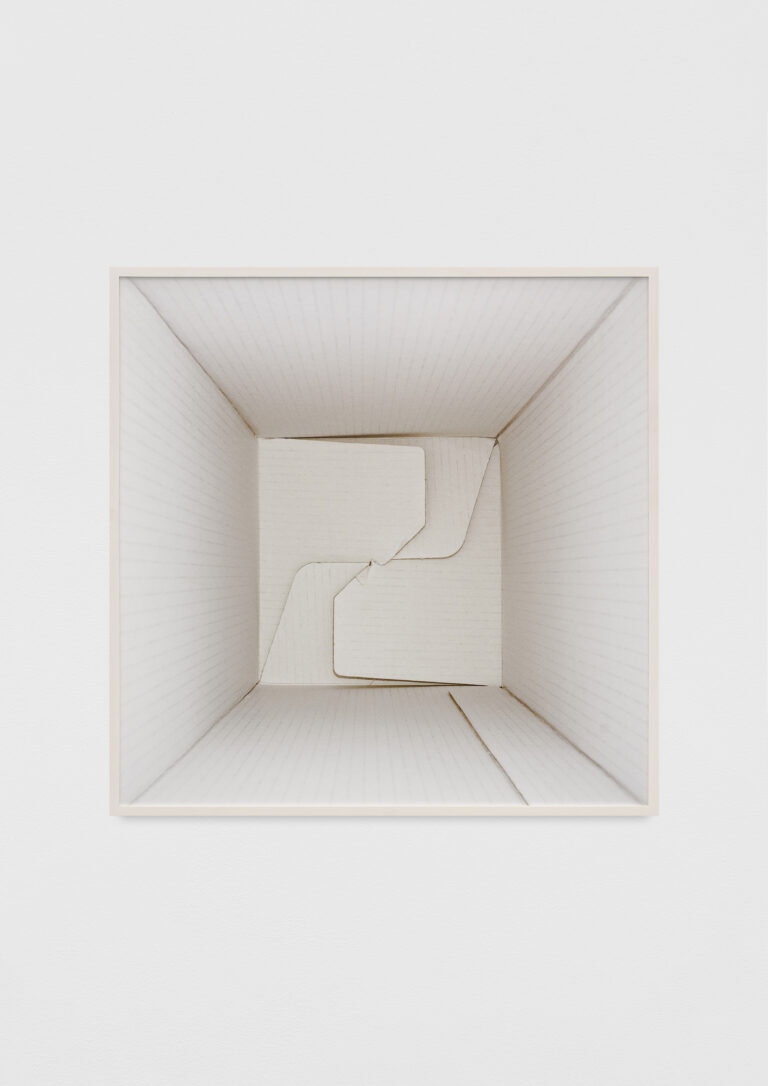

Lúcia Koch

White Cube, 2010

from the series Amostras de Arquitetura

print on cotton paper

70 x 70 cm

Courtesy of the artist and carlier | gebauer, Berlin/Madrid

Photo © Trevor Good

Lúcia Koch

Orátorio, 2013

print on cotton paper

148 x 232 cm

Courtesy of the artist and carlier | gebauer, Berlin/Madrid

Photo © Andrea Rossetti

Koch’s series Fundos further explores this theme by photographing the insides of empty boxes, turning them into uncanny, life-size rooms that appear to extend the space in which they are placed. This play with scale and perspective forces the viewer to question the very idea of space itself: what makes a space inhabitable, and how do our expectations of scale shape our experience of it? In these works, Koch plays with the boundary between the real and the imagined, between architectural structures and the illusions they create. Her work Orátorio, inspired by a visit to the La Tourette monastery designed by Le Corbusier, delves into the tension between light, space, and expectation. What Koch anticipated as a space bathed in divine light instead revealed a dark, vertiginous emptiness. By photographing and manipulating this experience—placing the image at an angle in a corner of the exhibition space—Koch makes it clear that she always installs her works, never simply “hanging” them. She thinks in three dimensions, fitting the piece into the corner, thereby reversing the perspective. In doing so, she challenges the viewer to reconsider the role of light and space in shaping emotional and spiritual experiences.

Geiger has been a pioneering force in the country’s art scene for more than seven decades. A founding figure of the conceptual movement in Brazil, Geiger has long used her art to examine the intersections of politics, geography, and identity. Her engagement with political geography is deeply personal, shaped in part by her intellectual partnership with her husband, Pedro Geiger, a Marxist geographer. Through his theories, Geiger developed a distinctive approach to art that interrogates the nature of maps and territories. For Geiger, maps are not neutral representations but ideological constructs that distort reality. This understanding permeates her work, which often questions how geographical representations are shaped by power and politics.

Anna Bella Geiger

Pier e ocean com favela IV, 1994

oil on canvas

100 x 80 cm

Courtesy of the artist and carlier | gebauer, Berlin/Madrid

Lúcia Koch

Fade away and radiate, 2015

aluminium and acrylic

128,3 x 76,8 x 50,8 cm

Courtesy of the artist and carlier | gebauer, Berlin/Madrid

Photo © Trevor Good

In her series Pier & Ocean, Geiger confronts abstraction through the fragmented space of the canvas, evoking both geographical forms and a sense of emotional dislocation. Dividing the canvas into sections, she engages with the tension between fragmentation and unity, suggesting a world that is constantly in flux. The reference to geographical forms—like an aerial view of islands—suggests a sense of isolation and introspection. Yet, these references remain abstract, challenging the viewer to reconsider the very idea of space and place. Geiger’s work is marked by a constant tension between the personal and the political, the abstract and the figurative. In her earlier series, she used clouds as a metaphor for territories that could be imagined rather than occupied, a gesture reflecting the political repression of Brazil’s military dictatorship. These clouds—like many elements in her work—are not fixed but exist in a state of ambiguity, offering a space for imagination and resistance. This focus on mutable, open-ended spaces speaks to a larger question about the role of the artist in a politically charged context: how does one navigate the terrain between representation, abstraction, and activism?

Kiswanson’s monumental, cocoon-like sculptures explore themes of transformation, shelter, and becoming, resonating deeply with the notions of physical and ideological boundaries explored by Koch and Geiger. Much like Koch’s installations that alter architectural space through light and materiality, Kiswanson’s work challenges the viewer’s perception of space and identity. His sculptures, which evoke natural states of metamorphosis—pupas, eggs, and seeds—suggest a constant state of flux, where boundaries are neither fixed nor stable. These organic forms, which nestle into the gallery’s architecture, blur the line between art and environment, creating a space where transformation is not just a visual experience, but an existential one.

These works challenge the rigidity of space, identity, and perception, urging a deeper reconsideration of the boundaries that shape our realities. Through their diverse practices, Koch, Geiger, and Kiswanson interrogate how physical, political, and psychological spaces are in constant flux, pushing us to question the fixed nature of the world around us. Whether through the manipulation of architectural form, the abstraction of geographical territories, or the metamorphosis of organic sculpture, their works emphasize the fluidity of identity and the power of transformation. In a world increasingly defined by dislocation and fragmentation, their works offer an evolving dialogue that defies static definitions and invites a continual reimagining of space, self, and belonging.

Lúcia Koch (b.1966, Porto Alegre) lives and works in São Paulo; Anna Bella Geiger (1933) lives and works in Rio de Janeiro; Tarik Kiswanson (b.1986, Sweden) lives and works in Paris.

Ian Waelder

cadence

1 MAR until 17 MAR 2025

Opening – 28 FEB 2025, 6-9 pm

Ian Waelder, cadence, exhibition view at carlier | gebauer, Berlin, 2025

Courtesy of the artist and carlier | gebauer, Berlin/Madrid

Photo © Andrea Rossetti

For the ancient Greeks, Mnemosyne, mother of the nine muses and Goddess of memory, symbolized the preservation of knowledge, experiences, and emotions. Memory is encapsulated in our lifetime and all that goes beyond it turn into History. This is a reason why, perhaps, we started looking again at other cultures and traditions and at their rites. For many non-Western cultures memory entails the exercise of going back in history.

Recalling as many traits as possible and details of that past through collective remembering and oral narratives was a way of visualizing together the ancestors, our predecessors. In rural Spain, where I come from, many families like mine celebrate a rite for the grandparents that all family members attend to pay respects in the day that person died.

Ian Waelder

Cadence , 2025

Wooden object from 1999, traces of stains, crumbled inkjet print on paper, foldback metallic clips and sheet of glass

20 x 39,6 x 09,8 cm

Courtesy of the artist and carlier | gebauer, Berlin/Madrid

© Ian Waelder

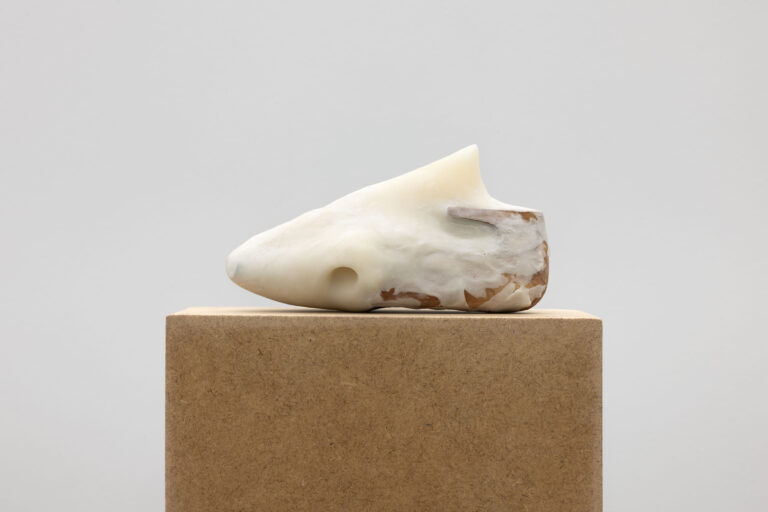

Ian Waelder

Sneaker, 2025

Wooden shoe last, air-dry porcelain, wooden structure

9,5 x 17 x 7,5 cm

Courtesy of the artist and carlier | gebauer, Berlin/Madrid

Photo © Andrea Rossetti

Still our culture is mostly oriented towards the future, a bright future, a future of people that can top the pyramid of tasks and achievements better than others. Our culture has erased, therefore, all spaces defined and designed to honor the past and honor the fact that we are a result of the collective effort of many other individuals in the present and in the past. Niches, chapels built into the exterior walls of buildings, marvelous little boxes containing the image of a saint that are passed from one house to another… all the elements designed to care for and ritualize memory — and the emotions of the past — have vanished. It is true that we spend hours searching for guidance on mindfulness and meditation to find ourselves. But it is also true that no contemporary trend has decided to make us reflect on the living conditions, the mottos for life and the values of those who lived before us. The ancestors have appeared more as a way of positioning and capitalizing on certain features of our present. There is a veritable cascade of books in which only the grandparents speak, but in most cases the authors only use their presence, their lives, to enhance their own. We are little vampires of the past. I felt in love with the writing of Milan Kundera because he described, like no one else, the Western ways of capitalizing eternity.

I think you all will relate to the work of Ian Waelder. In a very steady way, he has been affirming his artistic practice –mostly developing installations, sculptures, sound and films—as the embodiment of a site to remember. Before entering the work of perhaps now, after having been there, think about it as a “site” not as a sculpture and not as an installation. A site is a place as seen through our mind. Here the site Ian Waelder has produced is a three-dimensional logical place defined by the intervention in the space and the sculptures that we encounter there. A site possesses the physical rawness given by the location and the intervention he did in this place and a high level of fictionality or abstract-ness since the place is constituted by a sample of elements and realities displayed to ignite our minds.

Ian Waelder

To Wait, 2025

Plywood, paint, woodfiller, air-dry porcelain, hanger, tissue paper, linen shirt, dry-cleaning plastic bag

148 x 220 x 27 cm

Courtesy of the artist and carlier | gebauer, Berlin/Madrid

Photo © Andrea Rossetti

Ian Waelder

From hip to fingertip (Opel upside down), 2022

Remainder of the acrylic resin mould of the Opel Olympia sculpture made in collaboration between the artist and his father, putty on wall, iron rods and remains of the wall on the floor 33,5 x 35,5 x 30 cm

Courtesy of the artist and carlier | gebauer, Berlin/Madrid

Photo © Andrea Rossetti

The visit to this site will take place –or took already place—alone. This is a very important trait. It is intended to intensify the connection between the place/the work and the visitor. Ian, the artist, has gathered his materials because of a personal experience –his life, his memories, his family memories– but also a consequence of his endeavor of creating a freestanding, seemingly independent body of work. A work that has an ambition to expand the presence and social/collective function of sculpture while, as well, being able to name and identify a range of themes, including time travel, nature, perception in a capitalist industrial society, climate….

His work is very inspiring because it always suggests deep analogies between the presence of the viewer and the structure of the work in addressing love relationships, communication, epoch, and narration. It is a piece that demonstrates that the art practice is the best place to absorb and redefine our emotional social life, our views on time and immortality.

Text by Chus Martínez

The artist would like to thank Isabelle Tondre, Maïly Beyrens Xu; the installation team:

Alexander Denkert, Balthazar Ausset, Filippos Tatakis, Igor Panek, Ralf Rose, Oscar Gebauer,

Xenia Bond; the cg team: Alix Chambaud, Amy Binding, Angela Mewes, Françoise Danthine, Henrike Daum, Jana Hampel, Luis Bortt, Maria Rudy; Marie-Blanche Carlier and Ulrich Gebauer.

Ian Waelder (b. Madrid, 1993) is a Spanish-American artist and publisher living in

Frankfurt am Main and Mallorca. Waelder is the founder of Printer Fault Press, a publishing house and collaborative platform that provides space for the work of fellow artists, curators and writers. He graduated in Fine Art studies from the Städelschule in

Frankfurt in 2023 as Meisterschüler in the class of Prof. Haegue Yang. He was also a student in the classes of Peter Fischli and Mark von Schlegell. He is the recipient of the Kunststiftung DZ Bank Förderstipendium 2023/24 and was resident artist at the WIELS Center in 2024. His work has been exhibited at diez, Liste Basel (2024); Super Super Markt, Berlin (2024); carlier | gebauer, Berlin (2024); Neuer Kunstverein, Gießen (2024), Es Baluard Museu d’Art Contemporani, Palma (2023); Kunstverein Wiessen (2023); Delfina Foundation, London (2023); Fundació Antoni Tàpies, Barcelona (2023); Galerie Rolando Anselmi, Rome (2023); Francis Irv, New York (2023); ethall, Barcelona (2022); Nassauischer Kunstverein, Wiesbaden (2021); L21, Palma (2021), Centro Párraga, Murcia (2018), the Finnish Museum of

Photography, Helsinki (2018), La Casa Encendida, Madrid (2014), among others. His works are part of the collections of Kunststiftung DZ BANK, Frankfurt am Main; Es Baluard Contemporary Art Museum, Mallorca; and Rothschild & Co, Zürich.