Everything Everywhere All at Once

Notes on Eddie Martinez’s Supernature

by Oliver Koerner von Gustorf

An insect is squashed, a dog buried. The first snow falls, plants on a windowsill bloom, a toy is left behind in a parking lot. When we are children, the first existential, all-changing experiences of life, death, time and transience usually do not enter our lives in big, dramatic situations. It is the small, ephemeral moments that don’t really register in the macrocosm of adults that take us across a mystical threshold, making us feel previously unknown sensations of grief, joy, creation and destruction, as well as helping us to see ourselves as part of a greater whole.

Ever since Eddie Martinez had what he refers to as “a wasp nest situation” at his Long Island home in the summer of 2021, the can of Raid bug spray has become a recurring motif in his paintings, appearing in di!erent variations in works such as the titular work of this exhibition, Supernature (2022) and Endangered (2022).

Courtesy the artist and Capitain Petzel, Berlin. Ph: JSP ART Photography

Probably the most famous insecticide in the world, Raid was first launched in the US in 1956, right in the middle of the Cold War, when Abstract Expressionism was the epitome of the art of the free West. The first Raid cartoon commercial, with its popular “Kills Bugs Dead” slogan, was realized by none other than Tex Avery. The plot of these commercials, which were produced for over forty years, always remains the same: dart-nosed mosquitoes, pudgy bugs, and ravenous ants plan raids on the kitchen and the garden where picture-perfect apples and plastic flowers grow. Their exploits are always brought to a halt by the Raid superhero spray can, whose nozzle emits a kind of atomic annihilation ray that sends the screaming insects to kingdom come.

Courtesy the artist and Capitain Petzel, Berlin. Ph: JSP ART Photography

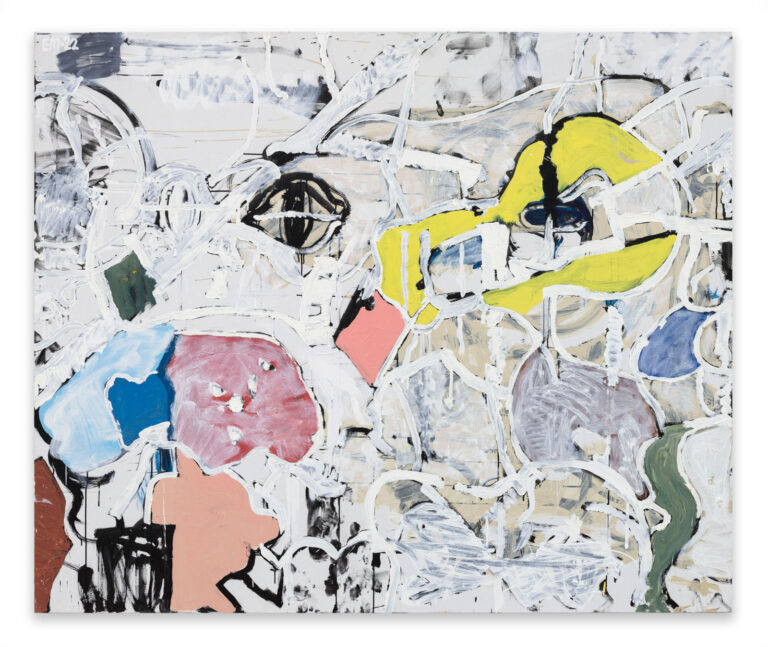

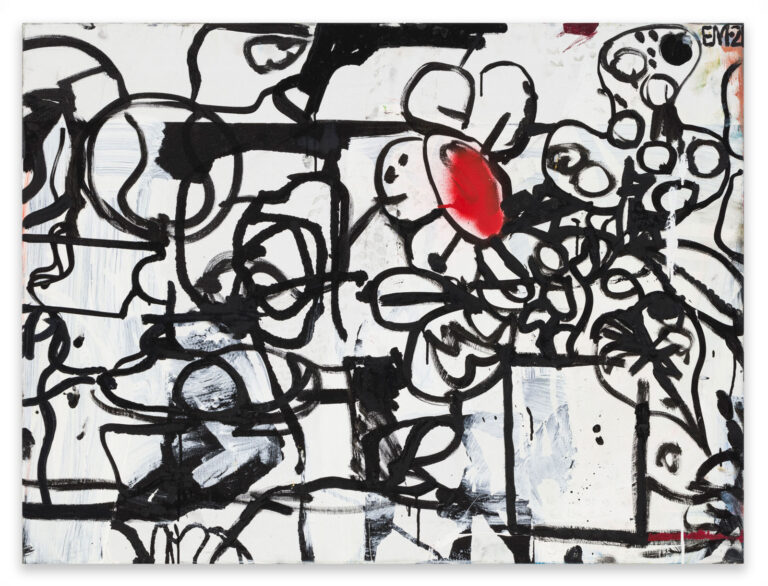

In Eddie Martinez’s Raid paintings, everything is illuminated in a flowing stream of consciousness: the microcosm we discover on a table, in a flower, the undisguised sense of a new, completely fresh experience, cold war, the visual repertoire of Abstract Expressionism and the post-conceptual painting movements that followed in response, the DNA of cartoons from the fifties and sixties, all fused with flashes of the here and now, ephemeral perceptions, the artist’s whole life—everything, everywhere, all at once.

As if in an echo chamber, the gestural abstractions of fragmented cartoon vermin linger; eyebrows left in mid-air, along with potato-shaped bodies, something creepy-crawly, a grin frozen into a line. And then there is the can of Raid, which Martinez boldly scrawls onto the canvas in an ever-changing array of strokes and flourishes. It might be a tank, a cannon, part of a fragmented logo, perhaps a revolver with a finger already on the trigger.

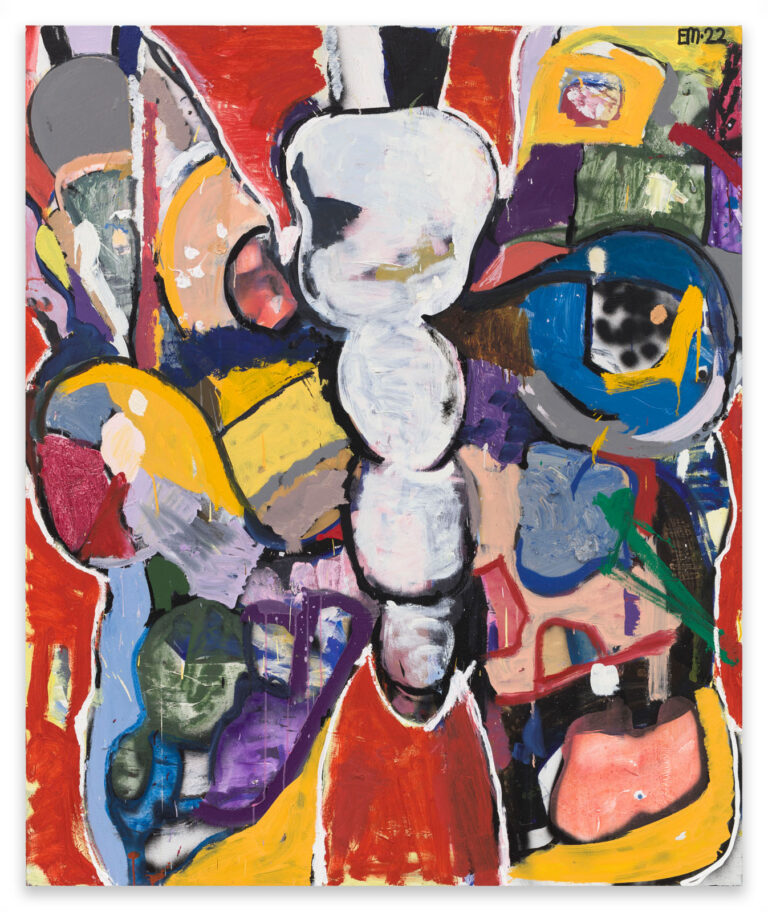

In Supernature, Raid itself becomes a ghostly insect, or a soldier behind a gas mask, standing among Martinez’s signature still lifes filled with toxic cartoon flowers and bulbous mushrooms. And this supernature is equally reminiscent of something, of the graphically cool flower forms of Christopher Wool or Carroll Dunham, of Audrey II, the carnivorous flower from The Little Shop of Horrors, of the fragile, hypersensitive lines of Matisse’s floral still lifes. With paint streaming from the nozzle, Martinez makes the Raid figure scream or howl like a siren through just a few boldly placed gestures and strokes.

Courtesy the artist and Capitain Petzel, Berlin. Ph: JSP ART Photography

Martinez’s semi-abstract scenarios have an incredible narrative energy, although this never becomes constrictive or authoritative; on the contrary, it creates a nonverbal, completely open painterly space that always reflects not only life but also painting and the history of painting. This results in the constant formation of abstract, reduced objects and symbols to which the artist repeatedly returns in his works over the years, like mandalas or the breath in meditation: tennis balls, flowers, or his gridded, cube-shaped “blockheads,” which in his words arose from “probably looking at Guston and Picasso too much when I was younger. It sort of came out of a vision I had of a Picassoid face emerging out of a Guston-type brick wall. Then it became a totemic thing. And a form to make paintings around.”

The expressive butterflies in Martinez’s Bufly series are similarly abstract, formal compositional elements; at the same time, they are steeped in spirituality and dying, childhood, C.G. Jung’s archetypes and Jackson Pollock’s totemism. In the Raid paintings, the spray can that has featured in Martinez’s paintings since his beginnings demonstrate the complex interpenetration of life and art is in these reduced forms. It becomes a symbol of artistic creation and destruction, marking, crossing out, revision, revolution, e!acement. The finger on the nozzle also represents a radical decision to take life, to finish off the enemy—whether this is a population of wasps or people.

Like the birth of his son, Martinez’s more recent paintings coincide with an era in which the climate crisis and a three-year pandemic have changed the world, an era in which societies are divided. A new cold war is beginning: before the last election in the United States, 15 percent of Republicans and 20 percent of Democrats agreed with the statement that their country would be significantly better o! if large numbers of the opposing party “just died.”

Courtesy the artist and Capitain Petzel, Berlin. Ph: JSP ART Photography

Martinez’s work is thus rooted in post-war modernism—a time in which the world still revolved around authority and people, despite the Holocaust and the atomic bomb. However, as a continuation and extension of the abstract language of the twentieth century, his paintings radically engage with the present. They speak to an era that contemplates whether human civilization will soon depart the geological world once again, and whether there is a way of thinking, a consciousness on the part of bees, foxes, trees or stones that exists entirely without us, our ego or the Enlightenment.

Martinez’s paintings, which repeatedly integrate sections of old canvases, debris, and found objects from the studio, almost always resemble collages or assemblages. You can even think of them as time capsules or time machines. “I think the whole thing of being able to transcend time with collage is amazing,” says Martinez. “I can have a painting from 2023 with a collaged element from a painting from 2007 glued on it, that’s pretty cool. It allows a longer story to be told.”

And in Martinez’s work, this story is told without hierarchies, without the pathos or heroic aspect of post-war modernism. Everything from the artist’s life can flow into his paintings, nothing is too big, too banal, too delicate, too embarrassing. He succeeds in building on the legacy of Willem de Kooning, Robert Rauschenberg, or Jean-Michel Basquiat, in making truly great paintings without having to make painting great again. Martinez’s paintings are so strong precisely because they don’t reclaim anything, they incorporate it. What is especially touching about Martinez’s animistic cosmos is the empathy with which he juxtaposes the history of painting with raw, unmediated experiences of the declining, fragile Anthropocene, whether or not they are human in origin. An insect is squashed, a dog buried. The first snow falls, plants on a windowsill bloom, a toy is left behind in a parking lot.