The Holes in History

On Women Artists Digging in Berlin’s Past

by Carina Bukuts

Rome was built on seven hills, New York was built on three islands and Berlin was built on sand. While Rome grew out of a confederation of villages on the hills, built there because of the swampy low-lying ground, New York’s location at the mouth of the Hudson River, which feeds into the Atlantic Ocean, seemed to be a good selling point for settling there. Compared with the topographical conditions of these Western metropolises, the sandy grounds of Berlin somehow seem like an odd choice for building a city there, yet alone a capital. Despite all doubts, here we are.

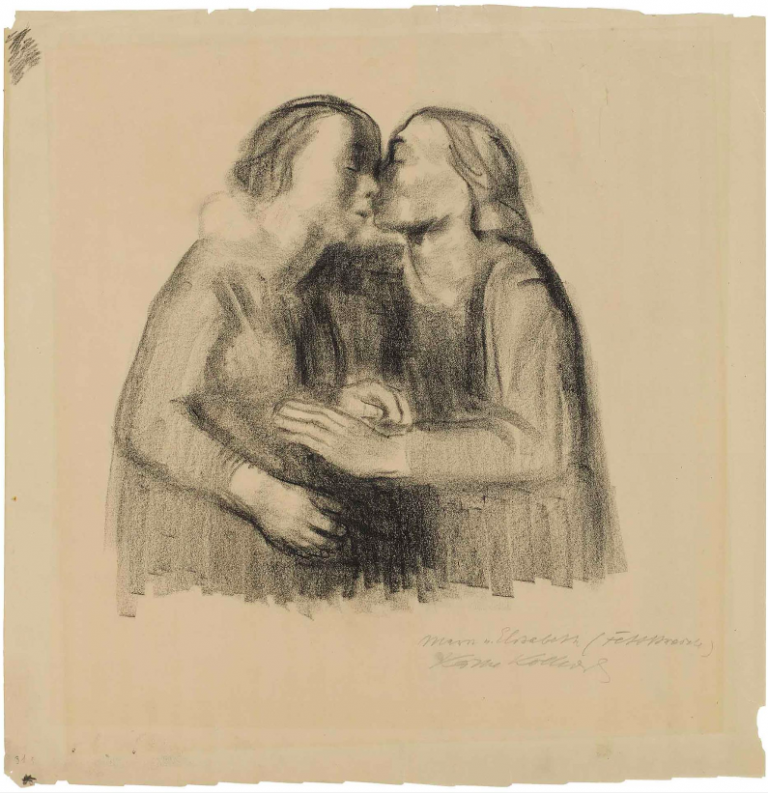

Käthe Kollwitz

Maria und Elisabeth, 1924

Courtesy Käthe Kollwitz Museum, Cologne

Even though sand is not really present in the cityscape, if you dig hole in Berlin today, you will still hit on it – but also on many more materials and objects that recall moments in history which have shaped and still define the city. Perhaps you’ll find remains of the Love Parade, which originated here in 1989, a painted concrete crumble from the Berlin Wall, a book by poet Else Lasker-Schüler which was supposed to be burned at Bebbelsplatz in 1933 or a sequin from a dress of the Roaring Twenties. If you’re an artist, you don’t necessarily need a shovel to dig a hole in Berlin.

Käthe Kollwitz didn’t need to go back in time for her work, because it was the present, she lived through that demanded being documented and portrayed: the struggle of the working class, the horror of the war and its impact on the individual, and the many ‘ordinary’ women with their needs and pains, that had never been considered subject-worthy until then. In a world pre-dominated by men, she was the first woman to be honored by the Prussian Academy of Arts and later became one of their professors. She paved the way for the many women artists who aren’t afraid to make a point, that were to follow.

Five years after the German Bundestag had decided to demolish the GDR’s Palace of the Republic on Berlin’s Museum Island in order to reconstruct the Prussian Berlin Palace, Bettina Pousttchi gave the building one last goodbye kiss. For Echo Berlin (2009/10), she covered the entire façade of the construction site (which was used as Temporäre Kunsthalle from 2008–10) with black-and-white posters that recalled Palace of the Republic’s modernist bronze-mirrored windows, designed by Heinz Graffunder. While the work wasn’t directly intended as activism against the reconstruction of the Prussian palace, it did mirror the concerns regarding it that many Berliners had – and still have. Why would a city with that much history try to rewrite its own past by getting rid of the aspects that don’t make a nice picture? In light of the planned opening of both the palace and its equally problematic museum, the Humboldt Forum, that is supposed to happen later this year, I wish Pousttchi would once again wrap up the entire building to remind Berlin of the importance of remembering our past.

Bettina Pousttchi

Echo Berlin, 2009/10

C-Print, 115 x 165 cm

Courtesy the artist and Buchmann Galerie, Berlin

Zuzanna Czebatul

Siegfried’s Departure I-III, 2018

plaster, copper, lacquer, sulfur

100 x 90 x 45 cm each

Courtesy the artist; photograph: Roman März

Now that we already touched the division of Berlin, why not take look at a figure who was perceived as mastermind of the German reunification in 1871 and then went on organize the Berlin Conference, where the greedy European empires decided which African countries they could exploit and terrorize: Otto von Bismarck. A memorial in Berlin’s Tiergarten, featuring statues of himself, Germania, Atlas, a sibyl and Siegfried, the hero of Germanic mythology, reminds of his ‘achievements’. For her sculpture, Siegfried’s Departure I-III (2018), Zuzanna Czebatul made three plaster casts that reference the right foot from Siegfried’s statue on the memorial. Each coated in different materials and patina, including copper, lacquer and sulfur, the individual pieces emphasize the passing of time and the care that goes into the maintenance of monuments. With memorials all over the world currently being questioned, dismantled and even demolished, Czebatul’s sculpture not only emphasizes the seemingly unique materiality of monuments but also stresses which historical figures are paid tribute to and who are left out.

Carina Bukuts is assistant editor of frieze magazine and editor-in-chief of PASSE-AVANT. She lives in Berlin, Germany.