Gallery Portrait

Galerie Buchholz

Philipp Hindahl, 2023

When the young art dealer Daniel Buchholz agreed to show works by a young photographer named Wolfgang Tillmans in 1993, he was already at the heart of the art world. Buchholz started his trajectory as an apprentice in Walter König’s bookshop in Cologne at age sixteen, a role that gave him a speedy introduction to contemporary art. After that, he moved to New York, which at the time was a feast for the eyes and intellect. An impactful time of his life, he would later recall.

Buchholz hails from Cologne, where his father ran an antiquarian bookshop, and upon his return from New York, he decided to open a gallery in his hometown. He moved shop several times, and photos of that time display the convivial atmosphere and density of art world celebrities and critical heavyweights who stopped by. When Buchholz speaks about these years, he condenses his story, quickly jumping between names of colleagues and collaborators.

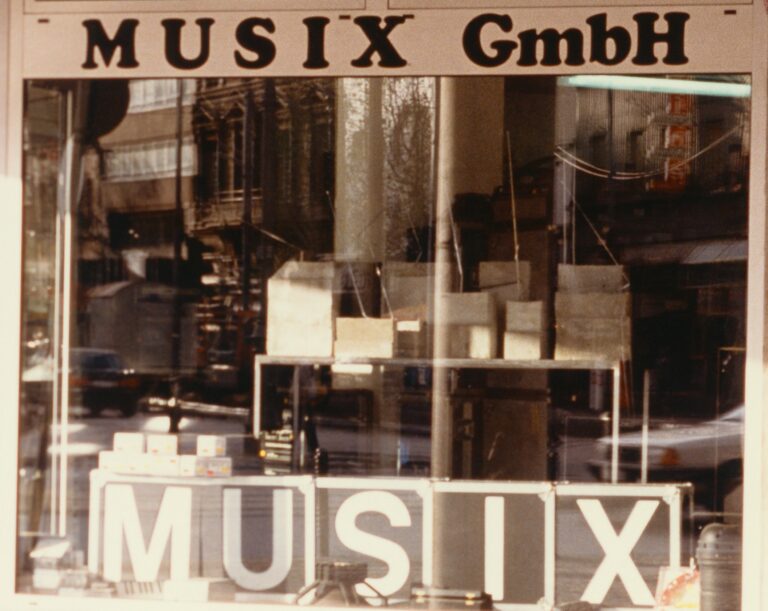

Isa Genzken, Weltempfänger, installation view. Musix GmbH, Köln 1987

Isa Genzken was among the first artists Buchholz exhibited, in 1987. Her studio at the time was close to the gallery, and after Buchholz met her, he asked if she wanted to show with him. The artist agreed to a project—“she wanted to test me first,” says Buchholz—in a music store across the gallery, where the artist set up pieces from her series Weltempfänger: radio-sized concrete blocks from which antennas protruded. Buchholz was in his early twenties then and Genzken showed solo in the gallery the following year. She has stayed with him ever since. A couple of years later, in 1993, a space behind his father’s bookstore turned into the new headquarters of the gallery. “That’s where the server is located,” he says.

Wolfgang Tillmans, installation view. Buchholz + Buchholz, Köln 1993

Isa Genzken, Neue Arbeiten, installation view. Galerie Daniel Buchholz, Köln 1994

The Rhineland has been a special place for contemporary art since the 1960s. The connection to the USA was strong, and collectors with family money, adventurous young gallerists and forward-thinking educators created an environment for contemporary art before anybody had even thought of Berlin. Eventually, in the 90s, the way dealers and curators perceived cultural production changed. Disciplines were not segregated anymore. Fashion, art, pop, and literature overlapped in productive ways.

A friend showed Buchholz photos featured in the British fashion magazine i-D, a leading cultural force at the time, and suggested he’d exhibit something along those lines. The young art dealer liked the idea. The name of the photographer was Wolfgang Tillmans, who lived in London at the time. Soon after, Tillmans visited and showed him his work, bringing prints in a suitcase, among them Lutz & Alex sitting in the trees (1992). They agreed to organize a show together. The installation, which originally occupied a space of nine square meters, would later be replicated like a time capsule at Museum Brandhorst in Munich. Tillmans is represented by the gallery to this day.

Later in the 1990s, the art historian Christopher Müller joined the gallery, initially organizing exhibitions and film screenings. Around the turn of the century, he became a partner. “My name is on the door,” says Buchholz, “but content-wise, we run this together.”

Henrik Olesen, Sexuelle Zwischenstadien—Einführung in die Theorie der Homosexualität, installation view. Galerie Daniel Buchholz, Köln 2002

Tony Conrad, Yellow Movies, installation view. Galerie Daniel Buchholz, Köln 2006

In the lead-up to the millennium, Berlin became a hub for artistic production. In 2008, Buchholz opened a branch in the capital, but he resisted the maximalism that some other recent Berlin transplants adopted with the plentitude of open space at hand: “A space too big doesn’t suit me. I’m not interested in making it huge—it’s not timely anyway.” He picked a space with hardwood floors in Fasanenstraße, which was a decidedly unfashionable choice at the time. But it made sense because a few years late other galleries would flock to the former West. The neighborhoodhad been considered stuffy and bourgeois for the longest time.

Despite preconceptions, the rich tradition of this area increasingly comes into focus. The road that traverses Charlottenburg and Wilmersdorf, with its grand 19th-century houses and lush greenery, has been home to the pre-war art world. The dealer Alfred Flechtheim, who championed the avant-garde of the Weimar Republic, kept a vast apartment in the area, before he had to flee persecution from the Nazis. Auction houses still reside in the formerwestern part, and the Literaturhaus hosts readings and symposiums.

In 2015, the gallery opened a new branch in New York’s Upper East Side— yet another unpopular choice for an art space. But it’s one block away from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. On the same street, the gallery opened the Betty Center, which holds the estate of the American artist Lutz Bacher—also represented by the gallery—who declared her archive an artwork in itself.

Currently, the gallery is invested in cataloging the work of Isa Genzken, who has a retrospective coming up at Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin. Archival work may not be an immediately profitable endeavor, but it provides a valuable base for art historical research. Buchholz counts this among the indispensable responsibilities of a gallery.

It is impossible to not read the gallery’s roots in the 1990s as a starting point for today’s program. A roster that includes artists like Anne Imhof, who incorporates fashion, art, and music, or the young painter Samuel Hindolo, who is showing at Gallery Weekend this year, attest to openness and intellectual flexibility. “Our program keeps growing, because we try to stay interested in what is going on,” says Buchholz. “We don’t want to represent only one generation.” The gallery continues to counsel artists on different matters, whether it is about the work itself, or if they need help finding a studio. Buchholz: “We provide a place to go, an infrastructure.”