Jay Chung & Q Takeki Maeda

Mongoloid

2. The Mongoloid myth

As a species, we have always been obsessed with how we look and in which ways we appear to be similar or different from one another. The ancient Hindu caste system and the apartheid system of South Africa were just two of many systems based on our perceptions of caste, tribe and race. Even before the Portuguese first set foot in Japan in 1542, Europeans were trying to come to grips with the human phenotypical diversity which they observed in the peoples whom they met on their voyages across the seas. Today we understand that in scientific terms, there is actually no such thing as race (Cavalli-Sforza et al. 1994). We are all members of one large human family. The relationship between genes, their phenotypical expression and their pleiotropic interplay is inordinately complex, and our individual differences often tend to be larger than the differences between groups.

Historically, long before the discovery of the molecular mechanisms underlying genetics, scholars resorted to superficial classifications in their attempts to understand human diversity. Classification was con- ducted on the basis of somatology, which involved crude observations about external appearance. In 1758, in the famous tenth edition of his Systema Naturæ, Carl Linnæus distinguished between four geo- graphical subspecies of Homo sapiens, i.e. europaeus, afer, asiaticus and americanus. Later, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, in a dissertation which he defended at Göttingen in 1775, distinguished between what he imagined were five human races, namely the ‘white’ Caucasiae, the ‘yellow’ Mongolicae, the ‘black’ Aethiopicae, the ‘red’ Americanae and the ‘brown’ Malaicae (1776 [1795]: xxiii, xxiv). With his coinages, Blumenbach single-handedly invented the ‘Mongoloid’ and ‘Cauca- soid’ races. With regard to his Varietas Caucasia, Blumenbach opined:

The name of this variety is taken from the Caucasus mountains, as well as, indeed, most of the southern flank thereof, in the Georgian area, where the most beautiful race of men is to be found and in whom all the physiological reasons converge so that it may be presumed that the first human beings are likely to have been native to this region.

(1795/1776: 303)1

Later, Johann Christian Erxleben recognised four of the same races as Blumenbach but under different names, with his Homo sapiens europaeus, asiaticus, afer and americanus (1777: 1, 2) corresponding to Blumenbach’s Varietas Caucasia, Mongolica, Aethiopica and Americana (1795 [1776]: 304, 307, 310, 319) respectively. As opposed to Blumenbach’s Varietas Malaica, Erxleben distinguished no separate Malay race, but he made finer distinctions in northern Asia, distinguishing a more northerly Homo sapiens tatarus from the Chinese phenotype, which he termed Homo sapiens asiaticus, and he grouped Lapps, Samoyeds and other Uralic peoples under a distinct heading named Homo sapiens lappo. In France in 1801, Julien-Joseph Virey basically followed Blumenbach in recognising five races, but he outdid Erxleben in his attempts further to subclassify within these races.

Taking his inspiration from Blumenbach, the German scholar Christoph Meiners (1747–1810), on the basis of the descriptions in Dutch and Russian accounts of the peoples encountered in other parts of the world, set up a classification of races based on what he imagined where the uralte Stammvölker or racial prototypes of mankind. His cogitations were published posthumously in three volumes. In the second volume, der alte Mongolische Stamm or ‘the Mongoloid race’ was designated by Meiners as one of the main races of mankind. He wrote:

In physiognomy and physique, the Mongol diverges as much from the usual form as does the Negro. If any nation merits being rec- ognised as a racial prototype, then it should rightfully be the Mon- gol, who differs so markedly from all other Asian peoples in his physical and moral nature.

(1813, 2: 61)3

Meiners described the cruelty of the invading hordes led by Genghis Khan as being inherent to the ‘moral nature’ of the Mongoloid race, conveniently overlooking the historically well-documented cruelties of Western and other peoples. The serendipity of the nomenclatural choices made by Blumenbach (1795 [1776]) and Meiners (1813) gave rise to the Mongoloid myth. If the Mongols were the primordial tribe from which all peoples of the Mongoloid race descended, then it was logical to think that the homeland of all Mongoloids lay in Mongolia.

Jean Baptiste Bory de Saint-Vincent (1825: 323–325) subsequently introduced the term Homo sapiens sinicus for the Chinese, who he thought distinct from proper Mongoloids, but the ‘Chinese race’ would later vanish from subsequent classificatory schemes because the Chinese came to be seen by such early physical anthropologists as a mixture of the Northeast Asian ‘Tungids’ and the ‘Palaeomongoloids’ of the Himalayas and Southeast Asia.

I have often been told by people in Nepal and northeastern India that their ancestors came from Mongolia. Some even adorn their lor- ries, cars and motorcycles with captions like ‘Mongol’ or ‘Mongolian’. When I ask them why they think so, they tell me that they are members of the Mongoloid race or मंगोल जाित Maṅgol jāti, which, as the name tells us, must have originated in Mongolia. I do not have the heart to tell them that the very idea was dreamt up by a German scholar in Göttingen in the early 1770s, who was just imaginatively trying to make sense of human diversity, though he had no expertise or specialist knowledge to do so.

People in the West suffer from the same obsolete ideas. A friend of mine from Abkhazia, who happens to be a renowned linguist, was travelling in the United States of America with a colleague of his from the Republic of Georgia. Whilst driving a rented car, they were pulled over by a police officer. The obese and heavily armed man in uni- form demanded to see my friend’s driving licence and then asked them, ‘Are you folks Arabs?’ The policeman spoke with a heavy American accent and pronounced the word Arabs as [ˈeɪræːbz]. Since Abkhazia and Georgia both lie in the Caucasus, my friend responded, ‘No, Sir, we are both Caucasians’. This response somehow displeased the police officer, who asserted, ‘I am a Caucasian!’. My friend coolly responded, ‘No, Sir, you are not a Caucasian, and you do not look particularly like a Caucasian. We are Caucasians.’ The exasperated policeman spluttered, ‘. . . but . . . but I am white!’

Excerpt from: George van Driem, The Eastern Himalaya and the Mongoloid myth, 2018

Installation view, Jay Chung & Q Takeki Maeda, Mongoloid, Eden Eden, September 2021

Wu Tsang

Lovesong

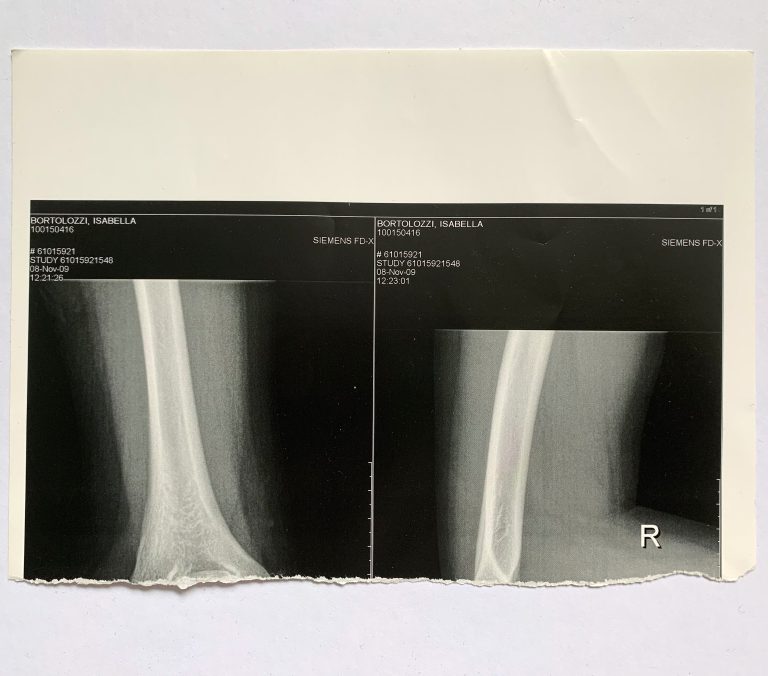

Wu Tsang, Liebeslied (with Tapiwa). Courtesy the artist and Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin; Photo: Graysc.

Wu Tsang, Anthem, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin; Photo: Graysc.

Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi is pleased to present a staging of Anthem, a multi-channel sound

installation and sculptural projection featuring the legendary singer, composer, and transgender activist Beverly-Glenn Copeland.

Originally commissioned for the Guggenheim’s Rotunda space, Anthem draws from lesser-known histories of the word, which are tied to practices of spiritual call-and-response. The film portrait of Glenn-Copeland becomes a polyphonic collaboration woven with contributions from his partner Elizabeth Glenn-Copeland, musician Kelsey Lu, composer Asma Maroof, and performer Tosh Basco.

Wu Tsang, Anthem, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin; Photo: Graysc.

Wu Tsang, Anthem, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin; Photo: Graysc.

Anthem highlights the central role that collaboration plays in Wu Tsang’s practice, exemplifying how she utilises it as an aesthetic strategy for undoing conventional narratives and modes of authorship. Tsang frequently works with a “roving band” of interdisciplinary artists called Moved by the Motion, cofounded in 2016 with Tosh Basco.

As an independent recording artist, Glenn-Copeland’s career spans over 50 years. He is most well known for his pioneering experimentations in electronic music, which were ‘rediscovered’ in 2015 with the cassette tape Keyboard Fantasies (1986), now a cult classic.

Wu Tsang, ♾, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin; Photo: Graysc.

ANTHEM (2021)

A FILM BY WU TSANG

IN COLLABORATION WITH BEVERLY GLENN-COPELAND

Featuring Beverly Glenn-Copeland and Elizabeth Glenn-Copeland

Musical Accompaniment by Kelsey Lu

Arranged by Asma Maroof and Daniel Pineda

Movement Direction by Tosh Basco

Directed by Wu Tsang

Produced by Tosh Basco

Produced by Jason Levangie and Mark Tetreault

Executive Producers: David Codikow and Nadja Rangel

Director of Photography: Paul McCurdy

1st Assistant Camera: Riley Turner

2nd Assistant Camera: Jacob MacDougall

B Camera Operator/DMT: Tim Mombourquette

Gaffer: Mark Kenny

Grips/LX: Stuart Rankin and Dave Hutchins

Art Director: Michael Pierson

Costumes: Peter Do

Styling: Kyle Luu

Wardrobe Assistant: Sarah Haydon Roy

Makeup: Charlotte Gavaris

Hair: Mallory Glenn

Production Assistant: Pierre Hache

Driver: Izzy Muschol

Catering: Lisa Barry and Courtnay MacMullin

Sound Recordist: Francisco Lopes

Editor: Wu Tsang

Sound Mixer: John Herberman

Sound Design: Asma Maroof and Daniel Pineda

Sound Spatialization: Cy X and Dave Rife

Colorist: Randy Coonfield

Post Production: Blueline Finishing

Special thanks:

X Zhu-Nowell, Liyu Yeo, Ellen Kirk, Nick O’Byrne, Lookout Kid Records, Third Side Publishing, Ship’s Company Theater, James Early, Posy Dixon, Lucie Rebeyrol, and Fred Moten

Wu Tsang, ♾, 2021. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin; Photo: Graysc.